Australia’s Boer War

Craig Wilcox’s Australia’s Boer War: the war in South Africa, 1899–1902, Oxford, 2002 (published in association with the Australian War Memorial) appeared recently. In the first of two adapted extracts from the book, Wilcox describes a typical day experienced by Australian soldiers in South Africa; in the second extract, he reminds us of a war crime by an Australian that went unpunished.

On the veld

The young man stands, stretches, and shivers a little in the cold, violet dawn. He looks nothing like the well-dressed actors in Bruce Beresford’s film Breaker Morant. His face is heavily bearded. He has a thin brown blanket or khaki greatcoat around his shoulders, and his legs, hands, and face feel cold. He scratches at the lice that have tormented him for months. His cord breeches are rags, and the cloth puttees that once wound so neatly around his lower legs are disintegrating into shreds. The dented cork helmet or shapeless felt hat that keeps the sun off his nose and ears at midday cannot warm his head at night, and at the moment he is wearing a stocking cap or balaclava.

If he has some tobacco he crams it into his pipe and smokes it—unless it’s too awful to stomach so early in the morning, or the little flame has been deemed likely to present a target to a sniper.

Tobacco may be all the breakfast he has, unless he and his comrades have the services of a cook or an African servant—and many Australians soldiers in South Africa did. He might be in line for some lukewarm tea in a filthy enamel mug, maybe a few mouthfuls of porridge concocted from sugar, water and broken army biscuits called “fortyniners” for their many perforations.

Above the wiggle of low purple hills that form the horizon the sky is already a fantastic orange, heralding another hot day on the veld – the vast South African plateau where most of the Boer war of 1899–1902 was fought.

Not quite as bedraggled as the man described in this article, these soldiers nevertheless look weary and dishevelled as they face another day on the veld. C42309

A typical day for Australian soldiers in the war saw them march several kilometres or more, trying to locate their elusive enemy. If successful, or if the enemy found them, then a skirmish would ensue that sometimes resembled a shootout in a screen western, with much hard riding and a few brief, shocking bursts of gunfire at close range.

More controversially, the typical day would also include some form of looting and destruction.

Officially forbidden, looting was almost universal. “Everyone loots, of course,” explained Captain Harry Chauvel, who maintained that his Queensland unit looted “ in a gentlemanly manner and as a rule rob neither women nor the honest kaffir”, this being a common name for Africans. Looting was often prompted by a hunger made inevitable by the army’s inability or unwillingness to feed its soldiers adequately – and “an empty stomach has no conscience”, as Corporal Jack Abbott of the 1st Australian Horse put it. One Tasmanian wrote, “even the most honest man in civil life will become the biggest thief on active service”.

But looting for food shaded easily into looting for gain. Even Boer bibles were not safe, being prized as souvenirs. Some Australians were drawn to “cattle fraud”, as impounding Boer cattle and selling them for profit was called. William Thomas, a Queenslander, was sent to jail in England for two years for the crime. No Australian back home protested against the sentence. Looting could impoverish whole districts, but destruction could make them uninhabitable for months or years. Typical forms of destruction were the burning of Boer farms and the slaughtering of their animals (whole brigades of soldiers sometimes paused for a day to cut the throats of local sheep) and the dynamiting of entire rural towns. Some farms were incinerated accidentally or simply to produce a few smoking shards of timber to light soldiers’ fires, but generally destruction was official policy.

A few soldiers were sickened by it. “I hate the whole business,” wrote Major Hubert Murray from Sydney. But even those who hated it usually thought it was just, or at least justifiable. “It seems a cruel thing to ride up to a farmhouse and give the inmates, always women and children, ten minutes to clear out what personal effects they can get together and then to set fire to the place,” wrote another officer from Sydney, “but when their husbands and brothers are up on the hills behind sniping at us, what else can you expect?” In any case, most soldiers enjoyed looting and burning. “The best part of this game is sacking the houses,” confessed Lieutenant Douglas Rich from Queensland, “ although we poor devils of officers don’t get much of the fun as in most cases it is forbidden and we have to keep the men back.”

A burning Boer farmhouse, one of many destroyed during the war. Some Australians found this aspect of the war distasteful; many others enjoyed it. C38307

At the end of the day, if the marching and fighting is over, it is time to camp inside a comforting ring of outposts whose guards change every couple of hours. Mules are tied together by their African drivers and led to a creek or dam, where the soldiers’ horses are already drinking before they will be picketed for the night. If there are farms nearby there might be pieces of furniture for fuel, chickens and pigs for food, and fodder for the horses. Soldiers move about with their coats unbuttoned and puttees removed, a motley, shabby, lousy, happy crowd. There will be banter and mockery, perhaps a singalong or recitation later. A few soldiers slip away for “a bit of fun” with some local African women.

“ It is a queer life this,” Jack Abbott explained. “No one at home can know it exactly as it is. No one out here can quite describe it. It is rough, it is hard and it is dangerous, but it is intensely interesting and exciting. The glorious healthiness of it is its perfect charm. There are fever, and dysentery, and pneumonia—but, provided that you can keep clear of these, you will almost fatten on it.”

It killed a thousand Australian soldiers all the same.

