'He's that quintessential Anzac'

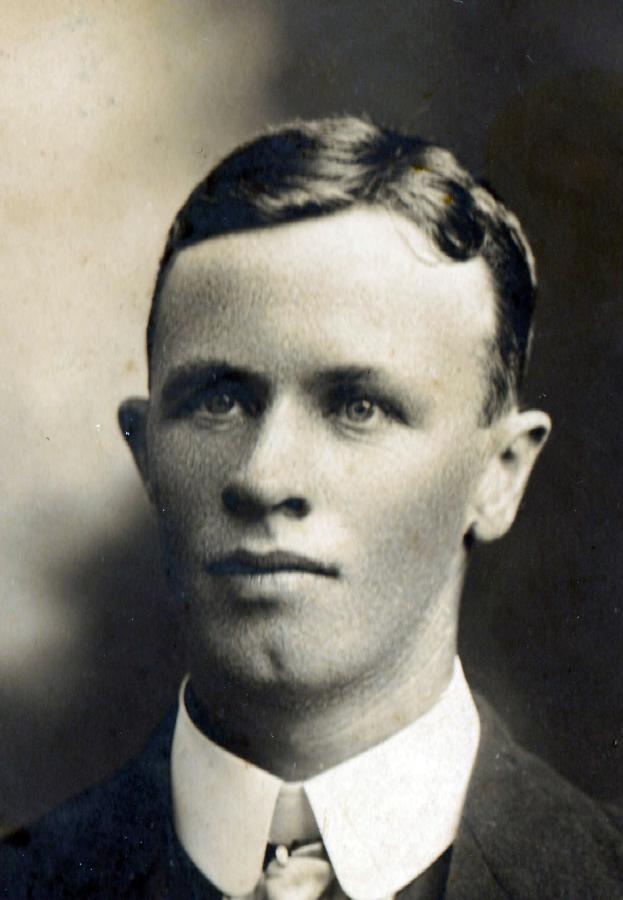

Gilbert Toplis sat for this portrait in England in October 1915. Photo: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Gilbert Toplis had seen his fair share of war.

One of the first Australians to enlist during the First World War, he landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 and was wounded at Lone Pine before serving on the Western Front in France and Belgium.

He would survive the fighting at Mouquet Farm, near Pozières, as well as the battles of Messines, Polygon Wood and Dernancourt, only to be killed by a sniper during the second battle of Villers-Bretonneaux on 24 April 1918, in the final year of the war.

More than 100 years later, his great-nephew Dr Stuart Toplis laid a wreath in his honour at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating his life at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra on the anniversary of his death.

“He's that quintessential Anzac,” Stuart said. “He’s wounded on Gallipoli, and he almost made it right through the war – he just didn't make it home.”

Gilbert as a child in Tasmania. Photo: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Known to his family and friends as Bert, Gilbert was born Gilbert Charles Bryant on 1 November 1889, at the Cascades Female Factory, a former convict facility for women near Hobart.

Shortly after his birth, Gilbert and his mother Elizabeth moved to Richmond, Tasmania, where she worked as a housekeeper for Thomas Toplis, a former convict, and the sexton at the historic St Luke’s Church. It was there that Thomas and Elizabeth were married in 1891, both mother and child adopting the surname of Toplis.

When Thomas died in 1907, Gilbert, then aged 18, became the sole support for his widowed mother and his two younger siblings: 11-year-old Minnie, who suffered from the genetic condition achondroplasia, and five-year-old Roland.

Gilbert had been working as a farm hand and ironworker in the remote Tasmanian settlement of Laprena to help make ends meet, and was helping his mother manage the Richmond pound when the war broke out in Europe.

He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force at Pontville on 27 August 1914 and was allocated the service number 139.

“He’s one of the very first Tasmanians to enlist,” Stuart said. “But his eagerness to fight might not have been for the great adventure, but rather that it offered an attractive wage – given that he was the sole provider for his widowed mother, his younger brother and his severely disabled sister.”

Group photograph of officers and men of A Company, 12th Battalion, AIF, Brighton, Tasmania, on 13 September 1914. Gilbert is pictured on the right-hand side of the photograph, circled in red.

Gilbert joined the 12th Battalion, one of the first infantry units raised for the AIF, and embarked for overseas service on board the troopship HMAT Geelong just two months later.

He landed on Gallipoli at dawn and was wounded in the head by an enemy grenade during the battle of Lone Pine on 9 August 1915. He was evacuated the following day and spent the next five months recovering in England.

He wrote to his mother from Bournemouth in October 1915 to assure her he was well.

“Dear Mother,” he wrote. “Just a line. I am having a lovely time here. In fact, the best I have had on the trip. I am enjoying myself to the utmost... (Time is short) Bert.”

