Forget me not

It’s a striking portrait of a young man about to head off to war. He stares straight at the camera, the words “Forget me not” carefully painted on the reverse of the intricate glass frame. Sadly, no one knows who he is.

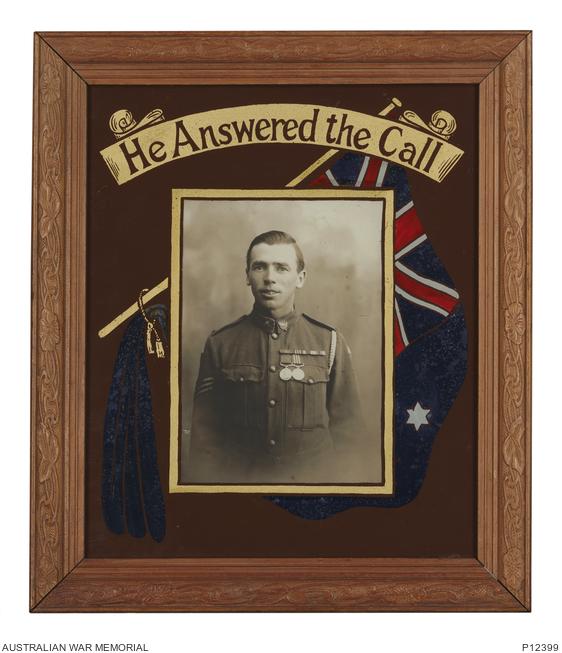

His portrait is one of 13 rare and fragile portraits on display in Framing memory, an exhibition of reverse-painted glass framed photographs at the Australian War Memorial.

Curator Joanne Smedley hopes the exhibition will help identify him.

“It’s a bit of a mystery,” she said. “We know his photograph was taken by the Crown Studios in Sydney, but the Crown Studies suffered a catastrophic fire in 1918 that destroyed their negatives and their records, so I don’t know if we’ll ever find out who he is, but I hope so.”

The Memorial holds the largest-known collection of these rare and fragile reverse-painted glass framed portraits. This exhibition is the first time 13 of them have been on display together. A fourteenth portrait is on display in the First World War Galleries.

“They’re very personal memorials, and that’s the thing that is quite striking about them,” Smedley said.

“They are beautifully framed portraits of soldiers that have been framed in the most unusual way, and when you see them all together you just get a sense of the differences and the styles.

“The surrounds, which are quite colourful, include flags and floral emblems, such as waratahs, forget-me-nots and flannel flowers, that have been painted on the reverse on the glass that covers the portrait.

“The colours are just so luminous because they are painted on glass, and they’re all a little bit different, which is why I think they’re also quite charming.”

Sapper William George Hallett enlisted in July 1917and died of broncho-pneumonia on 18 October 1918.

Patriotic framing evolved throughout the First World War into decorative and personalised products as studio photographers and businesses sought to stand out from their competitors.

“They were created in a time when colour photography on paper wasn’t technically possible, so studios had various techniques to make them look more realistic,” she said.

“Some have been quite heavily hand-coloured to give a more life-like feel, but it’s not until you look closely that you wonder how on earth these were done, and you can see that they’re created with this really unusual technique of being painted in reverse on the back of the glass.

“The technique of painting on glass is something that has been done for centuries in Europe … but this kind of matting is quite unique.

Private Wallace Benjamin (Wal) Giffin enlisted on in March 1916 and was killed in action at Peronne on 1 September 1918, aged 21.

“We’ve never really seen it anywhere else. They seem to have existed only for the First World War and are full of symbols that would have made sense to people who would have grown up with the language of flowers from Victorian times.”

The actual maker of the frames is unknown, but Smedley believes the use of waratahs and flannel flowers indicate they were operating in Sydney.

“That struck a bit of an alert for me,” she said. “When you look at the backs of many of the frames, they still have the original backing, but no makers’ names at all, so that was always a bit of a mystery.

“They often feature waratahs, which are the NSW state emblem, and flannel flowers which are from Sydney, so I felt that had to be a bit of a clue, and that led me to believe that a Sydney maker was the probable creator.”

“It’s been a great quest of mine to try and find out who created them,” she said.

“I knew technically how they were created, so I was looking for those terms, thinking that a studio was going to advertise them, but I had no real joy in finding anything.

“Quite a few have banners at the top – ‘With loving thoughts’, ‘he heard the call and answered’, ‘forget me not’ – so I searched for ‘he heard the call and answered,’ and up came an advertisement for Anthony Hordern & Sons.”

Private Francis George Clark enlisted in February 1916 and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and Military Medal during his service in the First World War. He enlisted in the Second World War and was killed in action at Tobruk on 7 June 1941, at the age of 49.

Anthony Hordern & Sons was a major department store in Sydney and had a framing studio in Redfern. They released a catalogue each year and had a stand at the Royal Easter Show.

“It was listed as patriotic frames, and I started getting a little bit excited at that point,” Smedley said.

“They listed various sizes for different sized photographs, from postcards to cabinet cards to Paris panels, and also had flags painted on glass, so I thought, ‘Is this my holy grail?’”

She is now trying to track down a 1918 or wartime period Anthony Hordern & Sons catalogue to help confirm whether the store was involved in the sale of the items.

