The songs of war

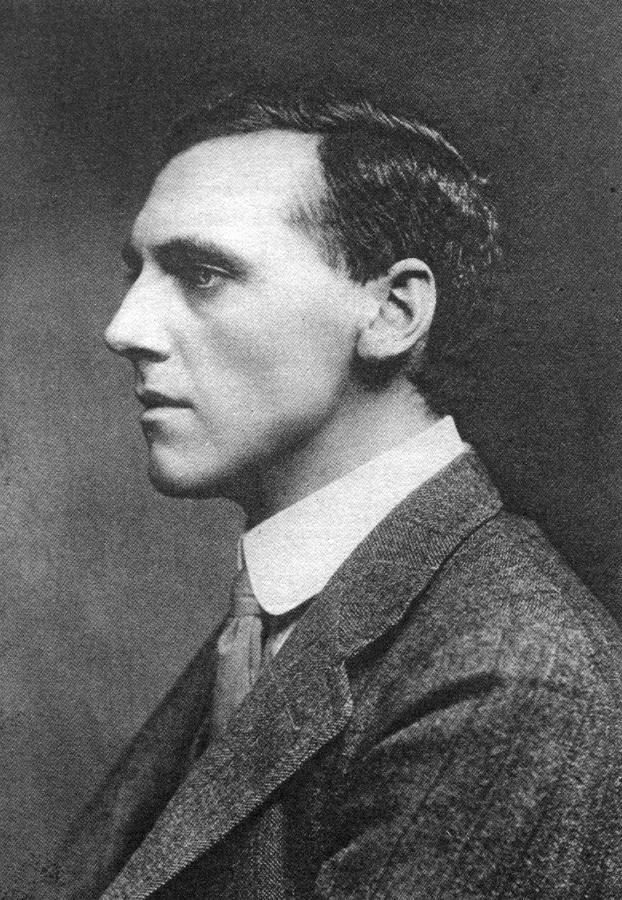

F.S. Kelly was a decorated soldier, Olympic gold medallist and celebrated musician and composer.

He was one of the last officers to be evacuated from Gallipoli, and was killed in the final days of the battle of the Somme, but amid the horror of the First World War, Frederick Septimus Kelly always found beauty and comfort in music.

A decorated soldier, Olympic gold medallist and celebrated musician and composer, Kelly wrote music in the trenches of Gallipoli and in his dugout on the Western Front, his friends often laughing at his habit of wearing gloves to protect his pianist’s hands.

His compositions though were largely lost and forgotten until recent times, but the Australian War Memorial’s musical artist-in-residence, Chris Latham, is determined to change that.

Kelly’s work has been recorded as part of the Flowers of War project and features in The Lost Jewels, a concert program of lost musical treasures that Latham unearthed to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War. Kelly’s work, the Somme Lament, which was written in the basement of a bombed-out house in Menil-Martinsart in France just two weeks before his death, also features in a program called The Diggers' Requiem.

“Frederick Septimus Kelly was one of the great cultural losses of the First World War. But as an Australian who had largely studied and worked in England, he fell between two stools, claimed by neither country, his music largely unknown,” Latham said. “He was a composer of undeniable genius … and in the coming years, it will become clearer just what kind of talent we lost.”

