'I can't believe now that I was a part of it'

Owen Cook was 22 years old when he was flying Lancaster bombers over Europe during the Second World War.

“I can't believe now that I was a part of it,” he said.

“To be part of such an extraordinary event in world history that will never be repeated in the same form.

“The love of flying some remarkable aircraft. A chance to travel across Canada through the Rockies by train, to see San Francisco, New York and Niagara Falls … to travel from London to Edinburgh on the Flying Scotsman … to be able to see so much of the UK on my leave and after the war, and land in France as part of the POW repatriation flights.

“It was a lot for a young man from Melbourne in 1945.”

Now 100, he looks back at his time as a Lancaster pilot during the war as one of the most significant times in his life.

“I loved to fly, and I had a good time flying,” he said. “I never had any troubles. They’re a lovely plane to fly. They’re very docile, and you don’t have any problems; you could set them on a course, and they’d stay there all day in a circle until you moved something.

“They are just a lovely aircraft, and everybody who flew them liked them.”

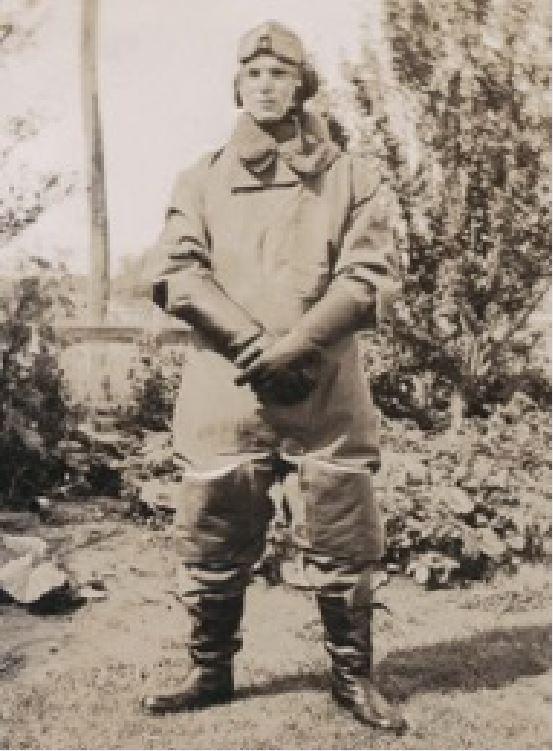

Owen Cook during the war. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

Owen Cook was born in St Kilda, Melbourne, on 27 March 1921. His father, Oswald Thomas Cook, had served on the Western Front during the First World War and his uncle, James Alonzo Cook, served on Gallipoli. Both were wounded several times during the fighting in France.

When the Second World War broke out, Owen was working as an electrical engineer with the State Electricity Commission in Victoria. It was a reserved occupation, so Owen was not allowed to enlist for active service at first. He was finally released from his position when he was 20 years old. He joined the Australian Imperial Force in May 1941, serving with the 52nd Infantry Battalion in the Ordnance Workshops at Dandenong and Puckapunyal. It was the army that suggested Owen transfer to the Royal Australian Air Force at the end of 1942. He had an aptitude for Morse Code and the Army thought the Air Force would be a good fit for him.

He was selected for pilot training and learned to fly in Tiger Moths at No. 7 Initial Flying School in Launceston, Tasmania. He remembers closely inspecting one of the planes that was being overhauled at the time.

“I wasn’t impressed with the Tiger Moth, as it looked too flimsy and too small,” he said.

“My instructor was an ex-member of a South Australian citizens’ Light Horse Regiment, and his method of instruction was a little different. He was very severe and exacting.

“The first time I went up, he flew around for about 15 minutes, said ‘I’ve had enough of this, we’re going down,’ and he flew straight down to the Esk River, flew along the river, and out the other end as fast as he could.

