'We all owe them'

It was 25 March 1945, and 24-year-old Jack Tredrea was in the back of a Liberator bomber, preparing to parachute ‘blind’ into Japanese-occupied Borneo.

The clouds had rolled in and visibility was poor, but there was no turning back. It was now or never.

Armed with only a few maps, some guns and grenades, and a cyanide pill to swallow in case he was captured, Tredrea thought of his wife back home in South Australia, and then he jumped.

He had tucked the lethal pill into the corner of his mouth for the descent, but spat it out when he exited the clouds to the frightening sight of the dense jungle immediately below and panicked at the sight of the trees rushing towards him.

“Bad luck if the Japs got me,” he later said. “No way was I landing with that in my mouth.”

Jack Tredrea, pictured far right, during the war.

A tailor in civilian life, he was one of a handful of young Allied operatives who parachuted into the remote jungle of Japanese-occupied Borneo in the final months of the Second World War. Their mission was to recruit a guerrilla force of the island’s indigenous Dayak peoples to gather intelligence and fight a secret war against the Japanese. It was to prepare for and support the Australian invasion at Labuan Island and Brunei Bay on Borneo’s north coast, set to take place in June 1945, as part of the Australian-led liberation of the island.

Most had barely encountered Asian or indigenous people before, spoke next to no Borneo languages, and knew little about the Dayaks other than that they had been – and maybe still were – headhunters. They feared the Dayaks might kill them or hand them over to the Japanese.

For their part, some Dayaks have never seen a white face before.

So begins the story of Operation Semut, a secret wartime operation by Special Operations Australia, the shadowy organisation codenamed the Services Reconnaissance Department, but popularly known as Z Special unit.

Jack Tredrea, front right, at Belowit, in May 1945.

“Z was a different operation to anything else,” Tredrea said in an interview in 2018.

“We didn’t know … where we were going until the day we got on the plane.

“I walked every day for five weeks, visiting every kampong – every village – in the highlands of Borneo.

“[We were] gaining all the information we could, and because I was a trained medic as well, I was treating people all the time.

“I did my first operation on the third day.

“The head man of the village said to me, ‘One of our older men can’t walk, would you have a look at him?’ So I went into the kampong and he was lying on a mat alongside a fire.

“He had a golfball-sized lump in his groin, and I thought, ‘Oh, God … that needs to come out.’

“I had no anaesthetic, so I got two of the boys – one to hold his shoulders and arms, the other to hold his feet – and I said, ‘This will hurt a little.’

“The next morning, I was sitting having my breakfast with the others, and he came tottering down the passage, and the first thing he said was, ‘Tuan Doc, Tuan Doc, terima kasih, terima kasih.’ Tuan Doctor. Tuan Doctor. Thank you. Thank you.

“He was a very happy man. And that became my name for the entire time I was in Borneo – Tuan Doc.”

Semut operatives at Labuan in November 1945.

More than 75 years later, the story of Operation Semut is told in an award-winning book, Semut: The untold story of a secret Australian operation in WWII Borneo, by anthropologist Christine Helliwell.

The book won the Australian War Memorial’s 2022 Les Carlyon Literary Prize for military history and has been shortlisted for the 2022 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards to be announced on 13 December. Other shortlistings include the NSW Premier’s History Awards and the prestigious Templer Medal (UK).

“I’m thrilled,” Helliwell said. “Les Carlyon was a monumental figure in Australian writing: not only a great historian, but a wonderful, wonderful wordsmith, so it’s a huge honour to win an award that bears his name.”

The New Zealand-born anthropologist and academic interviewed all of the remaining Semut operatives, as well as more than 120 Dayak people, and consulted thousands of military documents and records from archives around Australia and in Britain to piece together their story.

She captures the sounds, smells and taste of the jungles into which the operatives were plunged, and takes the reader into the lives and longhouses of the Dayaks, on whom their survival depended.

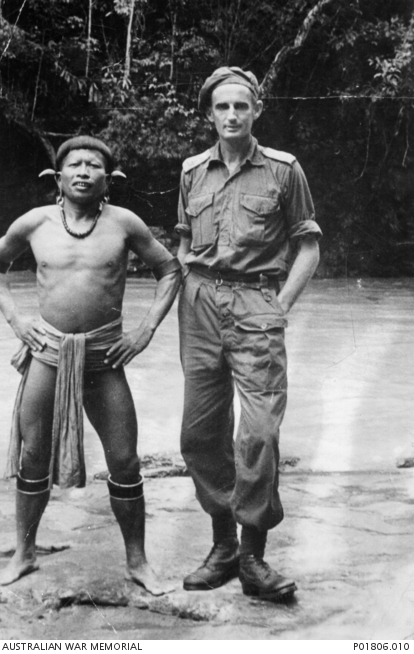

Kelabit chief Dita Bala with Operation Semut leader Major Gordon ‘Toby’ Carter at Long Datih on the Tutoh River, Sarawak, in April 1945. Dita Bala is wearing the teeth of a clouded leopard in his ears and a string of ancient glass beads around his neck, both indicating his high status.