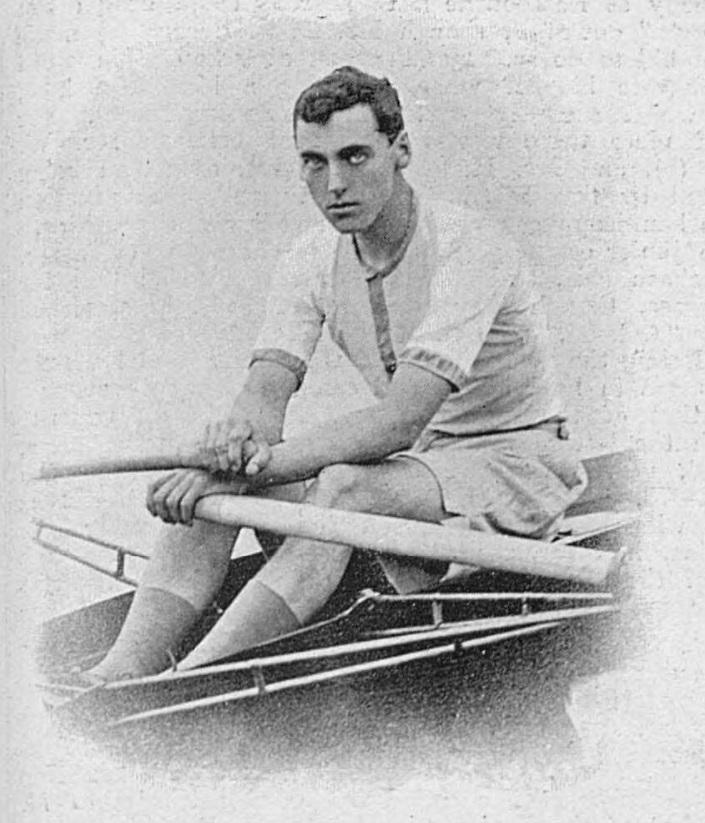

Kelly was one of the best amateur rowers of the time, winning a gold medal in the 1908 Olympics.

Frederick Septimus Kelly was born into a wealthy family in Sydney in 1881, and went to England when he was just 12 years old to attend Eton College for specialist tuition. He later studied at Oxford, and in Frankfurt, and went on to become one of the best amateur rowers of the time, winning a gold medal in the 1908 Olympics; but his real love was music. His fame as a rower meant the public saw him as an athlete who dabbled in music, but for Kelly the opposite was true, and he devoted his time to becoming a well-known pianist and composer of immense talent and skill in London.

“Kelly was unusual in that he would not write down his early drafts,” Latham said. “He would compose his works in his head, polishing them until they were perfect. As with Mozart, the pieces seem to come into being, perfectly formed, as if they had always existed. When he was killed in 1916, he had over two hours of music composed and stored in his head, which he didn’t have time to write down because of the war.”

But the person who knew ‘Sep’ best was his brother, Bertie Kelly. An amateur violinist and founding member of the Sydney Symphony himself, Bertie couldn’t remember a time when his brother actually learned to play the piano.

“I can remember him as a baby climbing onto a music stool and imitating of the actions of a pianist,” Bertie later wrote. “He seemed to pass in one bound from the stage of a boisterous child using the piano as a toy, to that of a miniature musician. He just seemed to play it as a duck suddenly finds it can swim. From the very beginning his performances were pleasant to listen to; they soon became a source of delight and astonishment to all our friends.”

Frederick Septimus Kelly was often seen as an athlete who dabbled in music.

But Septimus Kelly’s idyllic childhood – spent sailing on Sydney Harbour, swimming at Bondi, and rowing at Eton – came to a crashing end with the deaths of his beloved older brother Carleton and his father Thomas Kelly in 1901, and his mother Mary the following year.

“By then Sep was 21, and this great shock can be seen in the gaunt hollowness of his eyes which caused him to hate being photographed,” Latham said. “In the very few mature photographs that exist, his eyes are marked by a shocking blankness born of deep world-weariness.

“It is the face of the genius boy saddened and wary. He buckled academically under the weight of this grief and only just passed his degree at Oxford. His early songs from this time are miniature elegies that speak of death and dying.”

After winning a gold medal for rowing in the eights at the 1908 London Olympics, he devoted his time to music, writing in his diaries of his desire to become “a great composer”. He was “bursting with ambition to become a great player”, and in March 1909, Kelly met Jelly D’Arányi, a Hungarian violin virtuoso, for whom he would later write music in the trenches on Gallipoli.

“Kelly and Jelly made a powerful musical connection and performed together as often as they could during this period,” Latham said. “He saw her as a younger sister, so there's this very warm feeling towards her; but she's totally smitten with him.”

