The German Officer's Corset

This corset was worn by an unknown German officer on the Western Front during the First World War. It was removed from him by French troops when he was taken prisoner at Dickiebusch, Belgium in 1916 and collected by Captain Louis de Tournouër, an officer in the 9th Regiment de Chasseurs who served in Marshal Petain's Staff in 1915-1916.

Corset taken from a German prisoner of war by French troops in Belgium, 1916.

Men’s corsets

While better known for being a female fashion staple, men also wore corsets throughout the centuries. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries they were particularly popular with officers in armies with great martial pride and very showy, and often tight, uniforms. Although it was not unusual for officers in various armies to wear corsets with their uniforms, at the same time there does appear to be something of a stigma attached to the wearing of them – particularly in the British and Australian media towards the German military. In the lead up to and the early stages of the First World War there were various representations of the German military as foppish dandies.

In 1910, an article described “Some German Types”, including “The Officer”. Among other disparaging comments and clichés were “Stiff, square-shouldered, with his waist imprisoned in corsets, a monocle stuck in his eye by way of adornment, and his moustache with its pointed ends upturned as though to threaten the skies, he exactly typifies the German conception of elegance…he gives you an impression of priggishness, of a man who thinks that everyone must admire him.” (Northern Argus SA, 11 Feb 1910).

In the early months of the First World War the German officer’s “priggishness” was again highlighted in a series of cartoons featured in Punch magazine. A piece of early war propaganda, the German officer is portrayed as vain, and to a degree feminised and so not a military threat. Among other vanities displayed in the cartoons, an officer is seen being wedged into his very tight (and female styled) corset, extolling his batman not to tighten him too much in case they have to retreat because he “..can’d run if mein corset are too tightd”.

However, it was not just German officers that wore corsets. A 1901 newspaper article noted a court case in Paris where a corset company reported that one of their branches made corsets for men. They made more than 18,000 in one year for men in France and also exported 3000 to England. They previously had a large number of German customers but this was reduced when a rival Berlin firm offered cheaper corsets. Even in Australia and Britain corsets for men were not a completely alien piece of undergarment to help a man look his best in his elaborate uniform. However, they appear not to have reached the same level of popularity or acceptance as on mainland Europe.

However, it was not just German officers that wore corsets. A 1901 newspaper article noted a court case in Paris where a corset company reported that one of their branches made corsets for men. They made more than 18,000 in one year for men in France and also exported 3000 to England. They previously had a large number of German customers but this was reduced when a rival Berlin firm offered cheaper corsets. Even in Australia and Britain corsets for men were not a completely alien piece of undergarment to help a man look his best in his elaborate uniform. However, they appear not to have reached the same level of popularity or acceptance as on mainland Europe.

19th century Grenadier Guards drummer uniform, illustrating how elaborate some uniforms could become during this period.

So why would men wear corsets? For a variety of reasons, the most obvious, as emphasised by the media, is vanity – you want to look your best in your uniform, especially in the pre-war period when they were rich with colour, glittering with gold and silver adornments and were worn uncomfortably tight.

Wear marks on the Memorial’s corset indicate it was worn so the waist was around 28 inches (71cm), about an extra small or small in men’s sizes today. At its tightest it could reduce a man’s waist to 25-26 inches (about 63-66cm) at its loosest it would be 30 inches (76 cm).

The other reason for wearing corsets or girdles was medical - it may have provided back support for the officer. There was even thought among some doctors around this period that corsets could help with intestinal problems including cramps, colic, nausea, hiccups and sore kidneys, possibly also with hernias. A similar corset marketed around this period, was the “Marvel”, advertised as a “Health Belt and Reducer”. Some were also recommended to wear while playing sport to assist in alleviating lumbago.

Treatment of prisoners

One interesting point about the removal of this corset is that it illustrates an aspect of the prisoner of war experience - vulnerability. That is, a prisoner of war is reliant upon their enemy, now captor, for their health and wellbeing. This was recognised in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, that covered the treatment of prisoners of war in such aspects as housing, food, clothing, labour, pay, religious observance. It included among the articles that “All their personal belongings, except arms, horses, and military papers, remain their property.” In other words, outside of weapons, horses and any military documents they had on them, all other items should remain within the custody of the prisoner – that their personal belongings not be looted.

