'We didn’t know what our future would be'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people.

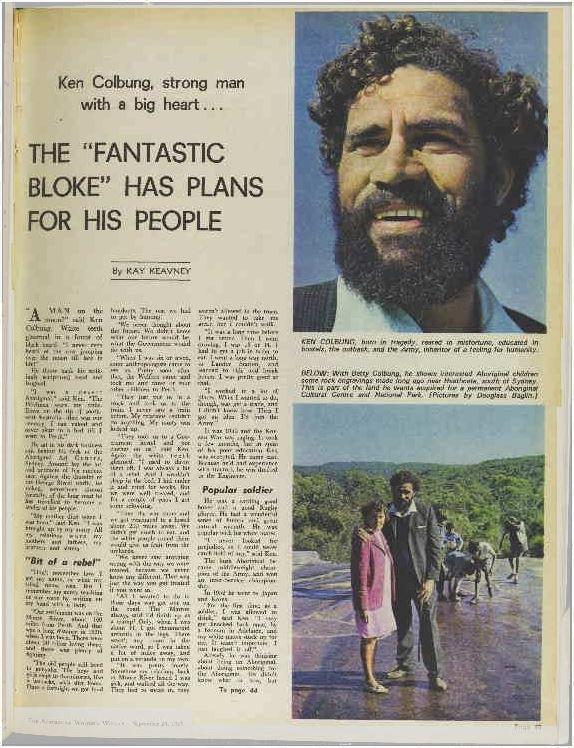

Ken Colbung was one of more than 60 Indigenous Australians who served in Korea. Photo: DVA

Ken Colbung was a “strong man with a big heart”.

A prominent Aboriginal activist and respected Noongar Elder of the Bibbulmun people, he was described as a “fantastic bloke” who had big plans for his people.

Becoming an active campaigner for the recognition of cultural and human rights for Aboriginal people, he was actively involved in the Australian Black Power Movement of the 1960s.

He never forgot his service. A veteran of the Australian Army, today he is recognised as one of more than 60 Indigenous Australians who served in Korea.

Also known by his Indigenous name – Nundjan Djiridjarkan – Kenneth Colbung was born at the notorious Moore River Native Settlement in Western Australia on 2 September 1931.

Sharing his story in the pages of the Australian Women’s Weekly in September 1969, Colbung recounted: “I was a desert Aboriginal. The Pibelmen [Bibulman] were my tribe. Down on the tip of south-west Australia – that was our country. I ran naked and never slept in a bed till I went to Perth.

“My mother died when I was born,” he told the Weekly. “I was brought up by my aunty. All my relations were my mothers and fathers, my brothers and sisters. I don’t remember how I got my name, or what my tribal name was. But I remember my aunty teaching us our ways by writing on my hand with a twig.

“Our settlement was on the Moore River, about 160 miles from Perth. And that was a long distance in [the] 1930[s], when I was born. There were about 50 tribes living there, and there was plenty of fighting. The old people still lived in gunyahs. The boys and girls slept in dormitories, like a barracks, with dirt floors. Once a fortnight we got food handouts. The rest we had to get hunting. We never thought about the future. We didn’t know what our future would be, what the Government would do with us.”

Ken Colbung shared his story in an article in The Australian Women's Weekly in September 1969.

At that time, the Chief Protector of Aborigines controlled every aspect of First Nations people’s lives, and was the legal guardian of every Aboriginal child.

Colbung was removed from his family at Moore River when he was six. Sent to live at Sister Kate's Children's Cottage Home in Perth, the boys were trained for manual labour, while the girls were trained as domestic servants.

“When I was six or seven, some anthropologist came to see us,” Colbung told the Weekly. “Pretty soon after that, the Welfare came and took me and three or four other children to Perth.

“They just put us in a truck and took us to the train. I never saw a train before. My relations couldn’t do anything. My aunty was locked up. They took us to a Government hostel, and put clothes on us. I used to throw them off. I was always a bit of a rebel. And I wouldn’t sleep in the bed. I hid under it and cried for weeks. But we were well treated, and for a couple of years I got some schooling …

“Then I went droving. I was 13 or 14. I had to get a job in order to eat. I went a long way north, to Landor Station and learned to ride and break horses. I was pretty good at that. I worked in a lot of places. What I wanted to do, though, was get a trade, and I didn’t know how. Then I got an idea. I’d join the army.”

Colbung enlisted in 1950 at the age of 19. As an Aboriginal man in the 1950s, he could not travel interstate or vote, but as a soldier in the Australian Army he could be sent overseas to serve in Japan and Korea.

“For the first time, as a soldier, I was allowed to drink. I only got knocked back once, by a barman in Adelaide, and my white mates stuck up for me. It wasn’t important. I just laughed it off.”

Colbung completed his training with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, at Puckapunyal, Victoria, and served with the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force.