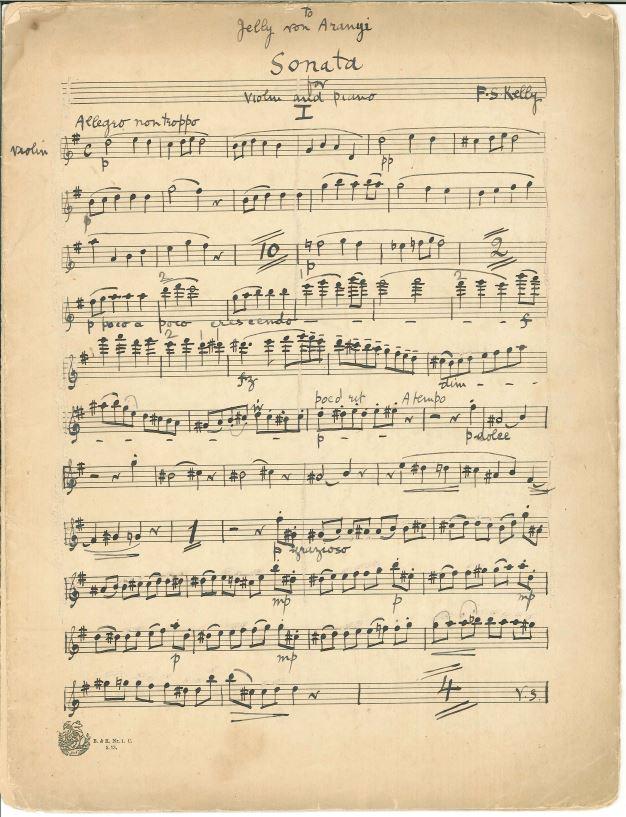

Kelly worked on a violin sonata for Jelly D’Arányi. Jelly kept the manuscript copy and Chris Latham found it in her music library.

Kelly composed a number of very fine songs during this period, but most of his songs were written for his beloved sister Maisie, with whom he lived on the weekends at Bisham Grange, on the banks of the Thames, where he loved to row. “She called him ‘Bootface’ and clearly loved him,” Latham said. “Like Kelly, Maisie was also a fine pianist and singer whom Sep would use to try out his new compositions. He would dedicate his first published song, Shall I compare thee? Opus 1, number 1, to her… [And] after Sep’s death, it was Maisie who would receive his pack containing his kit and all his belongings. She could not bring herself to open it for almost 20 years.”

Kelly had rushed to sign up when the First World War broke out in 1914. He was commissioned as an officer with the Royal Naval Division, becoming part of the famous ‘Latin Club’, a group of officers of the Hood Battalion. Among them were the poet Rupert Brooke, the composer William Denis Browne, the British Prime Minister's second son, "Ock" Asquith, and the New Zealand adventurer Bernard Freyberg, who was later commander of the New Zealand forces in the Second World War and the first Governor General of that country to have been brought up in New Zealand. The war would take all of them except Asquith, who lost his leg, and Freyberg, who was wounded seven times, eventually dying from one of his wounds when it ruptured 50 years later.

As they left for Gallipoli together, Kelly himself feared he would be killed before he could finish his work. “I am anxious to leave my unpublished work as far as possible ready for the press,” he wrote in his diary. “Unfortunately there is no time to notate the works in my head.”

Kelly was “oppressed with the sense of loss” after the death of his great friend, the poet Rupert Brooke.

Kelly was devastated and “oppressed with the sense of loss” when his great friend, the poet Rupert Brooke, died after developing septicaemia from a mosquito bite while en route to the Dardanelles. Brooke died on a French hospital ship off the Greek island of Skyros and was buried in an olive grove on the island just days before the Gallipoli landings. Brooke had written ‘The Soldier’ – “If I should die, think only this of me: / That there’s some corner of a foreign field / That is for ever England” – and Kelly was determined to remember him, his death having left “a deep and grave impression”.

Almost immediately, Kelly began composing his Elegy for Rupert Brooke, which was largely written during his time on Gallipoli. It was on the Turkish peninsula that Kelly was wounded twice and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions.

“There is a very active body of snipers somewhere up by the firing line and the whole of the afternoon bullets have been whistling continuously over my dug-out,” he wrote. “Ever since the day of Rupert Brooke’s death, I have been composing an elegy for string orchestra, the ideas of which are coloured by the surroundings of his grave and circumstances of his death.”

In June, Kelly was wounded in the foot and was evacuated to Alexandria, where he was able to buy manuscript paper and finally notate his Elegy for Rupert Brooke. He returned to the Gallipoli peninsula in July, and spent the remainder of the summer maintaining the Royal Naval Division’s defensive positions.

