'We were all there for each other'

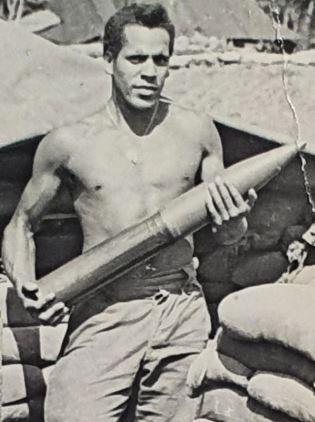

Bombardier John Burns at Nui Dat in 1966. Photo: Courtesy John Burns

John Burns was starting to worry.

It was 18 August 1966, and the battle of Long Tan had broken out. John, a bombardier with the 103 Field Battery at Nui Dat, was providing covering fire for the Australian troops, when his ammunition started to run dangerously low.

”As we were firing, this great downpour hit us,” he said.

“It was one of these monsoon rains. It sounds like a freight train coming at you through the rubber trees, and then all of a sudden it hit. The barrel of the gun was really hot and steam was absolutely pouring off it.

“We were going through our first-line ammunition and I thought, ‘Oh geez, we must be getting close to not having any high explosive shells left.’

“The gun pit was absolutely full of steam and smoke and spent cartridges ... And I thought, ‘How are we going to keep this rate of fire up if I have to take half the detachment away to get more ammunition and carry it back to the gun?’

“That's when I saw all these soldiers running out of the rubber trees. The rain had just cleared and I can still see it as clear as anything in my mind.

“They ran straight to the ammo dump, and they started collecting ammunition shells and carrying them off to the guns.

“That's when I felt so proud. This was the Australian spirit that we all know. We were all Australian diggers, and if a mate’s in trouble we’ll do whatever we can to assist.

“That’s when I realised we were all one. We all wore the same green skin, and we were all there for each other. And that memory is still as vivid in my mind now as it was 56 years ago.

“It was absolutely amazing, and I was never so proud to be a part of it. The Aussie spirit never looked greater than at that moment.”

John Burns, pictured left, with Gunner Bruce Morris during Operation Toan Thang in May 1968.

John, pictured, with Bruce Morris. The pair remain friends to this day. They recreated the picture with the same gun, earlier this year. Photo: Courtesy John Burns and Bruce Morris

A proud Aboriginal elder, John is one of more than 250 Indigenous Australians who served during the Vietnam War.

He is believed to be the only Australian artilleryman who served in two of the most brutal battles Australians fought in during the war – the battle of Long Tan in August 1966 and the battle of Coral-Balmoral in May 1968.

John was born in Brisbane in June 1944, to an Aboriginal mother he never knew. Adopted by an English woman as a baby, he grew up in public housing in Holland Park and never met his biological mother or father.

“She was the only mum I ever knew,” he said.

“It was tough, you’d have to say. If my adoptive mum and I were walking out in public, people would stare at us. Sometimes they would say cruel things. Or maybe just thoughtless things. But in Queensland at that time we knew we were viewed as different ... Less than, in a lot of ways.

"I remember I was getting on a trolley bus. And I can still see this bus driver’s face. He looked straight at me ... and then he said to the conductor, ‘Hey Bill, we’ve got a black snake on the bus. I think he’s frightening the people.’

“Mum used to say to me that those people are so insecure in their own mind that the only way they can feel better is putting somebody else down.

“[But] as an 11-year-old boy, that really hurt.”

John Burns, pictured outside the ammo bay, holding a 105mm shell in 1966. Photo: Courtesy John Burns

John left school at 13 and was working at a Brisbane abattoir when some of his mates suggested he join the Citizen Military Forces.

“They said, ‘Oh, you should join us...’ and the next thing I know I’d been accepted.”

He enlisted in the Regular Army two years later.

“I was talking to one of the corporals, one of the Regular soldiers, and he said, ‘You should join the Regular Army. You’d make a great soldier.’

I didn't really know what I was going do.

“I'd never thought too much about the future except that I just wanted to be able to work.

“I'd learnt a couple of things early on, that maybe jobs weren’t that easy to get because I’d had a few different interviews before I worked at the abattoir.

“I got to the interview stage, but then they said, ‘Oh, no, sorry the position has being filled,’ and you sort of realised why they were telling you that you couldn’t have the job.”