The killing of Jan Dolley

Captain Charles Cox’s squadron of New South Wales Lancers was the first group of Australian soldiers to land in South Africa to help the British army fight the Boer War of 1899–1902. When they landed in Cape Town early in November 1899, Cox boasted that his soldiers were trained cavalrymen and born bushmen. The boast was a wild one, but it went over well with the crowd who heard it. They would be less impressed when they heard of Cox’s first contribution to the imperial war effort.

Cox and some of the lancers were sent inland to join the army’s defence of Colesberg, a rural district under attack from Boer commandos. Local white farmers favoured the Boers, and would support them given the chance or if provoked by the army. They were already angry at the imposition of martial law. The army needed to show firmness on the battlefield and discretion off it. Cox’s lancers showed neither.

On 22 November Cox led a small patrol to a farm to arrest some young men who were itching to join the Boers, and also to impound their horses. The arrests went smoothly enough. Then one of the family’s African servants, Jan (the equivalent of “John”) Dolley, refused to help look for a bridle that the patrol needed if all the horses were to be taken away. “If he won’t give you the bridle, give him a hole,” Cox told a policeman riding with the patrol. A few seconds later a shot rang out.

Dolley’s wife, Louisa, was also a servant at the farm. She heard the shot from inside the farmhouse, but didn’t know its awful consequence until the farmer’s little girl up ran to her screaming that her husband had been killed. She hurried outside and found that Cox’s order had been obeyed to the letter. Jan Dolley was lying dead in a stable, a hole through his head.

“ I saw the first shot fired yesterday,” Cox wrote home in a letter after the patrol returned to its base. He didn’t bother to mention that it was a civilian who died from it. Being ignorant of South Africa’s complex social relations and of the brittle relationship between the parliament in Cape Town and the British army, he didn’t expect the killing of a black man to have any significance. But it produced a scandal that dogged Cox and the British army for a year.

Jan Dolley had been a trusted family servant, well known and much loved in his district. His shooting was seen as a coldblooded murder by white farmers, especially those with little love for the British army. They protested to the army and to the government in Cape Town. Dolley’s killing, along with other incidents, led the Cape parliament to create a special court to punish crimes committed under martial law, whether by civilians resisting it or by soldiers enforcing it. A trial for Jan Dolley’s murder was listed as the court’s first case. The penalty for murder was death.

Britain’s high commissioner in South Africa, Sir Alfred Milner, was worried, as was the army. A chink had appeared in the imperial armour which hostile civilians could exploit. And a valued custom was under threat—the custom that Australian soldiers, like other volunteers with the army in South Africa, were generally indulged by the authorities, excused most discipline, protected from harsh punishment. Milner suggested that Cox be shipped back to Australia, beyond the court’s reach. Instead the army struck a deal with the Cape government. Soldiers and police operating inside a district under martial law, as Colesberg had been, might appear in court, but not normally come under its jurisdiction.

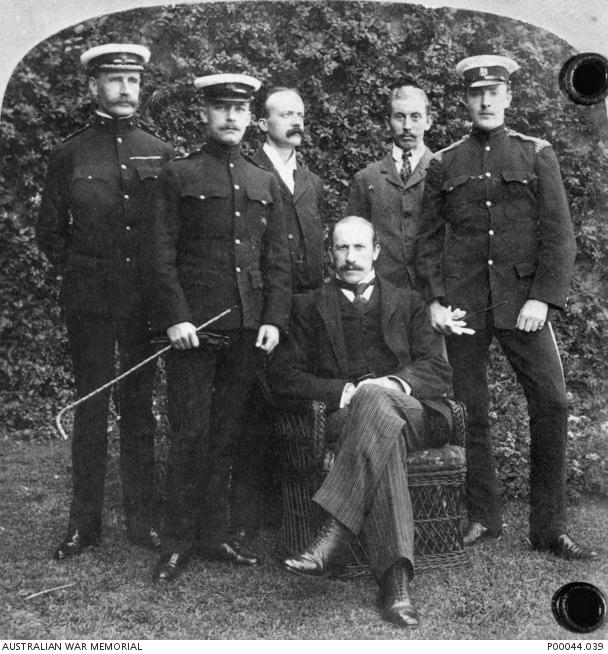

Sir Alfred Milner (seated), Britain’s High Commissioner to South Africa. Milner was worried about the repercussions of Dolley’s killing. C40125

Cox went into the dock in Cape Town in October 1900. He admitted giving the order that killed Jan Dolley. The policeman admitted firing the shot. But under the terms of the deal both men walked from the courtroom scot free. The deal which saved Charles Cox from the fate of Harry “ Breaker” Morant 16 months later offended even the staunchest South African supporter of the empire and its army. “The whole affair stinks in our nostrils,” fumed a Colesberg newspaper.

But when the trial was reported in Australia, not a word of protest was heard.

Charles Cox had been officially exonerated, after all. But there were other reasons why Australians were silent. The death of an unknown black foreigner was unlikely to stir much interest. And Australians expected the British army to play the role of benign host to their soldiers, paying them high wages, excusing them from most discipline, protecting them from the consequences of their actions.

No wonder the killing of Breaker Morant, when the army ceased for a moment to play benign host, caused such a shock.