‘You are just holding onto each other hoping that you don’t go overboard’

In 2012, retired Major John Milton Gillespie, a Vietnam veteran and immigration consultant, left a bequest to the Australian War Memorial to purchase works of art. In recognition of his life and work, curators decided to use the bequest to commission artist Dr Dacchi Dang to create work that explores the wartime experience of Vietnamese–Australians and its legacy today. Here is Dacchi’s story.

Photo: Janelle Evans

Dacchi Dang was just 16 years old when he fled war-torn Vietnam on a tiny fishing boat in 1982.

“I’d never seen the ocean that big, and I’d never seen water that colour,” he said.

“When you think of water you think of blue, but what you actually see is just black because that’s how deep the ocean is.”

With him were two of his sisters, one of his brothers, and almost 140 others, all crammed into an 11-metre fishing boat designed to carry four or five people.

“I remember sitting on the edge of the boat – and when I say edge, I mean edge,” he said.

“You just put your hand out and you can touch water. The waves are way, way, way above your head, and that’s how bad it is.

“You see how powerful the waves are and how powerful nature is; you are just holding onto each other hoping that you don’t go overboard.”

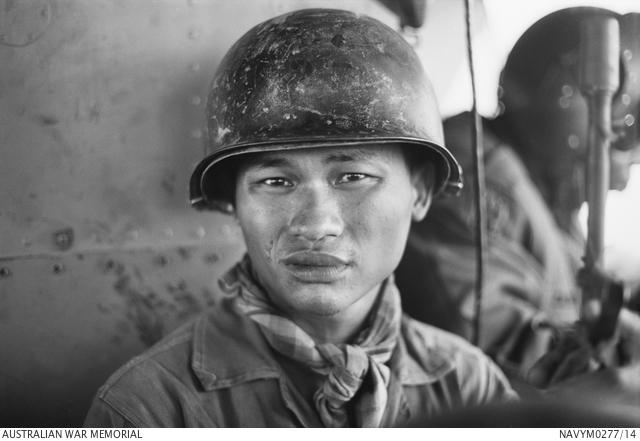

A member of the 9th Army Republic of Vietnam sits in an Iroquois helicopter, ready to be inserted into a search area.

Born in Saigon in 1966, Dacchi grew up in a Chinese–Vietnamese family and witnessed the final days of the Vietnam War as a child.

“My family ran a photographic studio and people would come to our studio to have their portrait done,” he said.

“But we lived not far from the airport and we would see the aeroplanes and the choppers and all of those kinds of thing.

“I remember I was sitting on the balcony watching South Vietnamese soldiers heading to the front line, and then there were the helicopters basically surrounding the whole sky.

“You basically just grew up with all that. The soldiers, and the police, were everywhere, but as a little kid, you’re not actually aware of what it all means.

“In the city itself, it was just intense. I remember the students and the demonstrations; they got crushed by the police, and the whole city got blocked out for a few days … The police just basically tried to arrest as many as they could.

“As a kid I was probably unaware of the chaos, but when you grow up with that sort of thing it’s just part of life.

Vietnamese infantrymen, along with their two Australian advisors who are members of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV), board a US Army helicopter for a combat assault into enemy territory in the northernmost section of South Vietnam in September 1970.

Troops of 1st Battalion 1RAR take up defensive positions during operations north of Saigon.

“I’ve so many visual memories of that time. I was going to a Chinese school, which was in District 5, and we saw so many soldiers …

“We were at school one day when the palace got bombed and they just said, ‘Everybody go home.’

“There were curfews and everybody was running and my parents just made sure that there was someone to pick us up to make sure we got home safe.

“Not long after there was utter chaos. The communists were getting closer and people were starting to fear that they were coming …

“There were choppers, and tanks, and soldiers, and they were basically running to the front line, but as a kid we just thought, ‘What’s all that about?’”

“People started to panic, and those pictures are still very clear in my mind.”

Phuoc Tuy Province, South Vietnam. February 1972. Cambodians at the Long Hai Training Centre in Phuoc Tuy Province, being trained by members of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV). Members of the team conducted twelve week courses at the centre to help train Cambodian battalions.

Pleiku, South Vietnam. July 1970. South Vietnamese Army Captain Siu Ddow and Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) adviser, Warrant Officer Class 2 Jim Calcutt of East Reservoir, Vic, train Montagnard soldiers at the 2nd Mobile Strike Force base in central South Vietnam. They are teaching the soldiers how to use an M79 grenade launcher.