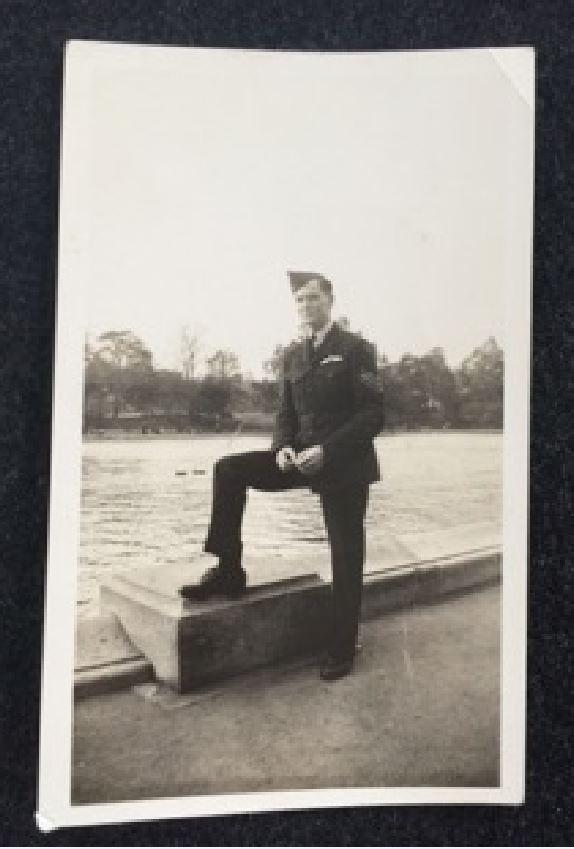

Owen Cook being given his wings. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

“I’d been taken on a half-hour orientation flight and after about 10 minutes, the Rambo-style instructor yelled into the voice tube: ‘You’re not going to go white on me, Cook?’ I yelled back, ‘No, sir, I’m fine,’ but I think I was a liar. Then he did a fighter rollover and dived for the deck, flew along the Esk River, up over a bridge, down the other side, standing the Moth on each of its wing tips while taking the bends of the river. He then flew up about 500 feet and dropped straight down into the ’drome for landing, which was at that time a 500-acre ordinary sheep paddock without any runways.

“This sort of initiation was frowned upon because it either killed off the pupil’s enthusiasm for flying or at least made them air sick … but not this wannabe pilot. This instructor showed me that he had good control of this aircraft and that the Tiger Moth was an excellent training plane. He also taught me not to fear fear itself. He was a good instructor, and I’m glad I had him.

“But Flying a Tiger Moth was not exactly a picnic, especially at 5.30 am in cold Tasmania. Take-off included low flying, then swerving in and out of telegraph poles, aerobatics, spins, cross-wind landing, and landing as close as possible to the inside of the perimeter fence.”

Owen Cook during the war. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

The instructors would bet on which trainee could get closest to the fence. For Owen, it was an exciting time.

“After only four and a half hours’ instruction I was told to do a cross-wind landing, then the instructor got out of his seat and told me to go solo,” Owen said.

“The last phase included night flying, then a cross-country navigation solo flying exercise; a total flying time of 16 hours. Then one day when I was coming into land, I found myself face-to-face with a twin-engine DC3 Melbourne-to-Hobart plane. When the wind speed was eight miles an hour or less, the DC3 mail planes were allowed to land in any direction. I just went full throttle to 100 mph and climbed over the top [of the DC3].”

Owen was selected for secondary training with the No. 6 Empire Flying Training School in Canada. He sailed from Brisbane on board the American troopship President Monroe, and remembers passing the hospital ship Centaur “which was lit up like Luna Park”. It was travelling in the opposite direction at the time and was sunk by a Japanese submarine shortly afterwards.

In Canada, Owen learnt to fly Harvard aircraft and had to master the Link-trainer or flight simulator.

“Instrument flying in cloud or at night was a number one priority,” he said. “On the runway, instructors would place a hood over the trainee’s head, so that they couldn’t see outside the plane, only his panel of instruments. Then he would have to take off down the runway and fly a circuit around the aerodrome then land again … Who said flying was easy?”

In late 1943, after enjoying a week’s leave in New York, he boarded the troopship Mauritania in Canada and sailed for England.

“We spent seven days in thick fog and rough seas,” he said. “The fog probably helped protect us from enemy planes, but it wasn’t a pleasant trip. You couldn’t see the sea from the upper deck.”

