The Red Falcon

The death of Baron von Richthofen

Watercolour with pencil and charcoal on paper

A Henry Fullwood, 1918

ART02495

Loved and lauded by his German countrymen; reviled, feared and admired by his enemies, Baron Manfred von Richthofen was the First World War’s most prolific ace, shooting down 80 Allied aircraft until he was himself brought down and killed on 21 April 1918. Already infamous to the Allies as ‘the red devil’ or the ‘red falcon’, his name and exploits have become synonymous with the air war fought over the Western Front, while his aircraft, a Fokker Dr1 Triplane is instantly recognisable, and has been the oft-reproduced subject of models, flying replicas and cartoons.

During the course of Von Richthofen’s last flight, his progress was observed by numerous parties on the ground, and almost immediately his aircraft crashed, observers of the fight and the crash swiftly secured the aircraft and removed the Baron’s body. He was recognised as ‘a great airman and a clean fighter’, and buried the next day with full military honours by 3 Squadron Australian Flying Corps, with the proceedings being recorded in footage now preserved by the Australian War Memorial.

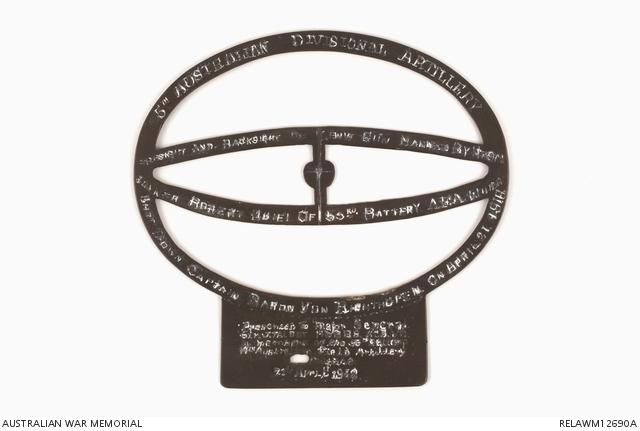

Almost as quickly, controversy erupted as to who and what had brought the ‘red falcon’ down – fire from various Australian troops on the ground, each of whom claimed to have fired the fatal shots, or from the Canadian pilot ‘Roy’ Brown, who had been chasing the Baron’s aircraft. So certain was one Australian machine gunner , Robert Buie, of his claim, that he inscribed his Lewis gun foresight with the details of his success, and presented it to Sir Talbot Hobbs, commanding the Australian 5th Division.

Anti-aircraft Foresight for a Lewis machine gun, made and used by gunner Robert Buie of the 53rd battery, 5th Australian Division Artillery in France. Scratched onto the sight is the inscription: '5th Australian Divisional Artillery. Foresight and backsight of Lewis gun made by No3801 Gunner Robert Buie of 55th Battery A.F. A. which shot down Captain Baron Von Richthofen on April 21 1918. Presented to Major General Sir Talbot Hobbs KCB VD by members of the 55th Battery 14th Australian Field artillery [illegible] 21st April 1918'

The Baron’s red aircraft was set upon by soldier sightseers, eager to secure a souvenir. The aircraft’s large German national crosses were much prized, and quickly cut from the aircraft’s twisted wreckage, while the joystick and smaller instruments were also detached and spirited away. Especially sought after were scraps of red-painted linen fabric and wing strut, which were cut into pocketable chunks. Even the Barons’s overalls were cut into fragments, some of which were sent home to relatives in Australia.

Painted German cross on wing fabric : Baron Manfred von Richthofen, Geschwader 1, German Air Service.

Red painted piece of Fokker wing strut : Baron Manfred von Richthofen, Geschwader 1, German Air Service.

Some of these objects were collected by the fore-runner of the Australian War Memorial, the Australian War Records Section, and have been part of the Australian National Collection for nearly one hundred years. Other fragments were donated only in more recent times, by the servicemen who collected them or by their relatives. Detailed analysis of the fragments still has the potential to reveal much information to future researchers. The propeller fragments, for instance, when taken as a collection, reveal the aerodynamic profile of the blade, the timber species used, the number of laminations in the blade, the glue used, and the manufacturer. Other artifacts have the potential to reveal the precise alloys used in engine components, plywood structural manufacturing techniques, raw materials used in the fabric, pigmentation of paint, and strength of components.

Part of the propeller from Fokker Dr I : Baron Manfred von Richthofen, Geschwader 1, German Air Service.

The collection can be read on another level however; as a mute testament to the career and death of Manfred von Richthofen, but also to his foes and to the men who carefully squirrelled away precious fragments of his triplane. It is also uplifting to appreciate that although Von Richtofhen had been directly responsible for the deaths of a large number of Allied airmen, his death one hundred years ago was met not just with satisfaction that a dangerous enemy had been removed from the air, but also with mingled regret at the death of a gallant airman.

Control column from a Fokker Dr I aircraft, serial No 425/17. Baron M von Richthofen, Geschwader 1, German Air Service.

RELAWM00704