His parents feared the worst, and did everything they could to shelter their children from the reality of war.

“My parents experienced the 1968 Tet Offensive and they knew how bad it was,” Dacchi said.

“A couple of days before the fall, soldiers were running to the front line in full military gear, and then not long after I saw a lot of them running back with no equipment …

“I got up onto the roof and was watching a chopper flying; I thought they were going to the front line to have a battle with the communists, but now I realise the chopper was actually people trying to get out of Saigon, and that it was the evacuation of the Americans at the embassy.”

He was just nine years old when Saigon fell to communist forces on 30 April 1975 and North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace.

A pedi-cab operator in Saigon is dwarfed by a convoy of American Army tanks moving through the city.

Vietnamese children watch a Centurion tank of A Squadron, 1st Armoured Regiment, in June 1970.

Seven years later, Dacchi made his own desperate attempt to escape the city with three of his siblings.

“When the war ended in 1975, I was living under the communists,” he said.

“Life was pretty tough at that time. You just couldn’t see bright future; people were suffering, and life was miserable.

“Many Vietnamese just couldn’t see a future there, so many left the country searching for new homes.

“A lot of people got their houses confiscated and they were sent to the economic zones, so basically just to do hard labour.

“In 1979 there was also the border conflict between Vietnam and China up north so the majority of the Chinese community tried to escape the country and my family decided to send some of the children out.

“Many escaped by either walking to Cambodia and through to Thailand that way or by hopping on one of the boats.

“If you got caught you would be put in prison so you were taking a big risk, but as a teenager you’ve got no fear; you just want to take that chance.

“You are just hoping that you will make it to land, and be able to search for a future, and hopefully find a safe place to live.”

He was forced to leave behind his mother and father, as well as his grandmother and three other siblings.

“It’s extremely scary, but you basically just take the risk,” he said.

“When you are actually on the boat, all you want to see is land. The waves are way, way, way above your head and all you see is black and blue.

“It’s so crowded down [in the storage hold], you feel like you don’t have air to breathe, so you just try to do whatever you can to get on the deck. Yes, up there, it is freezing cold and wet, but at least you’ve got some air to breathe.

“You basically just want the boat to land safely somewhere, so that you can put your feet on the ground, and then you will be a happy, happy, man.”

After four terrifying days at sea, Dacchi and his siblings reached Malaysia, spending nine months at the Pulau Bidong refugee camp before being accepted as refugees to Australia.

In Australia, Dacchi learnt English, finished high school, and obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Master of Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales, before completing his PhD at Griffith University.

It would be six years before he was reunited with his parents.

“Life was pretty tough for them,” he said. “They didn’t have much to eat. You would probably have one chicken for the whole family, and that’s once a year, but the rest of time you just have veggies and any other food that you can find because people can’t afford anything.”

Iroquois helicopters of No. 9 Squadron RAAF prepare to land and pick-up soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, 52nd Regiment of the 18th Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

More than 40 years after he fled Vietnam, Dacchi is still fascinated by the Vietnamese diaspora, the sense of identity as a refugee in an adopted homeland, and the experiences of veterans living with memories of the battlefield.

In 2016, he was commissioned by the Australian War Memorial to create works of art that explore the wartime experience of Vietnamese–Australians, as the relationship between Australian and South Vietnamese veterans, and the legacy of the Vietnam War.

The commission was the result of a bequest from retired Major John Milton Gillespie, a Vietnam veteran and immigration consultant who helped people move to Australia.

“This is a very important project for me,” Dacchi said. “As a little child I witnessed the last days of the Vietnam War and I saw the North Vietnamese soldiers enter the country. But many of the refugees who came to Australia were soldiers from the South Vietnamese army – the ARVN – and most never actually talk about that experience.”

Horseshoe Hill, South Vietnam. 1969-09. Corporal David Waterston shows Vietnamese soldiers of the 18th Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) how an M60 machine gun works.