He deployed to Korea with 3RAR in January 1954, during the Armistice enforcement period, and was involved in training and border patrols before the battalion returned to Australia in November 1954.

Korea, April 1951: Korean refugee women and children with their personal belongings arrive at Suwon in a cart being pulled by a bullock.

Colbung spoke about his experiences in a radio interview with the ABC in 1998. Having travelled from Japan to Korea, Colbung took a train to Ŭijŏngbu, “where I had my first shock reaction”. The sight of thousands of displaced women and children would stay with him forever.

“I mean, the sound of war, is nothing. It's the sound of humanity that's involved in war that's probably more deadly than any bullet ... It’s more discerning than any shell blast that you could ever recollect.”

Compared to the experience of probing an anti-personnel mine that exploded, “that was nothing to what I’d leave with, the cries of women and children,” he said.

“These children were probably no older than the children we have here at our primary school ... The Salvation Army was ... looking after them. But 5,000 children, you have to see it, to believe it.

“[We] handed out all that we could. We gave everything that we had ... We were told not to, but we went against that because we were young and we had feelings, but we wish we’d listened.”

He spoke of his horror at seeing young children committing atrocities on one another while competing for food, soap and cigarettes.

“That was my first contact with war,” he said. “I was completely shocked by it all ... even today I can ... [hear] the screams of these young children. I was looking at a scene ... I never ever want to see in my life again ... where children were fighting for their lives.”

Korea, c. 1951: A stream of North Korean refugees consisting of men, women and children trudges along a track in a snow-covered landscape.

Korea, c. 1950: A stream of Korean refugees trudges along a dusty road away from the war. The refugees, mainly women and children, are carrying their possessions on their backs or in bundles on their heads.

The impact of three years of war on the landscape also shocked him.

“To look at what war and the carnage that war had done there... my heart... was ... torn at the damage done to the land.”

Colbung found returning to civilian life difficult. More than 50 years later, he recalled the challenges in his interview with the ABC.

“The smell of humanity was very strong,” he said. “These are things that stick out in my mind in Korea ... not a part of any terrible war, or a scourge that was coming down, but human versus human … I thought it would have gone away, but it hasn’t. It’s influenced me a lot to respect our own vegetation and our own environment, but more so to respect humanity ... and to understand and respect another man’s religion and another man’s belief ...

“In Korea, I saw that poverty. That poverty was with those 5,000 children. That’s something [I] never want to see...

“They’re the things that come with war. Wars should never be ... We should look more for peace. We should aim for it. We should strive our utmost to have a peaceful outlook on life and we should educate our children to respect ... not only us, but people right around the world.”

He credited his family for helping him through his darkest times. Not long after leaving the army, Colbung met Betty May Beale, who was raising five young children from a previous marriage.

Colbung loved the children as his own, and he and Betty had a daughter.

“I kept thinking about those children,” Colbung told the Weekly. “They reminded me of being a kid myself, and having nothing and no one. Give the money to them, not the grog, was what I thought.”

Pusan, South Korea. 9 November 1954. Members of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), and the 16th Royal New Zealand Field Artillery Regiment, wave from the rail as the SS New Australia leaves the wharf at Pusan to return home.

Pusan, South Korea. November 1954. Members of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), embark in the troopship TSS New Australia at Pusan to return home.

Colbung went on to become a prominent advocate for First Nations people, and was instrumental in developing the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, which governs the protection and preservation of Indigenous heritage sites in Western Australia.

In recognition of his efforts, Colbung was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1980 and the Order of Australia Medal in 1982. Two years later, he became the first Indigenous Chairperson of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

He would spend more than 20 years of his life searching for the remains of his ancestor, the Noongar leader and resistance fighter Yagan, who was killed by white settlers in 1883. The warrior’s severed head, held at a British museum before being buried in the 1960s, was returned to Perth in 1997.

“What Yagan did in his day was to sort of bring about the fact that we’re human, all together,” he said. “I can remember as a child that they said that we weren’t humans at all.

“At six o’clock in the evening, the mothers and fathers would gather us and take us out of the town six miles away. We had to leave the town site. We had one toilet in the whole of Perth for Aboriginal people. The rest of the toilets were for white people. We could not travel in the carriages with them. We had to travel in separate native carriages and they were attached to the trains that picked up the stock, the animals and the fruit for the markets ... It’s not hundreds of years ago we’re talking about. It’s only within the past 50 years that those sorts of things were here ... so I have lived through it.”

Yagan’s remains were reburied in the Swan Valley in July 2010, about six months after Colbung’s death on 13 January 2010.

Colbung hoped for a better life for his people. “Already there are changes,” he told the Weekly in 1969. “Things will be easier for my sons than they were for me.”

Ken Colbung is one of more than 60 Indigenous Australians known to have served during the Korean War. The Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer, Michael Bell, has been working to identify and research the service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is interested in further details of the military history of all those people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au