It was there that he began work on a violin sonata for Jelly D’Arányi. Jelly (pronounced Yelly) had long been requesting a concerto, but Kelly wrote to her from Gallipoli to say he had written a violin sonata in G major for her instead (now known as the Gallipoli Violin Sonata).

“I began composing it about three and a half months ago and I have now about half of it written down,” he wrote. “You must not expect shell and rifle fire in it! It is rather a contrast to all that, being somewhat idyllic.”

But Gallipoli was anything but idyllic. In December, he wrote in his diary how he “very nearly came to an end” one morning. “I was talking … when a shell pitched in a dugout ... about 35 yards away,” he wrote. “We went along to lend assistance to a few men who were wounded and, as we stood there, a second shell exploded a couple of yards away from me, blasting me with stones and earth – which stung like blazes. By chance, I only received a scratch on my neck.”

After the evacuation of Gallipoli, Kelly enjoyed a brief respite in London, before his division was moved to France in May 1916. It was stationed in the Souchez sector, where Kelly was put to work improving the Hood Battalion band, famously performing Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture so that the climax coincided with a dawn artillery barrage.

When the Royal Naval Division was transferred to the Western Front, Kelly continued to compose music: his last work was completed a fortnight before his death in the final phase of the battle of the Somme. “The German line is about three hundred and fifty yards in front of us,” he wrote ahead of the battle at Beaumont-Hamel. “I spent an hour and a half after dinner reading the notes as to enemy dispositions, dugouts, machine gun positions, etc. on our front and flanks and looking at the map references. It was not reassuring reading.”

Weeks later, he set out to see for himself near the town of Mesnil. “The land … is an indescribable scene of desolation,” he wrote. “For acres and acres (as far as one could see) there was no sign of vegetable life, just a sea of lacerated earth, with here and there the traces of a former trench system. The presence of these former communication trenches was confirmed by the corpses – some of them horribly mangled and with glazed eyes, others trodden almost out of sight into the mud.

“Though I was quite callous – as everyone appears to be at the front – I was haunted by the sense of terrible tragedy – the triumph of death and destruction over life. Why is it that such a terrible scene does not touch the depths within me the way a great poet would do? It seems Art goes deeper than reality.

“There were no trenches to speak of – just tracks from shell hole to shell hole. The ground was newly won and no one knew the way about the featureless wilderness. ... I cut my finger badly on a jagged piece of shell, but luckily found some iodine in my pocket.”

Despite the horror, Kelly still saw beauty where he could. “As we returning they were shelling Mesnil and as we came down the river two big shells pitched in the water and made lovely fountains,” he wrote. “The river marshes are beautiful in spite of the desolation, and are filled with moor hens.”

Kelly's Somme Lament will be played as part of Diggers’ Requiem in October.

It was amid the devastation of the Western Front that Kelly finished his Elegy for Rupert Brooke and composed his last completed work, a slow lament. “The score is in his perfect handwriting, containing not a single correction or error, not a single blemish, neither from dirt nor soot,” Latham said. “It seems impossibly clean and new.”

But Kelly had a sense of foreboding. The night before the attack on Beaumont-Hamel, Kelly’s No. 2, Lieutenant J.H. Bentham wrote that “Kelly seemed insistent that he would not survive.”

Just 15 minutes before they left their trenches, Kelly met his friend Bernard Freyberg who had served with him on Gallipoli. “We had been daily companions for the last two years,” Freyberg wrote. “I wanted to take both his hands and wish him ‘God speed’ but it somehow seemed too theatrical, so instead we talked awkwardly and synchronised our watches.”

Kelly would not survive the battle. He was killed on 13 November 1916 at the age of 35 while leading an attack on a German machine-gun position at Beaucourt-sur-Ancre.

“The situation was critical,” Freyberg later wrote. “Hesitation would have endangered the success of the whole attack on our front. Kelly, being an experienced soldier, knew this quite well, as he must have known the risk he was taking, when with the few men he had hastily gathered, he rushed the machine gun. A few men reached the position, but Kelly, with most of them, was killed at the moment of victory.”