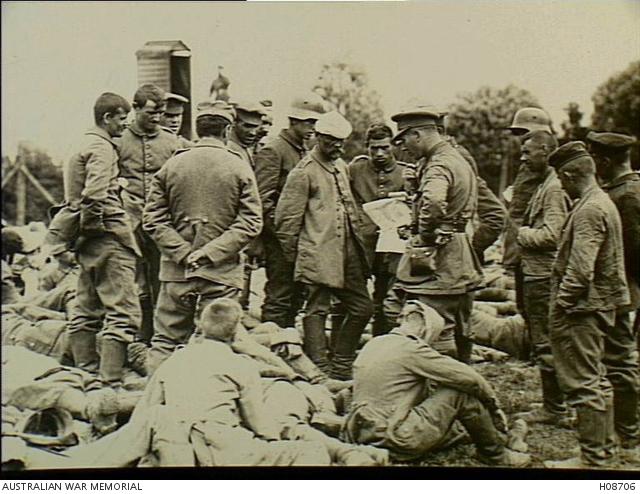

German prisoners of war in Belgium 1916.

In this instance, the officer would have had to have been stripped down to his undergarments for the corset to have been discovered and taken. Presumably the German officer’s uniform may not have fitted quite so well afterwards and other items may also have been taken from him as souvenirs. Despite the Hague Convention, taking personal items from prisoners by either side was a common occurrence. Many Australians came home with German personal items and pieces of uniform taken from their prisoners as souvenirs - pickelhauben (German leather helmets) were particularly popular.

An Australian soldier wearing a German pickelhaube while shaving. The leather satchels were also captured from the Germans.

We do not know who the officer was or what happened to him after his capture. But when the Hague Conventions were written, the experience of warfare of the late 19th / early 20th Century was their guide and no one could have conceived of a war of the magnitude of the First World War. By about March 1917, France alone held over 200,000 prisoners of war, mostly German, along with a small number of Austro-Hungarians, in addition to tens of thousands of civilian “enemy” internees. French prisons were often spartan and sometimes prisoners suffered excessively from cold, insufficient food and harsh treatment but for the most part they were treated within the conventions. In 1917 there were 90 regular camps, 17 of these were for officers and it is likely this officer found himself in one.

So while this corset was taken by a French Captain, how did it end up at the Australian War Memorial?

The deTourneour family

This corset was donated by Gontran de Tournouër to the Memorial in 1928. Born in France in 1885, Gontran was the son of Louis Marie Maurice de Tournouër and Marie Cecile Laffitte. The de Tournouërs were members of the French nobility and Louis was the heir to the family title. Gontran’s parents were divorced and he accompanied his mother and siblings, René, Roger, Jean and Odette to Australia in 1904 when he was 19 years old. His older brother, Jacques remained in France. Their mother remarried within days of arriving in Australia to a William Miller.

Gontran married Helen Waraker in Queensland in 1909. In 1914 he enlisted in the AIF. His brothers, Jacques, René and Roger (and possibly Jean) enlisted in the French Army as did their Father. Roger had tried to enlist in the AIF but was rejected so travelled at his own expense to France and enlisted there.

René, Jacques and their Father died during the war while serving in the French Army. Jacques was the heir of the family title after their Father, so upon his death in 1915, Gontran became next in line. Their Grandfather was still living but he died in December 1916, just before their Father, Louis died on 1 January 1917. Louis never received the notification of his Father’s death and elevation to the family title of Comte. Upon his Father’s death in 1917, Corporal Gontran de Tournouër of the AIF became Comte de Tournouër.

René, Jacques and their Father died during the war while serving in the French Army. Jacques was the heir of the family title after their Father, so upon his death in 1915, Gontran became next in line. Their Grandfather was still living but he died in December 1916, just before their Father, Louis died on 1 January 1917. Louis never received the notification of his Father’s death and elevation to the family title of Comte. Upon his Father’s death in 1917, Corporal Gontran de Tournouër of the AIF became Comte de Tournouër.

Gontran, Roger, Jean (who became known as ‘John’) and Odette continued to live in Australia after the war. They all lived in Queensland but Gontran suffered from ill health after the war and was advised by doctors in 1928 to move to a cooler climate. He contacted the Memorial offering some of his Father’s uniforms and this corset for donation. He also enquired if there were any jobs going at his current level as he had expertise in languages. He did not end up making the move to a cooler climate and died in Queensland on 13 July 1929.

When the Memorial was offered the corset in 1928, the Director John Treloar noted to a colleague that “I think this would be worth exhibiting as I have noticed that exhibits of this frivolous nature appeal to visitors”. He wasn’t wrong, being a man’s corset it does have a novelty value and does appeal to many people for that reason – not just the visitors but staff here at the Memorial as well. While certainly at first glance it may appear a frivolous item, as I have shown above there is far more to this corset than meets the eye. It illustrates aspects of the history of men’s health and fashion, the prisoner of war experience and it tells the story of an immigrant family in Australia in the early 20th century and I for one am very pleased it ended up a part of the National Collection here in Australia.