New Zealand Artists

Shane Cotton (born 1964)

Lives and works in Palmerston North, New Zealand

Shane Cotton is of European, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Hine, and Te Uri Taniwha descent. His work draws on his Māori and European heritages, combining popular culture, art-historical references, and significant histories of New Zealand.

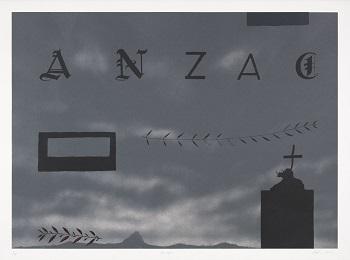

The rich and velvety landscape upon which text and symbols float is based on a photograph Cotton had seen of the Gallipoli peninsula, with geographical features exaggerated and fictionalised. The pedestal surmounted by turf and a grave cross is another image inspired by a photograph from Gallipoli, and the artist intended to evoke a sense of displacement for the Australian and New Zealand soldiers who landed there. Cotton wanted the work to be simultaneously an image of contemplation and a meditation on remembrance:

“For me, it’s become a study in remembrance, and what it means to do it, and the process of doing it – that we can reflect on the narratives and the stories, and around the commemoration and what it means for us personally.”

The branches that float through the sky reference wreaths: in Māori culture a head wreath (pare kawakawa) is a symbol of grief and mourning. Here they reference the grief Australia and New Zealand shared during and after the First World War.

Brett Graham (born 1967)

Lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand

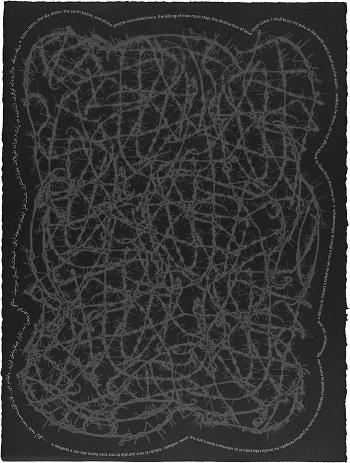

With emphasis on detail and surface, Brett Graham engages a dual dialogue of Māori and European histories. In the Australian War Memorial’s First World War Galleries, Graham encountered a knot of Turkish barbed wire cut to pieces by shell-fire in Gallipoli. For Graham the barbed wire represents a dual history: a battle on foreign soil, and the experience of his Māori ancestors interned in New Zealand when they refused to go to war.

In total, 2,688 Māori and 346 Pacific Islanders served with New Zealand forces during the First World War. This was the first major conflict where Māori served as part of New Zealand’s army. As enrolment numbers slowed, there was a strong push for men from the Waikato and Taranaki tribes, who had not supported the war, to enlist. Their refusal led to government-imposed conscription, and men who did not report for training when balloted in 1918 were imprisoned.

Here, text printed in English, Māori, and Ottoman Turkish is taken from the words of the Waikato tribe’s King Tāwhiao, quoted by his granddaughter in resistance to New Zealand’s participation in the War:

“Listen, listen, the sky above, the earth below, and all the people assembled here. The killing of men must stop; the destruction of land must stop.

I shall bury my patu [club] in the earth and it shall not rise again … Waikato, lie down. Do not allow blood to flow from this time on.”

Fiona Jack (born 1974)

Lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand

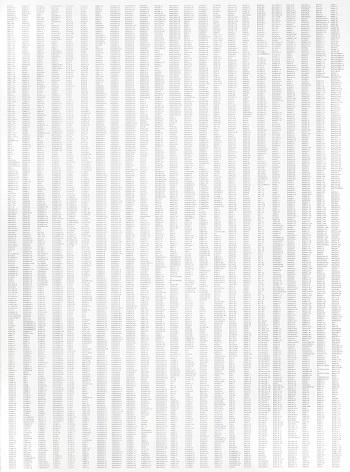

Based in Auckland, Fiona Jack works across a range of media, undertaking archival research and collaborating with various communities around New Zealand to examine social histories. The prints in this portfolio were commissioned as an edition of 20; however each of Jack’s prints is a unique print. Stretching across a white expanse of 20 sheets is a survivors’ roll of honour.

