'It's about respect, and recognising people for who they are'

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons. It also contains racist terms and descriptions, the use of which reflects language and attitudes of the time.

We have chosen not to identify the servicemen and families referred to in this article to respect the wishes of the families and descendants involved.

Imagine having to lie about who you are to serve your country. That’s exactly what one soldier had to do to enlist during the Second World War.

One of thousands of Indigenous Australians who served during the war, his name is now recorded on the Australian War Memorial’s new Second World War Indigenous Service List.

Danusha Cubillo, a proud Larrakia woman, has been working on the list with the Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell. The soldier’s story is one of many that Danusha has uncovered during her research into Indigenous service.

“I’d come across him quite early on in my research, and something just drew me to him,” she said.

“The thing that first captured my attention was that he had lied all over his Attestation Papers when he enlisted.

“He lied about his birthdate. He lied about where he was born. And he lied about his mother. Everything on there was just a fabrication, and when I went researching I found it wasn’t true; he’d even lied about his name.

“I thought there’s got to be a story behind him, and as I delved further into it, I found out there was. He had signed up a couple of times, and had been kicked out the first time because he was Aboriginal, so he concocted this whole new identity and signed up again.

“He ran into a bit of trouble while he was in, and faced a few court martials, but in one of the court martials he says he’s had difficulties in some of the units because of the colour of his skin and because he is what he calls – and these are his words – a ‘half-caste Aboriginal’.

“He goes on to say that when he went to go into a pub, they wouldn’t serve him because he was Aboriginal, yet it was okay that he was in uniform and fighting for his country.

“He says that he didn’t abscond and that he didn’t run away, he just couldn’t stand it anymore that he was being treated differently because of the colour of his skin … and that makes you quite sad.

“He was charged and found guilty, not guilty of desertion, but guilty of being absent without leave, and there are quite a few records that are very similar to his.

“This is a guy who lied all over his paperwork to enlist, and when you start investigating, you find out there’s a whole other story that unfolds.”

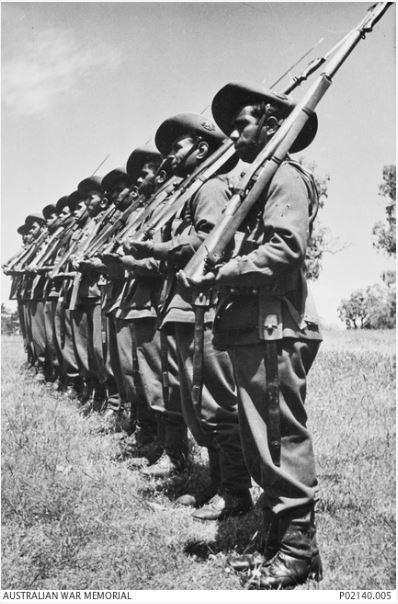

Aboriginal servicemen standing to attention, at No.9 Camp at the Wangaratta showgrounds in Victoria. These men were mainly volunteers from the Lake Tyers mission, known as Bung Yarnda, by the local Gunai/ Kurnai community, in Eastern Victoria. The men volunteered together, either in the first intake, on 15 June 1940 or the 14 and 25 July 1940. In 1940, the Defence Committee stated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples enlistment in either the Army or the Navy was “neither necessary nor desirable.” As a result, all of these men were discharged on 22 March 1941, their records stating “Services no longer required: not due to misconduct or discreditable service”.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a long tradition of fighting for Country and have served in every conflict and commitment involving Australian defence contingents since before Federation.

When the Second World War broke out, Indigenous Australians were still not legally allowed to enlist, but many did so, and in 1940 the Defence Committee decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was “neither necessary not desirable”, partly because they believed white Australians would object to serving with them. When Japan entered the war, however, the increased need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions, and thousands of Indigenous Australians enlisted and served – including Danusha’s grandfather, Delfin Antonio Cubillo.

“I’ve always had an interest in the Second World War due to stories my grandfather told me,” she said. “I grew up in Darwin, and they still have preserved sites that resulted from the bombing of Darwin. Growing up, and seeing it there every day, you want to know more, so I became interested to really discover what it was like for people at that time.

“For me, it’s been like a trip down memory lane through the eyes of other people, to be able to see how different people lived in different parts of Australia, and how we are all different, and from all different mobs, but we all banded together and fought for Australia.”

The idea for the Indigenous Service list first began when the MP Don Cameron put an ad in national newspapers around the country asking people to write to him with the names of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people who had served.