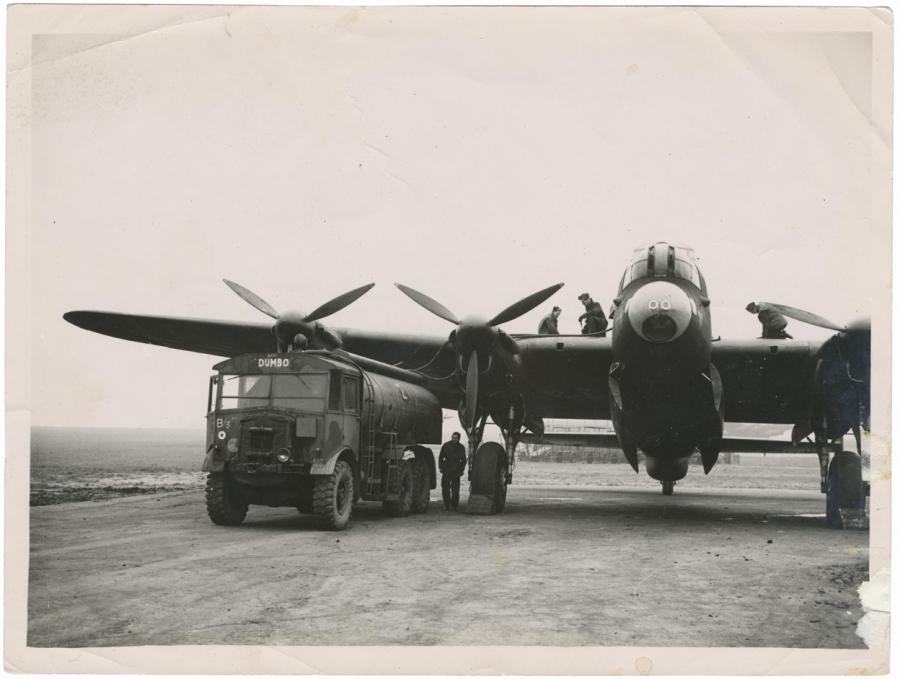

A Lancaster bomber. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

When they arrived in Liverpool, they caught a train to London and then on to Brighton in Sussex.

“Arriving in England was a real culture shock,” he said. “There were air-raid sirens going off at any time during the day and night. There were boarded-up shop fronts, and the beaches were mined and barb-wired. The whole of the UK was an arsenal of troops and war machinery, with British fighters outbound during the day and heavy bombers outbound at night.

“Aeroplane take-offs and landings were 24/7. There were blackouts every night, and there were food shortages – no fruit, but plenty of beer or spirits. The roofs of all the big hotels had anti-aircraft guns on top, and they were manned day and night.”

He learnt to fly twin-engine Oxfords at Bath – “There was no runway, just a big paddock” – and was recommended for heavy bombers. He was sent for training at Wing aerodrome in Buckinghamshire, where he had to select a crew of five other men – a navigator, a bomb-aimer, a radio operator and two gunners.

Owen Cook's crew, taken in Nottingham, November 1944. Back row, left to right: Kenneth Saunders, mid upper gunner; Owen Cook, pilot; John 'Jock' Gray navigator. Front row, left to right: Peter 'Butch' Fletcher, rear gunner; R. 'Fishpond' Fisher, air bomber; and Jack 'Mitch' Mitcherson, wireless operator. Flight engineer Duncan Walker is not present in photograph. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

“All the air crew members assembled in this particular room and you chose each other,” he said. “You didn’t know them, but you had to crew with someone. I went over to a navigator, a Scotsman called John ‘Jock’ Gray, who was sitting next to a bomb-aimer, who came from West Yorkshire, Fisher was his name. I came across an Australian radio operator, John ‘Mitch’ Mitcherson, and then we all went off and chose two English gunners. The two gunners were both just 19 years old, and I was the oldest at 22.

“We had seven days to learn the twin-engine bomber, the Wellington. It was a good aircraft but had been well used on operations over enemy territory.