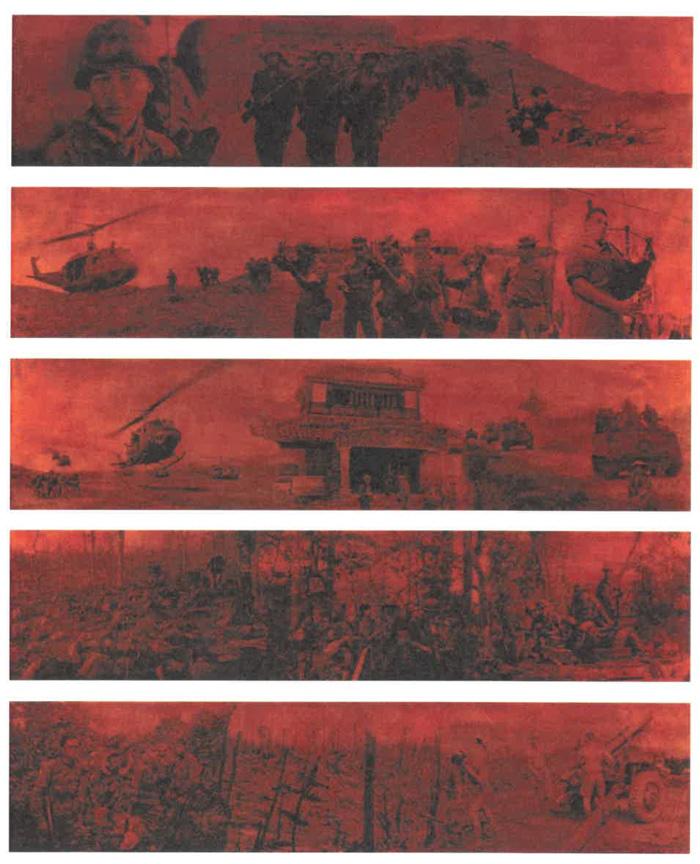

For the commission, Dacchi created two bodies of work: the first is a traditional Vietnamese lacquer painting, Brothers in arms; the second is a multi-platform stop-motion animation featuring photography, video, animation, and drawings.

“Since their resettlement in Australia, the Vietnamese veterans’ stories have largely been silent in Australian communities,” Dacchi said.

Dacchi interviewed veterans who served with Australian and South Vietnamese forces to learn more about their experiences and spent time going through the Memorial’s collection of photographs from the Vietnam War.

He selected images that resonated with the interviews he’d conducted, in some cases finding photographs of the soldiers that he had spoken to, and printed them onto plywood panels, overlaying them with lacquer using a traditional Vietnamese technique.

“The soldiers still feel trapped from their painful past and the loss of their homeland,” he said.

“To them, it is too painful to bring back those memories, and I have shared some experienced to myself. I know exactly how they feel. It also brings back a lot of my sadness.”

Dacchi Dang, Untitled, 2017, black and white digital pigment print 280 x 280mm

He returned to Vietnam in 2017 in order to research the traditional lacquer used in the commission.

“Lacquer is part of that culture and identity so the format for the work is very, very important,” Dacchi said. “The local people actually collect the sap of the tree and make that into a medium which they use to make the art; you have to build it up for many layers, and at the end what you are looking for is super, super shiny, so that it is almost like a mirror.”

As the battle of Long Tan, one of the fiercest battles Australians faced during the war, took place in a rubber plantation, the use of the lacquer derived from rubber trees is highly symbolic.

The final work consists of five plywood panels and is about four and a half metres in length. Together the panels form a long red stripe.

“The strip is basically one strip of the flag of the republic of Vietnam, so the work has a lot of symbolism and meaning behind how it's constructed,” Dacchi said.

“My aim is to create a new understanding of, and a relationship to the representation of the memories and experiences of the Vietnam War through the tales of Australian and Australian–South Vietnamese veterans [ARVN].

“I hope this work can actually bring people together to understand what their experience is … and give them a bit of an insight into how they feel, and how they see the war.”

Brothers in Arms, Dacchi Dang, 2017, Lacquer and ink on plywood, 5 panels, each: 20cm x 90cm (AWM2016.626)

He is extremely grateful to the Gillespie Bequest for the chance to share their stories.

“It’s a new perspective on how to see that conflict and hopefully through this work people will have a better understanding,” he said. “It’s provided an opportunity to have that experience, and to have that voice heard, and to reach out to the public … to help people understand their experience. It’s so important … to bring everything together, and I feel privileged to have the opportunity thanks to the Gillespie Bequest.”

Dacchi Dang’s work Brothers in arms will go on display in the Reg Saunders Gallery on 9 October 2019. To learn more about Dacchi’s commission and the Gillespie Bequest, visit here.

For information on how to be involved with the Memorial, contact giving@awm.gov.au