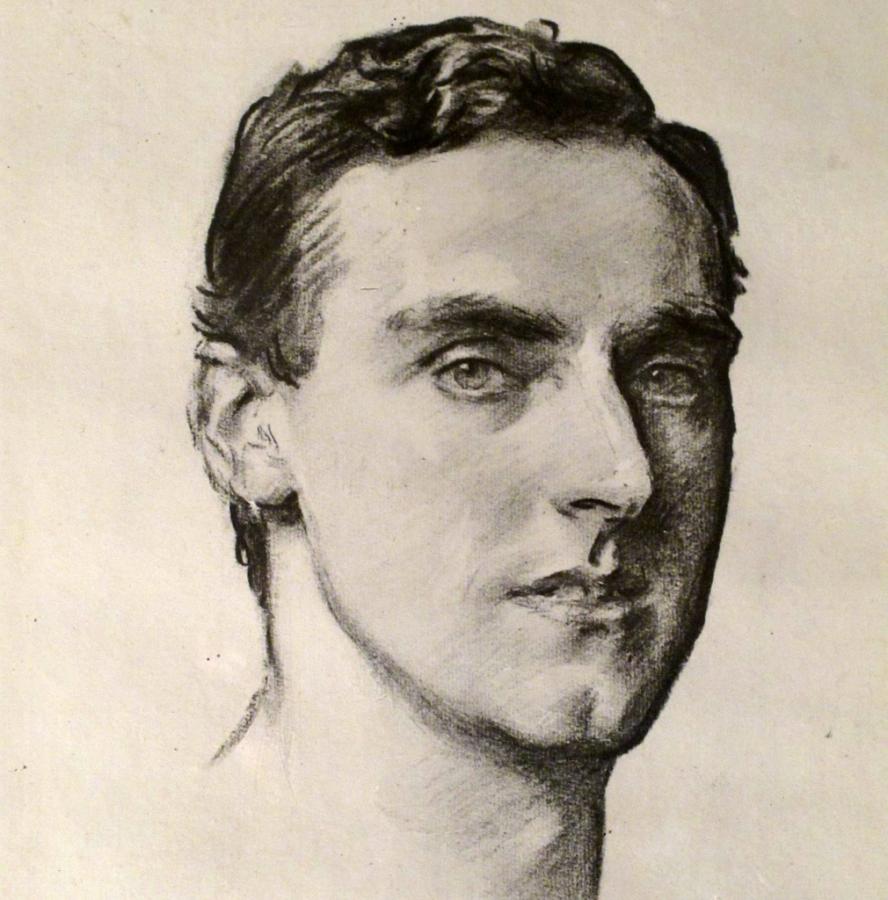

Frederick Septimus Kelly: "He was a rare and beloved creature."

Of the 25 officers and 535 other ranks, four officers and 250 men answered roll call at the captured objective that day. Freyberg was wounded four times in the space of 24 hours and was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. Kelly’s surviving men carried him back through no man’s land as a sign of respect so he could be properly buried. His grave is in Martinsart’s British Cemetery, and his men are buried nearby in Hamel, where they fell.

Freyberg later wrote: “God how we miss Kelly … he was a rare and beloved creature.” But for Latham, the most eloquent expression of the loss of Kelly would come from Jelly D’Arányi.

“It is clear that while Kelly loved Jelly’s playing, she was smitten with him as a man, and her deep love for him endured throughout her life,” Latham said. “She had wished that he was her fiancé and later told people that he was, although that would have been a surprise to him. After his death, she wrote of how he came to say goodbye to her. She woke to hear him playing the opening tune of the violin sonata he had written for her, like a beginner – Kelly didn’t play the violin – coming from afar, as if over a large body of water. She would die, unmarried, with his photograph on her piano, constantly looking back at her.”

To Latham, Kelly’s story, like countless others during the war, is something of a modern-day Greek tragedy.

“One can only speculate what would have happened if Kelly had lived,” Latham said. “Had he returned to Australia, he would have likely risen to be the Head of Music at the ABC or perhaps at the Sydney Conservatorium. The loss of Kelly and similar talents from his generation too often are stories we don’t know. If we did, we would not be so quick to risk war again. It is well past time for us to understand just what kind of talent was lost when Kelly was killed, but all we have left is the chance to get to know him through his music, as Kelly himself foresaw when he quoted Callimachus in the foreword to his Elegy for Rupert Brooke: ‘Still your works live on, and Death, the universal snatcher, cannot lay his hand on them.’”

Visit www.theflowersofwar.org