The greyhounds of Kokoda

The 39th Battalion was seen as heroic but the 53rd Battalion was derided; the clues lay in the circumstances of their formation.

Soldiers from the 30th Brigade carrying out manoeuvres in Port Moresby, July 1942.

Toiling under the weight of their weapons and equipment, the young Militiamen slowly trekked their way across the exhausting rises and falls of the Owen Stanley Range. Torrential rain fell practically every afternoon and night, soaking the men and turning the narrow Track into a muddy morass. Signalman Harvey Blundell summed up the conditions, in one word – “terrible”. It was “up and down ’em bloody mountains” every day, remembered Private Mick Button. Soldiers did what they could to lighten their load, throwing away some of their kit and cutting their blankets in half. The cautious among them also collected extra ammunition and grenades.

As the first of these soldiers from the 53rd Battalion reached Alola in mid-August 1942, a few kilometres further north the 39th Battalion had fallen back to Isurava and dug in with their “bayonets, bully beef tins and steel helmets”. Here they received a new commanding officer, the redoubtable Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, who arrived to replace Lieutenant Colonel William Owen, mortally wounded at Kokoda. Honner thought the battalion looked to be in poor shape: worn out by the strenuous fighting and movement, weakened by lack of food, sleep and shelter, and constantly wet.

The Japanese crashed into the 39th Battalion’s forward positions at first light on 26 August. Bitter, close-quarter fighting ensued over the following days as the Japanese 1st and 3rd Battalions, 144th Infantry Regiment, repeatedly attacked Honner’s men, now reinforced by the fresh AIF troops from the 21st Brigade’s 2/14th Battalion. Honner later wrote:

The enemy came on in waves over a short stretch of open ground, regardless of casualties ... They were met with Bren-gun and Tommy- gun, with bayonet and grenade; but still they came, to close with the buffet of fist and boot and rifle-butt, the steel of crashing helmets and of straining, strangling fingers. [It was] vicious fighting, man to man, hand to hand.

The exploits and achievements of the 39th Battalion, those “ragged bloody heroes”, at Kokoda and Isurava have been quite rightly celebrated. Footage of the exhausted members of the battalion parading at Menari, in Damien Parer’s Kokoda front line (1942), has provided some of the iconic images of the campaign.

The story of the 53rd Battalion is less well known. As the fighting at Isurava was taking place, 53rd became involved in a confused action along the Alola–Missima track that ran to Kaile. After some initial patrolling, the battalion’s B and D Companies were to have attacked Abuari and reoccupied Missima on 27 August, thus preventing the Japanese from possibly outflanking the Australians at Isurava.

Moving through Missima, Japanese soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, 144th Infantry Regiment, occupied the higher ground south-east of Abuari. They easily broke the Australian attack, and the 53rd Battalion’s commanding officer was killed in an ambush. Some men tried to make their way forward through heavy jungle and rough terrain. However, it was reported that one company engaged the Japanese but then “broke and scattered”, while the other seemed to do little more than fire back at the Japanese. Seventy men were thought to have “taken to the bush”.

The battalion’s war diarist attributed its reverses to the nature of the country, the heavy Japanese machine-gun fire and the “lack of offensive spirit and general physical condition of the troops”. Two days later, on 29–30 August, the 53rd Battalion’s D Company gave a less-than-impressive performance when it attempted to outflank the Japanese position in support of the 2/16th Battalion’s attack on Abuari.

After two months on the Kokoda Trail, including the actions at Kokoda and Isurava, members of the 39th Battalion parade at Menari, 22 September 1942.

The reputations of the 39th and 53rd Battalions were sealed immediately. In the 21st Brigade’s after-action report, written in October, the men of the 39th Battalion were praised for their high morale and their “steadiness” under repeated Japanese attacks. Of the 53rd Battalion’s men, on the other hand, it was said that despite being fresh, they soon “demonstrated they lacked tng [training] and discipline”.

Major Bill Watson, who served alongside the 39th Battalion at Kokoda and Isurava, succinctly commented that it was the Militiamen’s ability “to give it and take it” that impressed those who saw it in action: “they had great guts”. In contrast, Captain “Doc” Vernon described men from the 53rd Battalion going forward near Efogi in mid-August as “the most spent and disheartening looking of our troops I have seen, yet they have to go into action shortly”.

Low morale, inexperienced leadership and poor training are the standard explanations for the 53rd Battalion’s failures. These are not unfair criticisms. Both the 39th and the 53rd Battalions, however, had received little training in infantry tactics since arriving in Port Moresby eight months earlier, and virtually none in jungle warfare. The respective strengths and weakness of the two battalions had been present since their earliest days.

The 39th Battalion was raised in October 1941 at Darley Camp, north-west of Melbourne, when the army’s headquarters decided to raise a new battalion specifically for tropical service to relieve the 49th Battalion in Moresby. The 39th Battalion was formed with officers and men drawn from different Victorian Militia units. Potential officers and senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) had to apply for positions within the battalion.