“The first day I flew it with my new crew and an instructor, the brake pressure dropped to zero, which meant that I gave the crew an order to take up crash position before I attempted a landing.

“Fortunately we were using the longest runway for landing a heavy aircraft for the first time, so it became an incident rather than an accident.”

After two months of day and night flying, including cross-country navigational exercises and gunnery exercises for the gunners out over the Irish Sea, they were posted to a Heavy Conversion Unit at Bottesford aerodrome, flying the four-engine Lancasters with Bomber Command. It was there that he picked up the final member of this crew, a Scottish engineer, Duncan Walker.

“We were now a crew of seven; two Australians, two Scots, and three English,” he said.

“We had been on an exercise of fighter affiliation at night, having a Spitfire attacking our Lancaster from different directions to give the gunners aircraft recognition. This was done at 15,000 feet on a moonless night. On coming down to land again there was no brake air pressure, and once again the longest airway was in use. I had the engineer shut down all four engines and we trundled down the runway, keeping straight with the rudder, and finally stopping in a ploughed field. There wasn’t any damage to the aircraft but I had my hands on the wheels-up lever in case the plane veered further off course.

“Another night while we were training we were sent on a dummy raid into France to draw German night-fighters away from the main British force going into Germany.

“Training on the station was fairly intensive and we were now ready for action.”

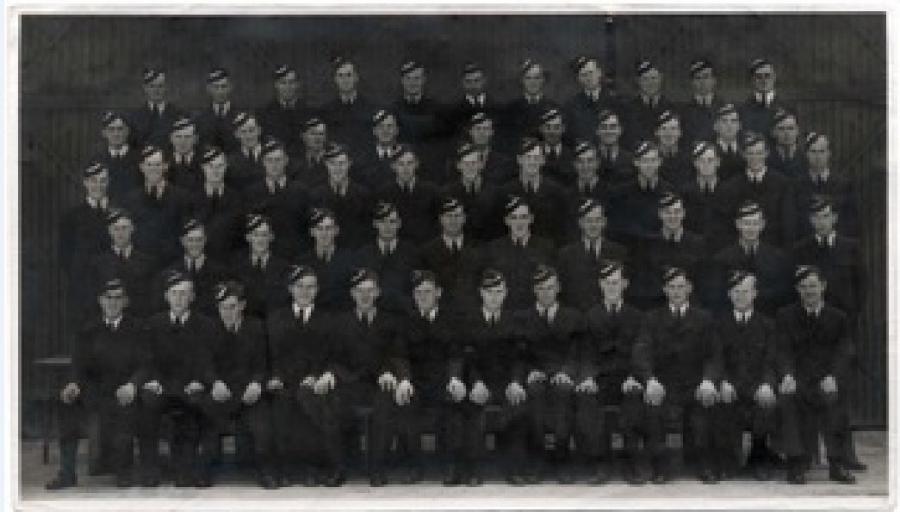

Group B 75th NZ Bomber Squadron 1945. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

He was posted to No. 75 (NZ) Squadron, based at RAF Mepal, in Cambridgeshire, about 10 kilometres west of Ely.

“For my first war operation, I went as a second pilot with an experienced crew in a ten-hour night raid to Dessau in far east Germany,” he said. “The Russians were being harassed by a large German garrison and they requested our help.

“We were one of 800 planes, which were all in formation of three abreast at 20,000 feet. We had 10/10 cloud cover, which meant full cover … and the bombers flattened the joint.

“There was plenty of flak over the target but there wasn’t any damage to our plane or injuries to our crew.

“This was an important operation for a new pilot on the squadron. If he didn’t return, his crew was classed as a headless crew and they had to return to a training unit to pick up another pilot. There was also a saying amongst the air crew that if the pilot doesn’t come back ghostly white, and his voice hasn’t gone up three octaves, he didn’t get to the target.”

He did five operations straight with his new crew before getting a week’s leave.

“A pilot taking off in a loaded Lancaster for the first time also had a culture shock,” he said. “Even at the end of a runway one-and-a-half miles long, the aircraft labours into the air. It seems unreal, but in all this time in training on various aircraft, none of us had flown a fully-laden aircraft. Who said flying was fun!