An emeritus professor at the Australian National University, Helliwell has been researching Borneo’s indigenous Dayak peoples for almost 40 years.

She began looking into Z Special unit’s secret wartime operations with the Dayaks as part of a joint-research project with the Australian War Memorial in 2015.

“While I was working on the project, I went to Adelaide to interview a very, very old soldier who had fought in Borneo in 1945,” she said.

“That soldier was Jack Tredrea, and Jack and I just hit it off. He asked me back the next day to have fish and chips with him for lunch, and we just became really good friends.

“He was part of Operation Semut, and it was the first that I’d heard of the operation.

“But that interview really sparked my interest.

A group of Semut operatives at a camp at the top of the Baram River. The operation leader, Toby Carter, is fifth from the left.

A canoe full of Semut guerrillas, flying the Union Jack, advancing down the Baram River to mount an attack against the Japanese.

“There were very few veterans [left], but [there were] lots and lots of families of Operation Semut men who were desperate for the stories to be told.

“Their fathers had not been able to talk for years about the operation because most of them had signed these secrecy declarations ... which forbade them from talking to anybody about it ... but in later years, their fathers, or their uncles, or their grandfathers, had told them little bits and they were desperate to know what it was all about.

“It was also really important for me to tell the story for Jack because Jack desperately wanted the story out there.

“But finally, and in lots and lots of ways, it provided an opportunity to write about the contribution of the local Indigenous people.

“Indigenous people took part to a very significant degree in the war in the Pacific. They helped Allied soldiers. They fought beside Allied soldiers.

“But that contribution had never been properly acknowledged or recognised – certainly with respect to the war in Borneo – so it was really important to me to be able to tell that story for Jack and to write into it the contribution of indigenous Dayaks.

An Iban guerrilla with a rifle slung over his back and a parang in his right hand.

Climbing through Borneo's rugged jungled terrain after the war.

“And so I, unlikeliest of military historians, found myself writing a book about a secret military operation in the heart of Borneo.

“It was a steep, steep learning curve. I knew nothing about military matters when I started this book – absolutely nothing at all.

“I ploughed through thousands of military documents, but I also did a huge number of interviews.

“Talking to these old veterans, who were all by then well into their 90s, was just wonderful.

“It was a great privilege to hear their memories, and to hear them talk.”

She taught herself how to write a page-turner by reading popular military histories at a bookstore in Canberra.

“All my academic instincts were to write some kind of analysis, but I had so much data, I didn’t quite know what kind of analysis to do, so in the end, I decided, I’m just going to tell this as a story for Jack and for the Dayak people who simply wanted this story to be told.”

Anthropologist Christine Helliwell conducting interviews in Borneo. "Interviewing Dayaks for me is always a great privilege," she said.

She wrote the book at her home in Canberra, working 10-hours a day, seven days a week, during one of the Covid-19 lockdowns. Tucked in the corner of her computer screen was a photo of her and Jack.

He had given her carte blanche to write about the operation as it happened, joking: “There’s nothing they can do to me now.”

His only stipulation was that the role of the Dayak peoples should be properly acknowledged.

“You have to tell them how important the Dayaks were,” he told her.

A lump caught in his throat when he remembered the Dayaks, “the finest bunch of people I had the privilege of fighting with.”

The Dayak guerrillas had been the backbone and mainstay of Operation Semut. It could not have succeeded – or even got off the ground – without them. They were armed with rifles and captured Japanese weapons as well as traditional weapons such as the parang, or traditional machete, and blowpipes that fired poisoned darts. Traditional headhunting, which had been outlawed under British colonial rule, was also actively encouraged.

A Lun Bawang man, Basar Paru, who fought with the operatives during the war, told Helliwell: “The white soldiers came. They were good, brave. But we were also brave. I hope that white people’s stories remember us too.”

Christine Helliwell with Jack Tredrea. “I went to Borneo thinking I’d need to teach the Dayaks how to operate and how to fight," he said. "But it turned out that it was mostly them teaching me. Without them, I wouldn’t have lasted a day. They were absolutely marvellous.”

In the final years of his life, Tredrea returned to Borneo every March to commemorate the day the Semut Reconnaissance Party parachuted into the jungle.

When Helliwell asked why he did this, given how gruelling these trips to the centre of Borneo were, he said simply: “They’re wonderful people and I owe them. We all owe them.”

Bob Long, another of the Semut operatives, agreed, telling her: “The Dayaks were our saviours, really.”

Tredrea’s last visit was in March 2017, aged 96. He died in 2018.

“That’s one of the great sadnesses that I have, that Jack never actually lived to see the book and hold it in his hands, because I know it would have brought him immense pleasure,” Helliwell said.

“It was a real labour of love ... both for these veterans, especially Jack, and for the Dayak people.

“It’s really quite wonderful that it’s receiving this kind of recognition because it gives recognition where it’s due – to these remarkable young Allied operatives who parachuted into Japanese-occupied Borneo, but also to the remarkable Dayak people who took them in, fought beside them, and sent them back home again.

“Jack would have been ecstatic.”