Fifty-two-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Conran was appointed to command the battalion. Conran was a strict disciplinarian and an experienced officer, serving in the infantry during the Great War and then in the Militia during the interwar period. Conran personally interviewed all officer applicants and he recognised the value of having experienced officers and men in forming his new battalion. Ten of the battalion’s original officers were also veterans and many of the others, including four lieutenants, were aged in their 40s. There was also a cadre of experienced NCOs. Eleven warrant officers and sergeants, and a private, were “returned men”; three of these men had been decorated for bravery; two had held commissions.

These old soldiers instilled in the younger men a sense of pride and esprit de corps

These old soldiers instilled in the younger men a sense of pride and esprit de corps in their new unit. Keith Lovett, who accepted a demotion from captain to lieutenant to join the battalion, considered that one of its strengths was the “training given by these older, experienced” men who “stood by us when we went into action. The young officers, like myself, learnt a lot from them.” This was a strength that the 53rd Battalion did not possess.

Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Ward’s 53rd Battalion was raised at Ingleburn camp, west of Sydney. During the late 1930s two Militia battalions were merged to become the 55th/53rd Battalion but in September 1941, plans were under way to form a new 53rd Battalion to relieve another Militia battalion in Darwin.

Too young for the first war, Ward had only limited experience commanding Militia infantry battalions, but his professional qualifications were considered to be high. He was practical, with sound judgement and a very strong character. At 38 years of age, Ward was the “old man” of the battalion, both literally and figuratively. His officers were all younger and none had seen active service. Bill Elliott, one of the battalion’s original sergeants, had the impression that the officers had little experience in the art of being an officer and were in the same situation as the men: “they were all just thrown in a heap and they were trying to sort themselves out”.

As with the 39th, the 53rd Battalion was raised in November 1941 on a quota system with men supplied from different Militia units across New South Wales. Most men had at least three months’ training, but there were about 200 men who had been called up only at the start of October.

Lieutenant Hugh Conran, 23rd Battalion, May 1915. After serving on Gallipoli, he was later wounded at Pozières the day after his brother, Lance Corporal Noel Conran, serving in the same battalion, was killed. Having raised the battalion, Conran deserves much of the credit for the 39th’s success.

After six weeks of full-time training, the battalion began to receive leave as Christmas approached. On Sunday, 14 December, the men’s family and friends were able to visit and leave was similarly granted for the following weekend afternoon. On Christmas Day leave was granted after lunch until 10 pm. Not surprisingly, when the battalion’s roll was called that night, 275 men were still absent. Two days later the battalions came together when the 39th Battalion, who had travelled to Sydney by train on Boxing Day, met the 53rd aboard the transport Aquitania at Woolloomooloo wharf. The move surprised most of the 53rd who, apart from a few hours over Christmas, had not received any pre-embarkation leave. Few knew exactly where they were destined. To make up for those still absent, the 53rd received a draft of just over 100 soldiers only hours before Aquitania sailed. These men, probably aged in their late teens or early 20s, were drafted that day from various units around Sydney and moved directly to the ship after a medical examination. They had little opportunity to say farewell to their loved ones. These “shanghaied” men are said to have held a deep grudge and resentment against the battalion and the army. Four months later Ward informed his brigade commander that there was an element in his battalion who still doggedly refused to accept the role of a soldier. Another officer commented that the battalion was “filled with odds and ends” with very little training. This did not improve after Aquitania reached Port Moresby in January 1942.

The Militiamen were sent to Papua to reinforce the 49th Battalion as the 30th Brigade. Moresby was a military backwater during 1941 and the first few months of 1942. There were no amenities or facilities for the troops. Japanese air raids were regular occurrences yet the brigade did little training. Instead they were used as labour for working parties and unloading ships. The taxing tropical climate and illness, the lack of vehicles and the dearth of amenities eroded the men’s morale.

Brigadier SelwSyn Porter arrived in Moresby in April to take over command of the 30th Brigade and found it in “a sorry state”. Porter had served in the Middle East and had a reputation as a driving force. He did what he could to improve the training syllabus and lift the brigade’s morale. He was also able to distribute a handful of junior AIF officers, with recent operational experience, among his battalions. Older men and ineffective officers were either transferred or returned home.

The 39th’s Conran was among the first to go, having succumbed to the rigours of tropical service. When Porter first met Conran, the battalion commander was bed-ridden and “almost transparently thin” with dysentery. He was replaced by Colonel Owen, who had served at Rabaul, New Britain, but had escaped after the Japanese invaded the island.

Porter was impressed with Colonel Ward, whom he thought was as good as any battalion commander in the AIF; and his officers, who were young and better presented than those from the other battalions, were “more informed and generally more alert”. Consequently the 53rd Battalion received the lowest allocation of AIF officers, most of whom went to the 49th and the 39th Battalions. Porter thought Ward’s men were shaping up more efficiently than the other two battalions.