“On my first operation with my crew I was a given a parachute with the number 13 so the WAAF took it back and gave me another number. It would not have fazed me. The service manual I had in Canada was number 13 and I had also arrived in Brisbane on the 13th. It didn’t affect me.”

His last operation was a daylight raid on Helgoland, a small island in the North Sea, just north-west of Kiel, Germany.

“It was a German well-fortified submarine base,” he said. “It was a perfect spring day, no clouds and no enemy aircraft.

“There were a thousand bombers and there could have been another thousand fighters, including Spitfires, Hurricanes, Tempest fighters and Mustangs.

“The fighters beat up the German E-boats [gunboats] heading for Germany and the bombers blasted the U-boat pens, plus everything else surrounding them.

“It was a sight never to be forgotten.”

A trolley load of food about to be loaded aboard a Lancaster bomber as part of Operation Manna.

A Lancaster aircraft engaged in the repatriation of prisoners of war from Europe as part of Operation Exodus.

In April 1945, Owen took part in Operation Manna, dropping sugar bags of food over Delft and The Hague in the Netherlands. “Thanks, boys” was written on the roof of one of the houses.

“I saw the Germans with their arms crossed as we came over the coastal defences and the Dutch people waving and smiling as we flew low and slow over to do our drops,” he said.

“The war [in Europe] officially finished on 8 May 1945. It felt like no big deal. We went to a nearby country tavern, and had a few drinks. Everyone just felt numb because the end was so sudden. After six years people couldn’t believe the war was over.”

In the weeks after the war in Europe, Owen took part in Operation Exodus, flying prisoners-of-war back from Juvincourt in France to England.

“We loaded soldiers into the Lancaster and their belonging into the bomb bay,” he said. “Most of the POWs had acquired sporting rifles, cameras, binoculas, champagne and much more. I didn’t ask to see their receipts.

“The Australian POWs were placed in the gunner’s compartments so that they could take photographs of the white cliffs of Dover or other parts of the south coast of England if they wanted to.

“All their ill-gotten trophies were stored in the Lancaster bomb bays, so opening these was a delicate operation.

“They were very happy men, except one who was being brought back to England as a collaborator. I've wondered what became of him.”

Returning home: On board Andes in the Suez Canal in 1945. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

Owen returned to Australia in October 1945 on board the passenger liner Andes.

“We came home through the Suez Canal and it took 23 days and a few hours,” he said. “Apparently it is still a record run between England and Australia.

“We arrived at Station Pier in Melbourne about a week before Caulfield Cup Day. I knew my family would be there, as it was in the daily papers. But amongst the large crowd I couldn’t find them, so I climbed up on something high and then I noticed them.

“That night my father asked me if I had seen any action. My mother told him not to bother me. I hadn’t told them I was in for action till then.

“That night when I went to bed I wept for the first time since I’d left Australia.”

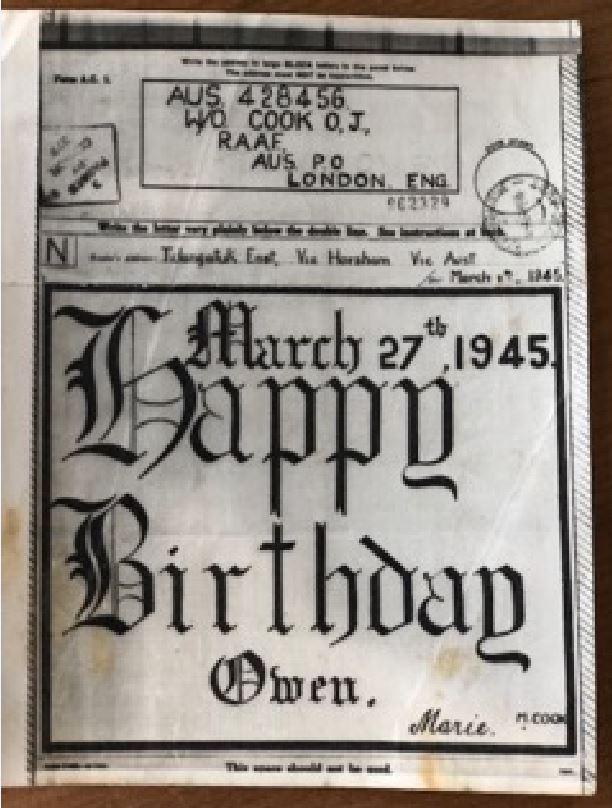

Owen's sister, Marie Cook, sent this birthday message to mark his 24th birthday in 1945. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