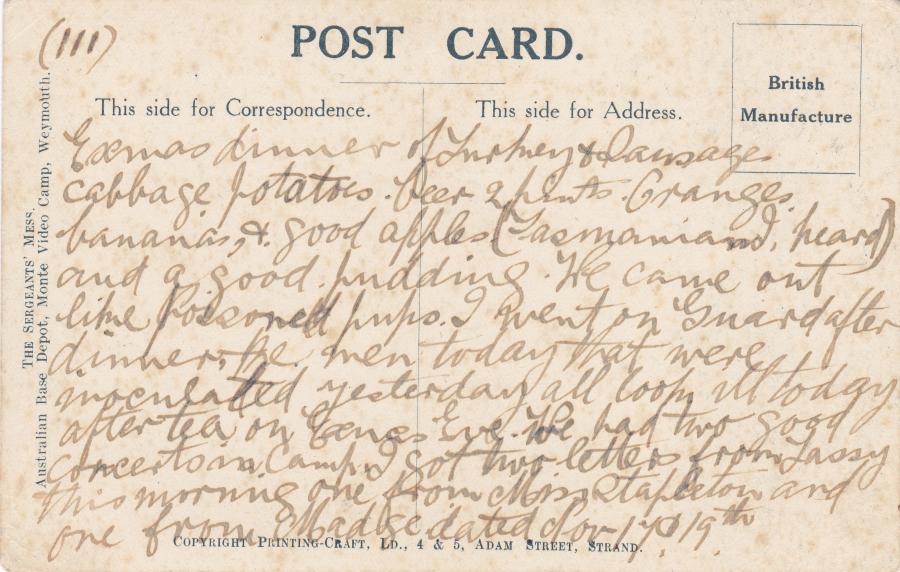

He wrote again from Weymouth, telling her he had enjoyed a Christmas dinner of turkey and sausage with cabbage, potatoes, and beer, as well as oranges, bananas and apples – “Tasmanian, I heard” – and a good pudding, before rejoining his unit in Egypt in January 1916.

“The news that our boys were off Gallipoli came as a shock of relief to me, and I think to all of us, for we dreaded going back,” he wrote of the evacuation of the troops.

“I would not be surprised if the war finishes by August. I think they are feeling the pinch alright in Germany. We will live in hopes of better things next year. Remember me to our friends ... I remain your loving son, Bert.”

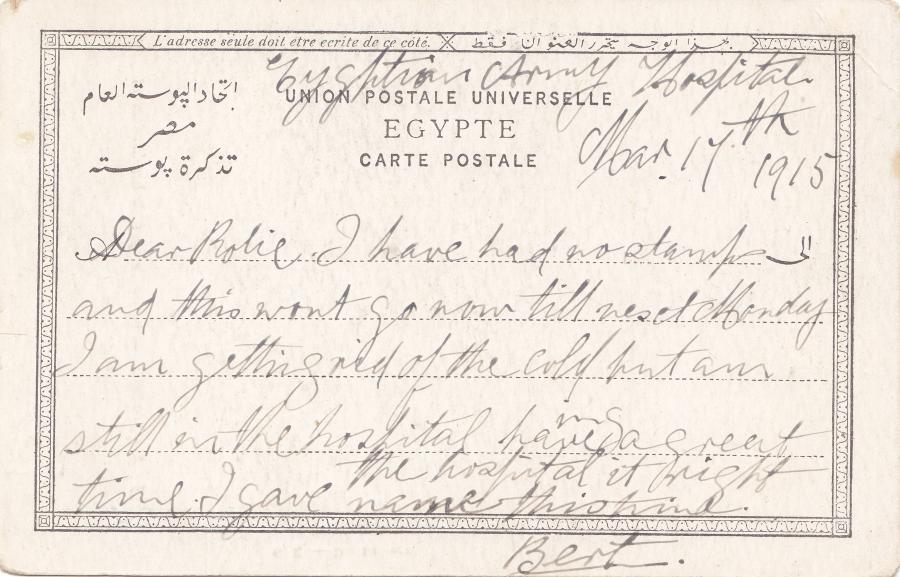

Gilbert had been hospitalised in Egypt suffering from a bout of influenza ahead of the Gallipoli landings. He wrote to his younger brother, Roland, in March 1915.

Gilbert sent this postcard to his mother from Bournemouth in October 1915 while recovering in England after being wounded at Lone Pine. Photos: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Gilbert sent this postcard from Weymouth Depot in December 1915. Photos: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Shortly after, Gilbert was transferred to the newly established 52nd Battalion as part of the “doubling” of the AIF.

He wrote again to his mother from France in July 1916.

“Dear Mother,” he wrote. “Just a few lines before we take part in the big push... We had a long march yesterday. We seen a certain great General ... He seemed a fine man... We march again tomorrow. I must close now. We hear church bells ... and the roar of the guns as well. Your loving son, Bert.”

The battalion was camped near the French village of Toutencourt, and the long march refers to a 21-kilometre trip from Halloy les Pernois to Toutencourt via Val de Masion and Puchevillers. The “certain great General” was Major General Herbert Cox, the commander of the 4th Australian Division, who inspected the troops and was less than impressed with the discipline of the Australians. The sounds in the distance were from the fighting at Pozières.