Memorial volunteer Margaret Beadman also spent years working to identify Indigenous Australians who had served, compiling reams of information which was digitised with the help of Squadron Leader Gary Oakley, a proud Gundungurra man and former Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial.

Earlier this year, Danusha was seconded to the Memorial from the Department of Defence through Defence Indigenous Affairs. She has added hundreds of names to the list and confirmed others with the help of Dubbo historian Sandra Smith.

For the purposes of the list, the term Indigenous is understood as referring to the Indigenous peoples of territories administered and/or occupied by Australian forces: Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islanders, South Sea Islanders and Papuans. Details have been taken from publically available records, including state and national archives, newspaper articles, genealogical material, family memorabilia, and oral histories.

Informal portrait of two Indigenous servicemen, NX31736 Private Frederick Beale (left) and his brother NX31660 Pte George Henry Beale (right), with NX31623 Pte Michael Joseph (Joe) Lynch (centre), all of the 2/20th Battalion. All three were captured, and became prisoners of war in Singapore after its fall on 15 February 1942.

“My work here is discovering or finding hidden names that we didn’t know before,” Danusha said.

“You can just look at one bit of paper, and sort of get a feeling for the passion they had and why they wanted to join.

“It’s been a team effort, and we have around 2,000 names now, but it’s a living document, and the research is ongoing, so if you have a name of someone who has served we’d love to hear from you.

“With a little bit of information you are able to start digging and find out more.”

New names are constantly emerging, while some have been removed after research identified them as non-Indigenous.

Only rarely was it noted on a soldier’s attestation papers whether they were Aboriginal; often there was just a description, specifying dark complexion, dark hair, or brown eyes, that was entered. However, note was made of a soldier’s Aboriginality, in the event of his being discharged as unfit for service because of it.

Danusha tells the story of a 48-year-old man who enlisted during the Second World War and was discharged two years later because he was Indigenous.

“He’s 50 years old by now, and he’s blind in the left eye, and he is being discharged because his services are no longer needed,” she said. “It makes me ask, why? And then you see it’s because he was Aboriginal. He’d been serving for the last two years – he’s blind in the left eye, and he was 48 when he enlisted, so he wasn’t a young man, but he still signed up, and that shows the passion some of these people had; they really wanted to do something for their country.”

She also uncovered the story of a 22-year-old Indigenous man who was reported missing, believed killed in action, during operations off Greece.

“That’s it; that’s all that’s written, and to me looking at it now on paper, that’s that person’s life over,” she said. “The file ends, and you find no more, but what does that mean for the people back at home who are now without their son, their husband, their father? How do they then deal with everything and get on with life?”

She was also moved to discover the story of an Indigenous soldier who lost his arm during the war.

“He’s served in Greece and the Middle East, and he’s had his left arm amputated after being wounded,” she said. “He was 21, and he’s had a gunshot wound to his right hand as well. His whole life changed, but how did that moment in time then change the rest of his life?”

Danusha Cubillo at the Memorial with Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell.

Indigenous Australians who had fought for their country returned to much the same discrimination as before when the war ended, and many were barred from Returned and Services League clubs, except on Anzac Day.

“People are still under the Aborigines Protection Act so it’s not like you have the general freedoms that are afforded to everyday Australians,” Danusha said.

“It did change people’s perceptions and it did make people think differently about working alongside an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, but then when they got home they were still subject to that act and everything else that went along with it, which means any money that you would have got or any land or anything else would go straight to the Protector of Aborigines and he would decide if you deserved it or not, so it was a bit of a slap in the face.

“We’ve uncovered people who were Aboriginal, but they didn’t say so at the time, or openly acknowledge that they were. They had been told by their mother to never tell anyone that they were Aboriginal and it became a lifelong family secret so that they could get ahead in life and not come across the persecution of the Protection Act.”

She is encouraging anyone with information about Indigenous servicemen and servicewomen to contact the Memorial.

“The work that we do is actually a step toward reconciliation, and what we are doing is putting an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander face on the Anzac legend,” she said.

“People can be angry at the past, and people can be angry at the things that people did in those periods of time, but what we have to focus on is making sure that we don’t make those same mistakes in the future.

“It’s about respect and giving that person their due. They fought for this country, and we want to acknowledge them for who they are, and be able to tell people proudly who this person was.”

The Indigenous Service list is now available online.

Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial, is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au