“I can’t absolutely say that this is where the origin is,” she said. “But it seems to tick quite a lot of the boxes.”

For Smedley, the portraits are particularly special.

“I’ve been a bit of a quiet fan ever since the first came one into the collection,” she said.

“A couple from country New South Wales said they were bringing a portrait in and when they arrived in the office, they had an object wrapped in a blanket. When they opened up the blanket, we were all just so taken by it.

“They are not high art creations, but they are artistic, and each one tells an individual story.”

Gunner Ronald Frederick Eedy enlisted when he was 18 years old.

Gunner Ronald Eedy’s story is particularly poignant. He was 18 years old when he received his father’s written permission to enlist in March 1915.

“His letter of permission is probably one of the most beautiful letters of permission I have ever read,” Smedley said. “He has quite a youthful face, and when people wander through and see him, they say, oh, because he really looks like a 15 year old boy.”

Ronald’s father, William, and three brothers, George, Peter and Neil, had already enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force when he wrote asking for permission to serve in the AIF.

“Well my dear boy,” his father wrote. “I can understand your feeling that you would like to join your brothers, who are already in Egypt on active service now. To business, my dear Ronald, you have my full consent. Knowing that you would be a credit to any company of soldiers and your past experience as an officer in the compulsory would stand you in good stead and fit you for the trials & hardships that you would have to face then at the front.”

Ronald sailed for Egypt in May 1915 and went onto serve on Gallipoli and the Western Front. He was killed in action in October 1917 at Zonnebeke, Belgium, at the age 20. His father and brothers all survived the war; his portrait a poignant reminder of the son and brother they had lost.

Brothers William and Samuel Anderson enlisted together during the First World War.

William and Samuel Anderson also served during the First World War. Their photographs are framed together, side-by-side, under the banner “for king and country”.

“They were two young brothers who enlisted together in July 1915 at the ages of 18 and 21,” Smedley said. “They were given consecutive service numbers and served in the same unit on the Western Front … They’ve scraped the paint off the sides of the glass to fit both photographs in the frame.”

Both were awarded the Military Medal for gallantry for their actions during the battle at Mont St Quentin in France. William for rallying his platoon when his commanding officer was wounded in action and Samuel for taking charge of his platoon when his officer and sergeant were both wounded.

“It’s curious to think that quite possibly they never talked about it,” she said.

“In the 1960s, William wrote to the Department of Defence to ask for some information relating to the places where he had served because he was planning to go back to the battlefields, but also to ask why his brother received his Military Medal.”

Both brothers had survived the war, but many of the others featured in the exhibition were not so fortunate.

Private Percival Luck was reported missing in action on 25 January 1915.

Private Percival Luck was born in Wartling, East Sussex, and served as a reservist in the United Kingdom before immigrating to Sydney. He married Edith Snoad in 1913, and their daughter Gwendoline was born the following year. When war was declared in August 1914, Luck was recalled to England.

“He hadn’t been in Australia long, just long enough to get married and have a daughter,” Smedley said. “So I think the portrait is a really lovely connection back to a man who looked for a new life in Australia, but was recalled to England to serve with his regiment.”

After taking part in the battle at La Bassée, Luck was reported missing in action on 25 January 1915. He was 27 years old and has no known grave.

Private Harold Murray stands proud, his arms behind his back, above the words, “My brother is fighting for his King and Country”. A wool wash labourer from Sydney, he enlisted in June 1916 at the age of 18.

“His story is quite sad,” Smedley said. “His parents’ marriage had broken up, and he and another brother went to live with their widowed sister, Florence. She had three children she was supporting, so their wages went to helping and supporting those young children as well, and I think their financial support probably helped her a great deal … but Harold’s story is not a happy one. He is killed in action at the battle of Polygon Wood in September 1917.”

Despite Florence being named as his next of kin, his father made numerous claims to the Army Records Section to be recognised as his legal next of kin, and later received Harold’s medals and Memorial Scroll. The portrait was purchased by his sister.

Private Harold David Murray enlisted in June 1916.

“You can really sense her desperate straits in her letters in his service file,” Smedley said. “And this portrait is a proud reminder of his service.

“When you start looking at the objects you get a sense of how these people were honoured, and I think that’s part of the unique nature of their framing, and the stories that they tell.

“Ever since the first one of these beautiful works came across our section, I’ve just been so intrigued by them.

“Their framing is just so luminous and so different to anything else that we have had from that period of time.

“They tell the story not only as an object, but also as a portrait of the person involved, and I just love the way those two things come together in such a charming and decorative way.

“They all tell their own stories, and it’s a privilege for us to be able to tell these stories.”

Framing Memory is on display in the Captain Reg Saunders Gallery at the Memorial until 2 July.

Join curator Joanne Smedley and conservator Janet Hearne for a free public talk at the Memorial on 27 June 2019 to hear about how the exhibition was put together, some of the conservation required for these fragile objects, and how the framing adds to the stories of the soldiers pictured. For details, view the Framing Memory event.

Framing Memory also features in episode six of Louise Maher’s podcast series, Collected: stories from the Australian War Memorial. To listen, view the Collected podcast page.

A hairdresser from NSW, Private Robert Groves enlisted in August 1915. He was awarded the Military Medal in October 1916 and was killed in action in Belgium in September 1917.