Ward was keen to get into action, and frustrated at having to “sit” in Moresby and the constant drain on the battalion to provide labour. Even at the end of July, as B and C Companies were preparing to act as a reserve for the 39th Battalion already in action at Kokoda, the 53rd Battalion still had to provide nearly 200 men for labour. A fortnight later Ward’s battalion was making its way across the Kokoda Trail, concentrating around Alola on 20 August.

Ward sent out patrols, through the 39th Battalion at Isurava, towards Deniki and across Eora Creek to Missima and Kaile. The first contact with the Japanese came on the afternoon of 21 August, when a patrol to Missima exchanged shots with a small group of Japanese soldiers.

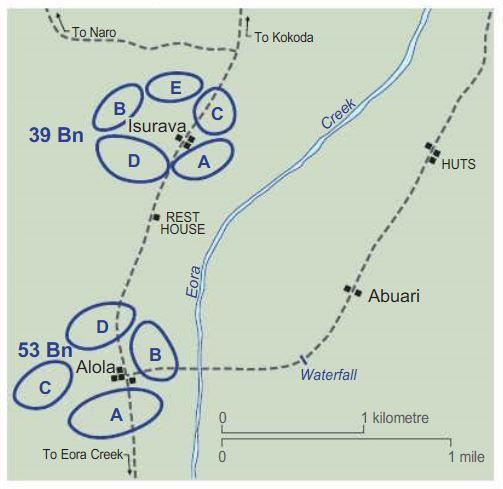

The 39th and 53rd Battalions’ respective company dispositions at Isurava and Alola on 26 August 1942.

Patrolling continued over the next few days. There were some successes, with Lieutenant William MacDonald and Captain Frederick Ahern in particular proving to be cool and skilled leaders. But when it came to a more complicated attack against an experienced enemy, the 53rd Battalion was found lacking. The failed attacks at Abuari highlighted the unit’s limited training and the inexperience of its officers and NCOs either to control their men or to encourage them forward. The battalion had been committed to action well before it was ready.

It is important to realise though that this was the 53rd Battalion’s first experience of combat. It was usual for soldiers to make mistakes during their first action, and it was not uncommon for men fighting in the jungle for the first time to become confused and disoriented. The battalion, however, was a victim of circumstance and never had a chance to redeem itself: it was only in action for just over a week. Brigadier Arnold Potts, the 21st Brigade’s aggressive commander, quickly ran out of patience with the 53rd Battalion. Arriving at Alola on 22 August, Potts soon dismissed it as a fighting force. In his opinion, its training and discipline were below standard and only suitable for guard duties; worse, the battalion lacked an offensive spirit. Potts was given approval to pull the 53rd out and replace it with the 2/27th Battalion, then being held in reserve, something the brigadier had wanted to do for days. The 53rd Battalion’s war diary for 2 September recorded that “all automatic weapons, rifles and equipment” were to be left at Myola, as the battalion was to return to Moresby. Although some men stayed behind to carry out the familiar tasks of guard duties and gathering supplies dropped by aircraft, the battalion’s active role in the Kokoda campaign was over. The news that they were being unceremoniously pulled out of the fighting came as a blow to the men, still shocked by Ward’s death and humiliated at having to leave their weapons behind. Sergeant Elliot recalled that the orders to stack their rifles, leaving them for the 2/27th Battalion, and then the march back to Moresby, “hurt the boys”. They “felt like a mob of dingoes”. They were “very depressed soldiers”, thought Signalman Blundell.

Stories and rumours of the 53rd Battalion’s conduct quickly began circulating among those serving in Papua. In one anecdote the battalion’s officers were supposed to have beaten their men in the race back to Moresby. More than 40 years later Private Button could still recall his battalion ridiculed as the “greyhounds of the Owen Stanleys”. Lieutenant Frank Budden, the battalion’s historian, wrote that many a fight resulted when the unit’s colour patch was recognised or when a man was asked, “What unit, digger?” The reply sometimes brought the remark, “That mob, they let the AIF down.”

Its confidence shaken and morale low, the battalion’s ranks thinned during September as officers and men were transferred or seconded to other units. In late October those who were left with the 53rd were merged with the 55th Battalion, which had earlier arrived in Moresby with another Militia brigade, to form the 55th/53rd Battalion. Ironically, given its earlier performance, Colonel Honner’s 39th Battalion was disbanded in mid-1943 and its personnel were transferred to other units.

Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Ward (left) and Lieutenant Rowland Logan at Port Moresby in early 1942. Ward and Logan were killed in an ambush on 27 August 1942 as the 53rd Battalion’s attack towards Missima broke down.

Once given proper training, capable leadership and experience, the 55th/53rd Battalion went on to win battle honours for itself, fighting bravely in the bloody Papuan beachhead battles in December 1942 and January 1943, and with great skill during the Bougainville campaign in 1945. Aware of its chequered history, towards the end of the war Lieutenant General Stanley Savige, the Australian commander on Bougainville, made a special point of singling out the battalion for its fine work, commenting, “The 55th/53rd Battalion will do me.”

This article was originally published in Issue 48 of Wartime magazine 'Kokoda: Then and Now'. You can purchase a copy here.