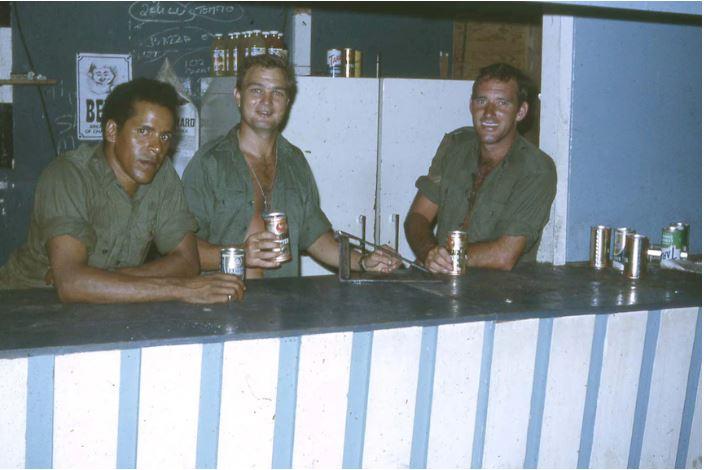

John Burns, left, Larry D'Arcy, centre, and Ian Warren, right, at the Mushroom Club in 1968. Photo: Courtesy John Burns

John was thrilled when he received the letter from the Army saying he had been accepted and was to present himself for enlistment on the 19th of April 1963.

“I was 18,” he said, smiling. “And I've still got the letter to this day.”

He was sent to Vietnam with the 103rd Field Battery in May 1966.

“When we first went over, we thought it was a bit of an adventure,” he said.

“Back in those days, you think you’re bulletproof and Superman. But we had a lot of work to do.

“The Task Force area [at Nui Dat] was just a rubber plantation and we had to develop a gun position.

“We were flown in by Chinooks and we were put in our different gun positions, but you couldn't even see your neighbour next to you. We knew they were only about 40 or 50 metres away at the most, but because it was all bush you couldn’t see a thing.

“We started digging, filling sandbags, and building gun bunds and ammo bays … and then we fired our first round in anger on the 6th of June 1966. And that sort of stayed with me because of all the sixes – it was the sixth of the sixth, sixty six.”

Vietnam, August 1966: Gunners of 103rd Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, heave their 105mm howitzer into position for support fire during Operation Toledo.

Gun pit containing a 105mm L5 pack howitzer of 103 Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, on the south-west perimeter of the base at Nui Dat looking towards a rubber plantation.

He was at Nui Dat when the battle of Long Tan broke out in the nearby rubber plantation two months later.

“We’d got the position going really well, and then on the 17th of August, we got mortared and rocketed,” he said.

“It was the first time the war really touched us, and I must admit it was quite scary.

“The next morning Col Joye and Little Pattie were coming to perform. The sergeant said, ‘You take a couple of the other diggers and go to the show and then I'll go to the second one,’ so away I went.

“That afternoon, I finished work... It must have been about four o'clock. I’d done the maintenance of the gun and wrapped it all up ready for the night.

“I was walking up to the boozer, and as I was walking up there, the 161 Battery – the Kiwi Battery – started firing.

“It was routine for the infantry blokes to register defensive fire targets when they were in the rubber [plantation]...

“So that didn't bother me …

“But then it come over the channel ... Fire Mission Regiment, and I thought, ‘Oh, here we go.’

“I hadn't even had a sip of my beer, and I just left it, and ran back for the gun.

“D Company had been ambushed and they were under attack.

“Things weren’t looking too good because the North Vietnamese Army forces and the Viet Cong numbers surpassed our guys.

“We were firing [in support], and then it came across ‘Danger Close’, so we knew the blokes from 6RAR must have been really close to getting overrun.

“We were just pouring fire out and burning through our first line ammo...

“The noise was unbelievable ... but it wasn’t just us. [It was] the whole regiment ... and all the guns were firing.

“It was absolutely amazing. And apparently we really were ‘Danger Close’, because we did bring that fire down to just about on top of where our guys were.”

Nui Dat, South Vietnam,1966. Two members of 103 Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, firing a 105mm L5 pack Howitzer from a gun pit at 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF).

A 105mm L5 pack howitzer of 103 Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, on the south-west perimeter of the base at Nui Dat, looking sout-west.

Today, the battle of Long Tan is considered one of the fiercest and most intense battles Australians fought in during the Vietnam War.

John would return to Vietnam for a second tour in 1968.

“I came home, but I couldn't settle down,” he said. “I wanted to get back and do a bit more.”

He asked to return, but was told he couldn’t go back to Vietnam for 12 months.

“It wasn't very long after ... the battery commander of 102 Battery said, ‘I hear you want to go back to Vietnam. Would you like to go back with my battery?’

“So I said, ‘I'm in.’

“I’d arrived home from Vietnam on the 3rd of March ’67. And on the 3rd of March ’68, I was on the plane going back.”

It was just after the Tet Offensive. The North Vietnamese had launched a series of coordinated attacks on more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam during the Lunar New Year to stoke rebellion among the South Vietnamese and encourage the United States to scale back its involvement in the war.