When thinking about family stories from both the First and Second World Wars Jack realised that “in our large extended family everyone known to me survived”. Growing up she had not recognised the significance of this or appreciated it as a blessing. Tales of traumatised and damaged people returning home carried an emotional weight, and Jack was conscious that while “they hadn’t made the ‘ultimate sacrifice’ their experience was beyond anything I could imagine … yet none of them were on any national roll of honour”. In contrast to Australia, it was unusual for the names of First World War survivors to be listed on New Zealand memorials, and there was no complete list of those who served and survived.

While it may appear to be a simple list, this singularly exhaustive roll of New Zealanders who fought in and survived the war was painstakingly assembled by Jack in collaboration with historian Phil Lascelles. It remains “the first and most complete list” of New Zealand First World War survivors to date, comprising 108,920 names compiled from original embarkation lists.

John Reynolds (born 1956)

Lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand

John Reynolds is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated contemporary painters and printmakers. Engaging literary, religious, art-historical, and architectural references, his text-based works often allude to New Zealand’s cultural identity and its formation from complex histories, ideas, and moral values.

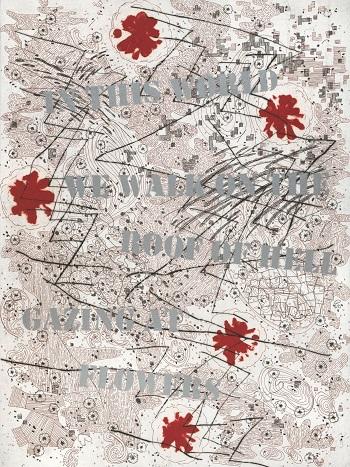

Reynolds was interested in fictionalised accounts of military history and conflict rather than in direct historical accounts of theatres of war. This influenced Reynolds’s print to be more interpretive and formally driven rather than descriptive of a particular event or moment. For Reynolds “the human experience from 100 years ago is very unknowable”; later generations will never have a clear understanding of both the banalities and the terrors of the First World War.

Here he presents a haiku by Japanese poet Issa:

“In this world

we walk on the roof of hell

gazing at flowers”

The terrain of war beneath the haiku is made of a rich “kimono fabric” of camouflage and Ottoman motifs, red splashes, and violent zigzagged gashes.

Sriwhana Spong (born 1979)

Lives and works in Berlin, Germany

Sriwhana Spong is of New Zealand and Indonesian heritage. In her practice she explores the way art can draw upon fragments from history to re-imagine a past event or performance.

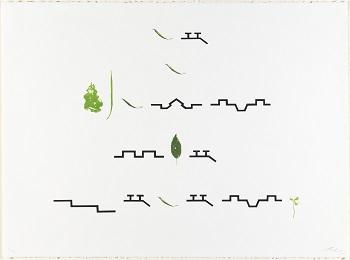

Spong has devised a private alphabet using abstracted trench designs drawn from First World War maps, along with facsimiles of leaves collected by the artist in Belgium. The idea for an alphabet, or code, emerged from the artist’s sense of her own inability to speak about the horror of war. This language of pictorial symbols plays on the “code” as a form of opaque communication and a tool for the dissemination of secrets.

The translated text appeared in an official letter sent to a soldier’s family, advising them of his death. Found by Spong at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium, it stated he had died “at a place not stated”. Brief and impersonal, these five words capture the tragedy of a person dying in a foreign land, for both the deceased and their loved ones.

The trench designs are, like code, a hidden structure; a subterranean architecture that speaks of the hardship endured by soldiers. The fragile leaves were gathered by the artist in Belgium, and copied by hand onto lithographic stone. They reference trees currently growing in soil enriched by the dead; a re-materialisation of what has passed into new forms.