Fighting for Country

By Claire Hunter with Isabella Walker.

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons. It also contains racist terms and descriptions, the use of which reflects language and attitudes of the time.

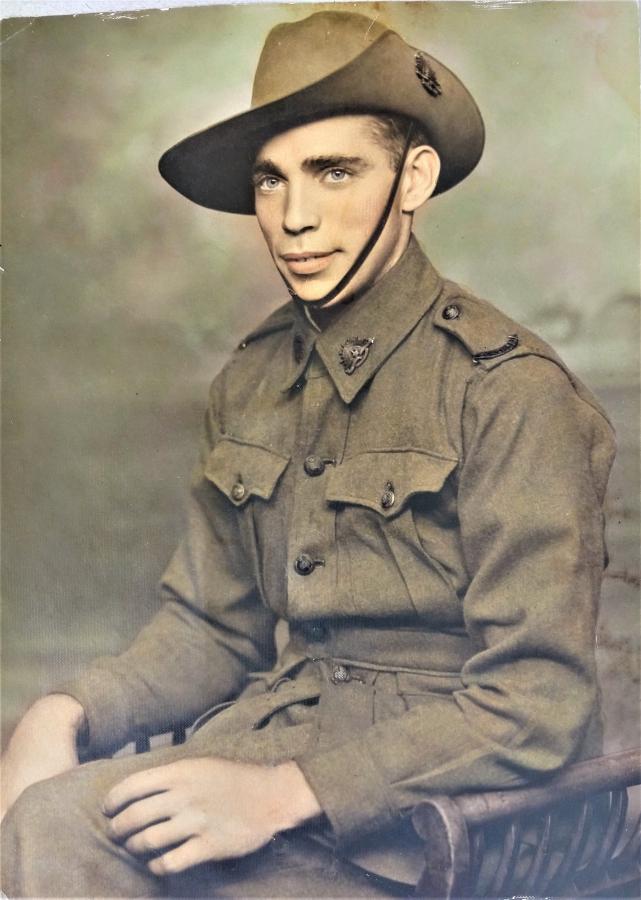

Clarence Atkinson DCM. Photo: Courtesy Isabella Walker

It was a day that would change Clarence Atkinson’s life forever: the 27th of June 1941.

The then 26-year-old was serving as a private with the 2/3rd Battalion in Syria when he made a split-second decision to charge an enemy machine-gun during fighting near Damascus.

The men of 10 Platoon had been pinned down by enemy fire from a Hotchkiss gun for three hours while attempting to hold a defensive position on the Jebel Mazar feature. One section of 12 Platoon tried to outflank the gun, despite the number of snipers, but was held up.

When the man next to him was shot in the head, Atkinson leapt into action. Armed with a haversack of grenades, he dashed forward among the rocks while coming under intense enemy fire. Pushing forward, he hurled the grenades, clearing the area of enemy and capturing the Hotchkiss gun.

He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions that day, the first known Indigenous Australian to be awarded the medal during the Second World War.

He was praised for his “amazing courage … conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty”.

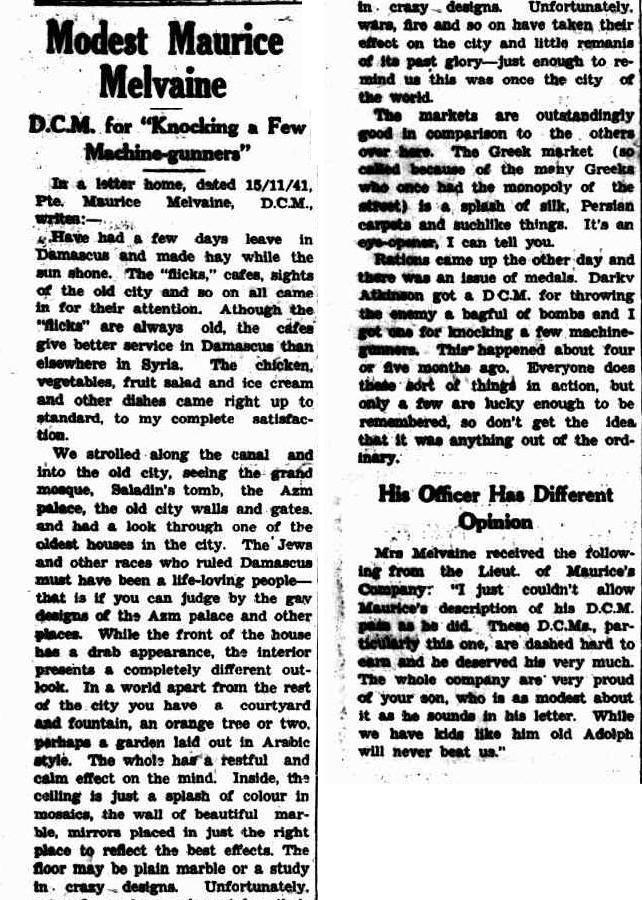

A newspaper report from the time quoted another soldier as saying, “Darky Atkinson got a DCM for throwing the enemy a bagful of bombs”.

Five years later, he was homeless.

The third child of Cecil Atkinson and his wife Eileen, an Indigenous woman, Clarence Cecil Atkinson was born in the mist of the First World War in the Sydney suburb of Kogarah, New South Wales, on 21 May 1915.

He was working as a chef when the Second World War broke out in September 1939, and enlisted shortly afterwards, leaving behind his wife Clarice and their two young children, Gwendoline and Robert.