“On the road going through Bien Hoa you could see all the damage,” John said.

“They had a theatre where they put shows on… It was the only concrete building in the place and great chunks had been taken out by rockets and 50-cal bullets.

“It must have been terrifying when they came through …

“But I was glad I was back.”

Two months later, John was fighting for his life.

An M2A2 105 mm howitzer of 102 Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, in position at the newly-established Fire Support Base Coral in May 1968.

“We heard a large force was coming south from North Vietnam and they were building up to attack Saigon,” he said.

“We went out on Operation Toan Thang, which meant Final Victory, and I thought, ‘You beauty, we’re going to give it to them, and hopefully this will end the war.’

“Then on the 12th of May… we moved to [set up] Fire Support Base Coral.

“That night we were attacked by ground forces. And again, it was a very scary night.”

The 1RAR mortar platoon position was over-run, along with one of the 102 Field Battery guns – the No. 6 gun. Another was put out of action.

“I remember that night as plain as if it was a night last week,” John said.

“My gun – No. 5 – was ordered to fire splintex, which is an anti-personnel shell or dart.

“You never expect artillery units to be hit by ground forces – you might get mortared and rocketed maybe, but most of the time the artillery units are behind the forward line supporting the infantry battalions out in front, so [for the enemy] to get through to the artillery, something must have gone really wrong.

Fire Support Base Coral, 13 May 1968. Members of 102 Field Battery, 12th Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, with the Battery's No. 6 gun, a 105mm M2A2 howitzer, on the morning after the first series of attacks by troops of the North Vietnamese Army's 7th Division. This position was temporarily overrun by the NVA on the night of 12/13 May 1968 and the 105mm howitzer was seriously damaged.

“On the second night, I think it was, we took a mortar, and it dropped right between the trails of the gun.

“My sleeping pit was a bit away from the gun and I heard the mortars coming down.

“It’s a terrible sound. You can hear the wind whistling through the fins as they are coming down. They make this sort of swishing sound, and you would swear blind it’s right above your head and it’s going to drop right on you.

“You kept saying to yourself, ‘If you can hear them, then they’re not going to hit you.’ But this time, we had one drop right in between the trails of our guns...

“I had my flak jacket and helmet at the top of my sleeping pit, so all I had to do was come up, grab the helmet, put the flak jacket on, and then I was ready to go, but as I stuck my head up, this thing hit.

“I saw this little flash, and I must have known what it was, so I dropped back down.

“The next day, we were sorting everything out and the tarp on our stand-easy area was just shredded with shrapnel.

“Then when I was walking back to my sleeping pit later on that day, I looked at it, and right in the middle of this sandbag, right where my head would have been, there was a big hole where a piece of shrapnel had gone straight into it.

“If it had been an inch or so higher, it would have cleared the sandbag and it would have taken the top of my head off.

“But I was lucky. I wasn’t meant to go then. I was meant to come home and marry the love of my life, who was patiently waiting for me.”

John Burns, right, with Larry D'Arcy, left, and Robert Costello, centre, on May 13, 1968, the morning after the battle of Coral.

John returned to Australia on 5 February – his mother’s birthday – and married his fiancée, Valmai, ten days later. They had written to each other every week while he was away.

Coming home though, he faced a battle of a different kind.

“It wasn’t just me,” he said. “All the guys that came home from Vietnam ... we were vilified.

“We were called murderers, baby killers. Some had red paint thrown at them.

“I always get a bit angry [about it], and just telling it again, I felt angry.

“We were there to help the South Vietnamese people who didn’t want to be under Communist oppression.

“Our government told us that’s what we would be doing – that we’d be helping the South Vietnamese people live in peace and harmony. I really believed that, and that’s why I wanted to be part of it.

“I would have gone back again, only my wife wouldn’t let me … she said, “No ... no going back to Vietnam a third time, you’ve risked your life twice, don’t do it again.’”

Uncle John Burns. Photo: Courtesy Belinda Mason/Serving Country

John went on to serve in the Army for 23 years, retiring as a Warrant Officer Class 2 in July 1986.

Like other Indigenous Australians who served, he does not regard his service as different from that of anyone else.

“I know all of the Indigenous servicemen feel the same,” he said. “You don’t really want to be singled out. We all wore the green skin – we were all there to do a job, to defend our country – but I think it’s a great thing that people know the history and that we’re always there to help defend our country.

“Doing things like this, it brings us a millimetre closer to reconciliation...

“I always said I was really proud to be part of that battle of Long Tan on the guns, and I was probably just thankful that we got through Coral.

“I feel really blessed.”

John Burns is one of more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers who served during the Vietnam War and are now listed on the Australian War Memorial’s Indigenous Service List. The Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell has been working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is interested in further details of the military history of all those people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au