The Not So Great Escape

On the 19th November 1941, Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney II was lost, with all hands, off the coast of Western Australia after engaging with the German raider HSK Kormoran. The discovery in March 2008 of the final resting place of the Sydney and the Kormoran attracted much attention. Understandably, there has been much discussion over the circumstances surrounding the loss of the Sydney; however the story of the Kormoran’s Commander, Theodor Anton Detmers, and that of his crew, continued long after the battle. Almost a week after the sinking of the Kormoran, Detmers was picked up in a lifeboat along with other crewmen. Brought to Australia as a prisoner of war, he and several of his countrymen were detained in Dhurringile Prison Camp, Victoria. It was not long before the Commander and his countrymen had formulated a plan to escape their fortress using a hand-drawn map of Australia’s east coast, now held by the Australian War Memorial.

Group portrait of German Officer prisoners of war (POWs) interned at Dhurringile. Detmers is in the front row, third from left. 030185/05

Dhurringile Prison Camp had been established when military authorities took over Dhurringile Homestead. Isolated and vacant, it had been commandeered to house German Officers.

Conditions for tunnelling were apparently favourable as escape plans at the camp had been attempted before. Such was the zeal of the prisoners that inspection trapdoors had been constructed in the floors of all ground-level rooms. Merely one room lacked this precaution, a tiny room containing a crockery cupboard. The prisoners had an idea to lift some of the floorboards and slide down between the cupboard and the wall.

By the turn of 1945 a new tunnel had been designed and engineered by the prisoners using what they could muster, be it fashioning a crude compass or utilising the water level in a garden hose. Their plans were rather sophisticated as they knew from experience not to build the tunnel entry close to the hole in the floorboards lest it be discovered. They fashioned air ducts out of water pipe joined by jam tins, creating air flow using a hand bellows and a beer-pump from the canteen. The tunnel was dug and passed forty meters beyond the security wire, past the spot where listening devices had previously been laid by guards in order to detect digging. While tunnelling was taking place there were some close calls and on the odd occasion workers had to be temporarily left in the tunnel while those up top concealed the entrance from suspicious guards. In all, it had took six months to construct by twenty prisoners.

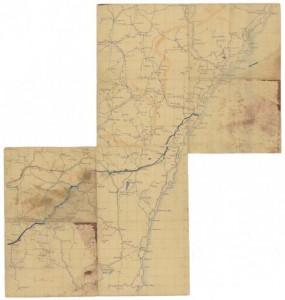

Once the tunnel had been completed, however, they still had to escape and make their way across the country undetected. Fortunately for these prisoners, obtaining civilian clothing was relatively simple because they could make use of the plainer part of their uniforms. A handful of men possessed money, a ration of food, and hand-drawn maps. Theodor Detmers was one of those men.

Detmers was a career navy man, having joined the German navy, the Reichsmarine, in 1921. He was steadily promoted and had visited Australia back in 1933 during a training cruise. Holding senior rank in the camp, it has naturally been assumed that he was one of the masterminds of the operation.

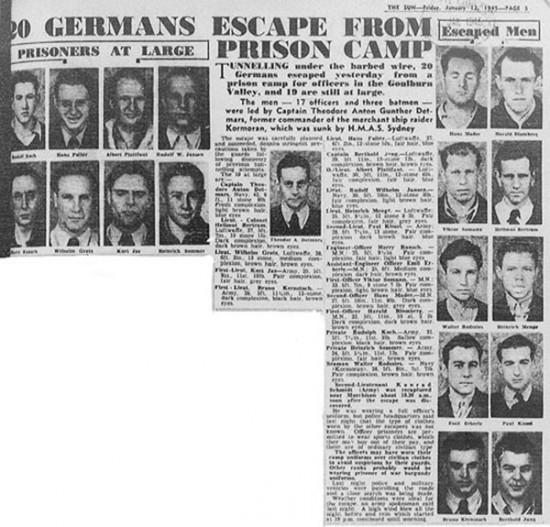

The escape was timed for the evening of Wednesday the 10th of January, 1945. On the night of the escape, Detmers had been so brazen as to ask his guard the outlook of the weather. Despite the suspicions of the guards and their attempts to thwart any escape attempt, twenty prisoners broke from the tunnel in two groups over a period of several hours. They could not have timed the weather better, implementing their plan under the disguise of a storm. Their success was not discovered until the next morning’s roll call at 7am. By then, the men had scattered across the countryside. Relevant authorities were notified and photographs and names were distributed to newspapers and police.

Road and rail were under guard by the army and police as searching continued over several days. Weather worked against the search parties, covering their tracks and the search went on with interesting results. One escapee’s train was delayed and he was subsequently apprehended as he downed a beer in a nearby pub to pass the time. Police investigated a sighting of suspicious looking characters on a golf course only to find they were a gang of local thieves, still carrying their booty. The decriptions of Detmers offered in the newspaper articles are interesting: 6ft, fresh complexion, use of double-possessive and superfluity of sibilants.

By Wednesday the 17th, only four men remained at large, including Detmers. Some of the prisoners had fled south seeking Melbourne, while others, including Detmers, had set their sights on Sydney. Detmers’ intended destination may be assumed by his possession of a hand-drawn map produced during his internment at Dhurringile. Recently donated to the Australian War Memorial, the map consists of two pieces, themselves folded into quarters. The two pieces overlap, seeming to centralise on Sydney.

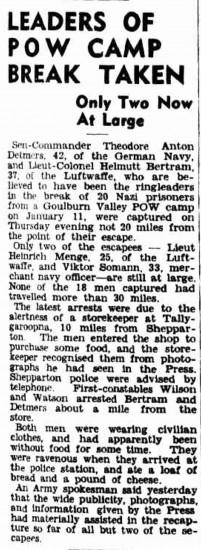

By the 18th, Detmers, with a prison mate, had progressed north to Tallygaroopna, not far from the New South Wales-Victoria border. They had been walking by night and resting during the day but when his partner injured his ankle their progress became sluggish. Their food supply dwindling, Detmers waited nearby for his companion to risk venturing into a store. The game was up when his companion was recognised by the owner. First Constables Wilson and Watson apprehended them without a struggle, for it had been a long, exhausting, dirty, hungry, hot and rainy week for the escapees. Wilson confiscated some items from them, including the map. Back at the police station, the prisoners hungrily consumed a loaf of bread and a pound of cheese.

Detmers was promoted to Captain while a prisoner of war in Australia and awarded the Knight’s Cross, a German military decoration. He remained a prisoner until after the war when he was repatriated. Although his attempt to escape was unsuccessful, it demonstrates the ingenuity which many Prisoners of War exercised in order to obtain their freedom if not cause havoc for their keepers.

References:

1. The Argus (Melbourne, VIC), Friday 12th January 1945; Saturday 13th January 1945; Wednesday 17th January, 1945; Saturday 20th January 1945.

2. Detmers, Theodor Anton. The Raider Kormoran, translated from the German by Edward Fitzgerald. (London: William Kimber, 1959).

3. The Sun (Melbourne, VIC), Friday 12th January 1945.

4. Winter, Barabara. Stalag Australia: German Prisoners of War in Australia (North Ryde: Angus and Robertson, 1986)