Clarence's wife Clarice Atkinson. Photo: Courtesy Isabella Walker

His uncle, James Atkinson, had served during the First World War and three of his brothers – James, William and John – would serve alongside him during the Second World War.

He was posted to the 2/3rd Battalion and sailed for Egypt in January 1940, arriving in Kantara on Valentine’s Day.

The battalion took part in successful attacks at Bardia and Tobruk in January 1941, and headed for Greece a few months later to resist the anticipated German invasion. In April 1941, they took part in the battle of Tempe Gorge, and helped block German movement through the gorge, allowing the unhindered withdrawal of Allied forces further south. By the end of the month, they were evacuated by sea and returned to Palestine. In June and July 1941, the 2nd/3rd took part in the campaign in Syria and Lebanon and fought around Damascus in the unsuccessful attempt to secure Jebel Mazar and in the climactic battle of Damour. The battalion returned to Australia in August 1942.

Atkinson struggled when the battalion left the Middle East and faced a long list of disciplinary infringements, including three court-martials. He was often absent without leave, and in October 1943, couldn’t be found. When he reappeared with his unit in early 1944, he was court-martialled and initially sentenced to nine month’s detention.

When he was released in mid-1944, he joined the 2/14th Battalion. He was promoted to corporal in January 1945, and went on to serve at Morotai and Balikpapan.

He returned to Australia after the war, taking on a number of different jobs, working at a tip, as a concreter, and even as a bookmaker from the front room of his house, in an effort to support his young family. His wife Clarice would work in a factory when he was between jobs to help out, but it still wasn’t enough.

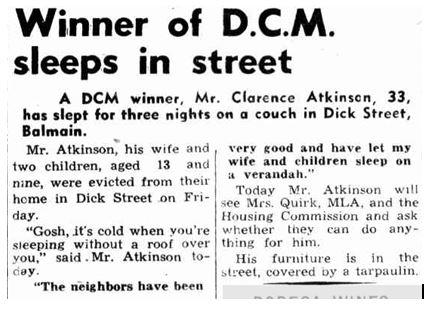

The Sun (Sydney, New South Wales), Monday 11 April 1949.

By 1949, they were homeless. Under the headline, Winner of DCM sleeps in street, the Sun newspaper reported that Atkinson and his family had been evicted from their home in Balmain. His wife, and two children, aged 13 and nine, were sleeping on a neighbour’s veranda, their furniture in the street, covered by a tarpaulin.

“Gosh, it’s cold when you’re sleeping without a roof over you,” Atkinson was quoted as saying. “The neighbours have been very good and have let my wife and children sleep on a verandah.”

The Australian War Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer, Michael Bell, said Atkinson was one of thousands of Indigenous Australians who volunteered during the Second World War.

“Despite lack of recognition as a people, denial of basic human rights and concerted efforts at exclusion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have served in all conflicts and peacekeeping involving Australian defence contingents since prior to Federation until now,” Bell said.

“When the First World War broke out in 1914, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had few rights, poor living conditions, and were not allowed to enlist in the war effort. Despite this, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people wanted to serve in defence of Australia, and were willing to change their names, birth locations, heritage and nationality in an effort to do so.

“Many who tried to enlist were rejected on the grounds of race; but many more enlisted successfully.

“They served on equal terms and were paid mostly the same rate as non-Indigenous soldiers with one notable exception, but when they returned home, they found that discrimination was still prevalent and had indeed worsened.

“When the Second World War broke out just two decades later, Indigenous Australians were still not legally allowed to enlist, yet many did so, but in 1940 the Defence Committee decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was ‘neither necessary not desirable’, partly because they believed white Australians would object to serving with them making it much more difficult for our men to enlist.

“When Japan entered the war, however, the increased need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions, and thousands of Indigenous Australians enlisted and served.”

https://www.awm.gov.au/sites/default/files/images/article.jpg

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell is working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served and are currently serving.

“Today, the Australian Defence Force looks to recruits through the Defence Indigenous Development Program, and the actions and involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in all Australian conflicts since prior to Federation is far better known,” Bell said.

“But while many Australians assume that the sorts of discrimination faced by Indigenous servicemen is a thing of the distant past, it doesn’t take much searching to stumble across similar sentiments on social media.

“One of the antidotes to this problem is to learn and tell the many stories of Indigenous service, of those who rose above to fight for the nation that spurned them.

“We’re trying to encourage people to come forward and tell their stories to help us tell the broader story of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience.

“Because no-one saw them, perception of their service was skewed, and for a long time it appeared as if they had never existed.

“It is a little known story that deserves to be widely known.”

After speaking with an MLA and the Housing Commisison, Atkinson and his family were moved to a flat at Herne Bay. Now known as Riverwood, Herne Bay was a housing settlement of timber huts initially built to accommodate casualties during the war. They were converted into Housing Commission flats after the war to help ease the housing shortage. Each hut could house up to three families, and the bathroom was a tin building behind the flat.

Atkinson and his family were eventually moved to a permanent residence in Charles Street, Riverwood, where they lived for almost 30 years.

He remained happily married for the rest of his life, and had the privilege of watching his children and grandchildren grow.

His family said he died on 22 November 1981, having led a life that was more eventful and courageous than most. One thing he never spoke a word about was the war.

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. He is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au

With special thanks to Isabella Walker, Clarence Atkinson's great-granddaughter. Without her research, this article would not have been possible.