The following day the battalion marched to the village of Herrisart and eventually on to Mouquet Farm, where it took part in its first major battle on the Western Front. There the battalion played a key role in extending allied control of Pozières Ridge, but suffered heavy casualties, amounting to 50 per cent of their fighting strength. Gilbert was fortunate to survive.

Gilbert's postcard from Toutencourt, France, July 1916. Photos: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

He went on to serve during the battle of Noreuil in April 1917, before moving to the Ypres sector in Belgium, where he took part in the fighting at Messines in June, and at Polygon Wood in September, as the allies attempted to capture the high ground along Passchendaele Ridge.

He wrote to thank a Miss Jones, of the Epsom State School in Victoria, from Flanders.

“Dear Edna,” he wrote. “Just a note thanking you and your schoolmates on behalf of myself and our battalion headquarters for the gifts of socks, shirts, etc., sent last year, and only received by us to-day. They were none the less appreciated as they were quite all right. We are having a good, quiet time now, but we have been through some very heavy fighting... Wishing you all good luck from G. C. Toplis."

After a period of leave in England, Gilbert returned to France, just in time to take part in the fighting at Dernancourt on 5 April 1918. Days later, the 52nd Battalion was tasked with taking back the French town of Villers-Bretonneux, which the Germans had captured from the British some weeks earlier.

On 24 April 1918, the Germans launched an attack on the Australian positions using gas, tanks and armoured vehicles. The 13th and 15th Brigades were tasked with encircling and clearing the village and Gilbert and his mates faced heavy machine-gun fire as they made their way towards their objectives.

Gilbert Toplis. Photo: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Despite fierce opposition, the Australians managed to secure the town by the end of the following day. Though successful, the recapture of Villers-Bretonneux had cost the 13th and 15th Brigades more than 1,400 casualties.

Gilbert was among those killed.

His comrades told his mother that he had been sniped through the head while undertaking scouting duties during the advance on the town on the 24th of April.

The battalion’s chaplain, the Rev. D. B. Blackwood, later wrote to his mother to convey his sincere sympathy for the loss of her son.

“He was a fine fellow – always so ready to help,” Blackwood wrote. “He truly gave his life, and you must be proud of him. All his mates thought a great deal of him. We were able to give him a decent burial on the battlefield, and a memorial is being erected near the place. The deceased was highly respected by all who knew him, his honest, manly, straightforward ways won him many friends, and he will be sadly missed by them.”

Gilbert’s burial place was lost during the ongoing fighting, but his remains are believed to have been among those that were buried in the nearby Adelaide Cemetery as “known unto God”. It was from this cemetery in 1993 that an unknown Australian soldier was exhumed and then buried in Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

A wooden cross memorial erected in memory of members of the 52nd Battalion who died on 24-25 April 1918 during the loss and recapture of Villers-Bretonneux. Photo: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

Today, Gilbert’s name is listed on the Roll of Honour and on the Australian Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, alongside the names of more than 10,000 Australians who have no known grave.

His story was told at the Memorial’s Last Post Ceremony on the 105th anniversary of his death.

For Stuart, it was particularly moving. His grandfather was Gilbert’s younger brother Roland.

“I never got to meet my grandfather, but my Dad always told stories about his Uncle Gil and his father and their relationship,” Stuart said.

“We had his medals at home and I always thought it would be fascinating to know the story behind those medals and what he did during his short life.

“There's a series of postcards that I've kept all my life that I discovered in one of the spare rooms at my grandmother's.

“They were postcards that Uncle Gil had sent back to his mum and his brother, my grandfather.

“They’re really the only insights I have into what he was thinking and feeling at the time.

Gilbert was the sole support for his widowed mother and his two younger siblings. Photo: Courtesy Dr Stuart Toplis

“I’ve since had the opportunity to visit the cemetery at Villers-Bretonneux and that was extremely moving ...

“I was the first family member to ever visit the war graves there. It’s so far away from Australia, you can’t help but think, ‘Why were these people there in the first place? What must it have been like for them?’

“It’s just rows upon rows of white headstones, many of which don’t have a name.

“You look at the ages of them – 17, 18, 19 – and you can’t help but think, why?

“These of course are the sorts of questions a lot of people have around war, but it's so apparent when you are in the fields of France, and you see all these white headstones in the middle of a paddock in the middle of nowhere.

“It was only months before the end of the war when he died and it would have been absolutely devastating for the family, in so many ways.

“My great-grandmother died about four years later and my grandfather moved to Victoria, looking for work to help support his sister.

“He named his first son Gilbert after him, and so that in itself reflects the love and respect he had for his older brother.

“There are of course thousands of these stories – Uncle Gil is only one of thousands who died – but to me, it's not about celebrating war, it's about the celebration of a life that could have been.

“He was just 28 when he was killed, so he wasn't the youngest soldier who died, but he still had a lot of life to live ...

“It would have been fantastic to have actually met him.”