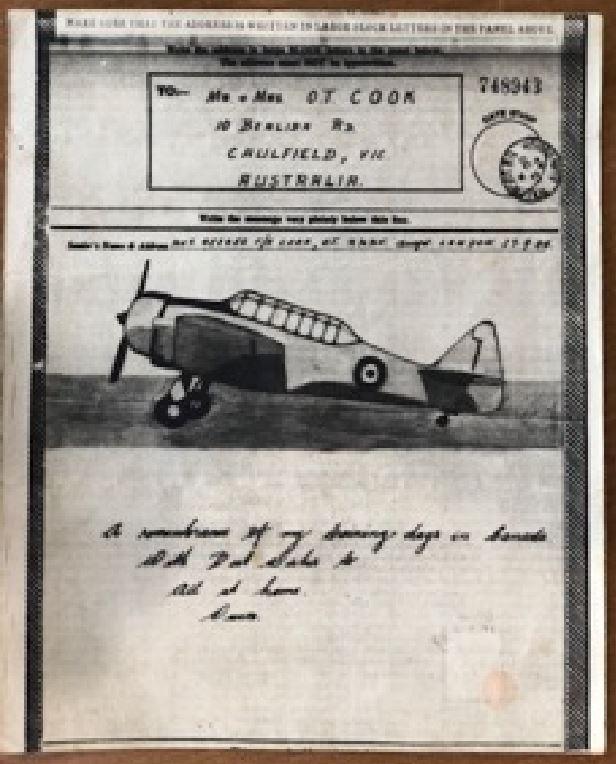

A note Owen sent to his parents from London in September 1944. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

More than 55,000 members of Bomber Command had been killed during the war, in raids over enemy-controlled Europe, training exercises and accidents on the ground. Of the 10,000 Australians who served with Bomber Command, more than 4,100 never returned. Owen was one of the lucky ones. He returned to Melbourne and met his future wife, Faye, in Swan Hill; later they started a family in Geelong. They have eight children, 14 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

“The air force treated me quite well, and I liked every bit of it,” he said.

“During the war, my crew and I all decided and agreed, that if we were going to make it through alive, there would be no carousing and we would focus totally on our job. We all kept to that promise.”

He and his wireless operator, Jack Mitcherson, remained close friends after the war, but lost contact with each other in the 1980s.

75 (NZ) Squadron RAF Crest: the crest was painted by a man named Greenham, a commercial artist who was from Caulfield in Melbourne Victoria where Owen lived at the time. They were both waiting for the troopship to bring them home after the war. Someone had drawn a little black-and-white sketch of the mascot and Owen paid 10 shillings for the man to paint it for him. Photo: Courtesy Owen Cook

In 2012, Owen travelled to England for the unveiling of the Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park, London. He also returned to Mepal airfield, where he met a young man whose father had also flown with the 75th New Zealand Squadron during the war.

“On a website dedicated to his father and the 75th NZ Squadron, the young man wrote that he had realised after our meeting that I had flown one operation with his father as second pilot,” Owen said. “He was the bomb-aimer of the crew I flew with on that first flight over Dessau. My old mate Jack Mitcherson's daughter happened to see the web post, recognised my name and contacted me. Jack and I were reunited after 30 years.”

His advice to young servicemen and servicewomen today: “Be in everything and volunteer for everything you can. Your flying days will be over much faster than you can imagine.

“Although we didn't all keep in contact for many years after the war, I will always remember my crew. We went through a lot together.

“I’m now perched on the top twig of the tree awaiting my next posting …

“I never ever thought I was going to live to this age, because I’ve been through a war, but I was never a drinker, I was never a smoker, so here I am.”