Von Braun’s earlier space shots

Long, sleek and aerodynamic, the rocket was the product of Wernher Von Braun’s dedicated research and leadership over some 15 years. Costing hundreds of millions, it was liquid fuelled, consuming 126kg of alcohol and liquid oxygen per second and emitting an ear-piercing scream when it left its launch site. The fuel lasted for up to 70 seconds, by which time the craft was travelling at 1341 meters per second and was on the verge of leaving earth’s lower atmosphere. Fuel expended, the rocket was still subject to Earth’s gravity however, and now entered a parabolic trajectory, arching down towards a target zone some 350 kms away.

But unlike Von Braun’s Saturn V which propelled the Apollo 11 mission on its way to the moon, this rocket had a more sinister purpose, and the landing place was not an empty tract of wilderness. The target zone instead was London or Antwerp, and the aim was to wreak vengeance on the enemy. The rocket was the Vergeltungswaffe 2, known to history as the V2.

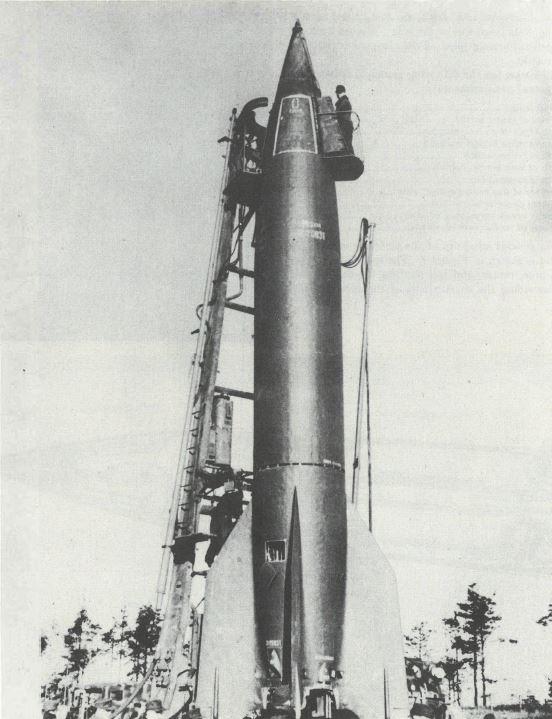

A V2 being prepared for launch

Germany in the 1930s was a world leader in many areas of applied physics, jet propulsion, engineering, aerodynamics and in the science of ballistics. The young Von Braun, brilliant, charismatic and highly practical, shone amongst his peers. A member of rocket clubs from an early age, his stated dream was to reach for the stars, and to see humanity travel to space.

But in the murky world of 1930s Nazi Germany, his clear ability aligned all too well with the darker ambitions of the German army for a weapon that would replace conventional artillery, travelling further and carrying a greater explosive yield than any artillery shell.

Initially he and his team worked in testing grounds near Berlin, but the need for secrecy led them to seek more remote testing grounds. Such an area was found on the northern coast at Peenemunde. Heavily forested and a haven for wildlife, Peenemunde quickly became the world’s first rocket test centre, staffed by leaders in their fields, well paid and with the best equipment that money could buy. As with NASA’s Cape Canaveral, it was also fronted with ocean, but unlike NASA’s facility, at Peenemunde secrecy was paramount, and enormous effort was made to keep the site safe from prying eyes.

Launch of a V2 from Peenemunde

Three prototype models of the rocket were produced prior to the development of the V2. On October 3 1942 Von Braun’s efforts paid off, with the first successful launch of a V2 rocket. The rocket was 14 metres long, and weighed 12.5 tonnes, 70% of which was fuel. It was guided by an advanced gyroscopic system that sent signals to aerodynamic steering tabs on the fins and vanes in the exhaust. An electronic device measured the acceleration of the rocket, and shut off the motor at a calculated point to allow the rocket to reach the target on a ballistic trajectory.

Inside one of the control compartments of the Australian War Memorial's V2

A sectional drawing of the V2 showing its combustion chamber and fuel tanks

The combustion chamber generated about 55,000 lbs (25,000 kg) of thrust on launch, which increased to 160,000 lbs (72,000 kg) when the maximum speed was reached.

Design work on the V2 helped inform the later development of Space rocket engines. This shows the V2’s combustion chamber and fuel feed arrangement.

It took until 1944 before V2s could be manufactured, delivered and launched reliably. Much of the manufacture was undertaken in a vast underground factory in the Harz Mountains, by thousands of malnourished, brutalised inmates from a nearby concentration camp. At one stage 160 workers were dying each day, with the total number of deaths thought to have reached 6000.

On 8 September 1944 the V2 campaign against Britain began. By this time, Germany was under constant day and night attack from the air, Peenemunde had been heavily bombed, and the German armies were in steady retreat from both Soviet and Western Armies. But to Hitler and his party, ‘wonder weapons’ such as the V2 could turn the tide and bring the allies to the bargaining table. The missile could be easily transported, quickly set up, and once launched was unstoppable.

Over the next 6 months 1,115 were fired against England, 1,341 against Antwerp, 65 against Brussels, 98 against Liege, 15 against Paris, 5 into Luxembourg and 11 against the Remagen bridge over the Rhine river. Many of the missiles fell into empty countryside or fell into the English Channel. But a large number nonetheless hit populated areas. The effect of such a missile strike hitting a city block could be devastating, both from the kinetic energy of the missile hitting the ground at three times the speed of sound, undermining building foundations, but also from the effect of the detonation of the explosive warhead. One V2, hitting the Rex cinema in Antwerp, killed 567 people, mainly British and US servicemen, while another, which struck a Woolworths shop at New Cross in London in November 1944, killed 168 people and injured 122 passers-by.

Almost until the surrender of Nazi Germany, research continued into improving the range and accuracy of the V2. Further developments in train involved placing small wings on the rocket to increase the gliding range on descent, and a 26 meter long giant two-stage rocket, code-named A-10, with an expected range of 2900 to 4000 km. Preliminary calculations were carried out, but no detailed design work was undertaken.

The A-10 rocket

Although the V2 was technically brilliant, it consumed vast research and materials, and was not strategically important to the course of war. Both the Western Powers and the Soviets appreciated, however, that they needed to understand how the rocket functioned, and whether they could use it. Almost as soon as the respective armies pushed into Germany, this process began, with the collection of scientists and the re-building of rocket parts. Testing and launching soon followed, and continued in the USA during the late 1940s. The first animals sent into space were passengers on board modified V2s, and the first photographs from space, showing the now familiar curvature of the earth were also taken with V2s.

One of the rockets reassembled by the British after the fall of Nazi Germany made its way to Australia in 1946. After being stored at the Weapons Research Establishment in South Australia it was transferred to Australian War Memorial in 1958.

The Australian War Memorial’s V2 rocket

The Australian War Memorial’s V2 combustion chamber

It doesn’t look so terrifying now. Lying on its transport trailer, with faded paint, and dimpled wrinkled skin, and missing some of its outer panels, the rocket is a technical curiosity from the pre-internet age. But as we remember and commemorate the excitement of the 1969 moon shot, it is pertinent to remember humanity’s earlier travel through the lower reaches of space.