Stella Bowen: Article

Art, Love and War

Consider what o'clock it is,consider what a long way you've come today. Consider what a great girl you are, only don't cry.1

The expatriate Australian artist Stella Bowen was a woman of enormous integrity and generosity. After Bowens death on 30 October 1947, her friend Keith Hancock wrote to her daughter, Julia Loewe: Stella was the most courageous, vital and harmonious personality that I have known ... Her death is a waste, for she had so much to live for and such a genius for living.2 But it is for her art that she is remembered today, in particular, the war drawings and paintings she created towards the end of her life.

Having left a comfortable Adelaide middle-class upbringing in 1914 to find artistic training in Europe, Bowen spent the next thirty-three years seeking her own visual form of expression. This quest led her from England to France, America and eventually back to England. It took her from a provincial Australian city into the literary milieu of England and France, which expanded her horizons beyond anything she could have imagined. It also allowed her to break all the social conventions previously imposed on her by falling in love with a married man nineteen years her senior and having his daughter. Despite all the difficulties and hardships she endured, Bowen remained true to herself and to her passion for art and life.

Since the Second World War, the largest collection of Bowens work has been housed at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, the legacy of her time as an official war artist. It was just prior to her fiftieth birthday that the Australian High Commission in London, on behalf of the Australian War Memorial, approached Bowen with the offer of an appointment.

After painting two portraits for the Memorial, Bowen was assigned to the RAF station at Binbrook in Lincolnshire in the north-east of England. This allowed her to pursue her interest in group portraiture. She was asked to paint a typical Lancaster bomber crew, and it proved to be an emotionally difficult subject.

The resulting work, Bomber crew 1944, is one of the best known of Bowens paintings and draws together many of her artistic preoccupations: the use of a formal composition, diffuse light, decorative elements and thin paint surfaces. Bowen completed the portrait in her London studio after the crew failed to return from a bombing operation over Germany, using the sketches she made at Binbrook and official photographs of the crew. Bowen painted seven overlapping,disembodied figures with angelic faces; they have glazed eyes, and there is no engagement with the viewer. She depicted the black Lancaster bomber as hovering like a bird of prey, or perhaps even a vulture, over their heads. In the lower part of the picture, a wreath-like ribbon scrolls across the surface and the airmens flying wings float like tiny angels. Bowen wrote to her brother about the work: It was horrible having to finish the picture after the men were lost. Like painting ghosts.3

Bomber crew is an iconic work, the culmination of a lifelong struggle to establish her own style, years in which she experimented with different painting techniques and built up a visual vocabulary of approaches. Taken together, the paintings of the war years are the final expression of a mature and remarkable painter, who displayed in them the compositional, stylistic and technical skills she had been exploring in her art.

The five essays in this catalogue focus on different aspects of the life and work of Stella Bowen. This introductory essay will supply a context for her work through an overview of her life and artistic development. The remaining pieces treat various aspects of Bowens life and art: Jane Hylton recalls her ongoing relationship with Adelaide and the family and friends she left behind; Joseph Wiesenfarth examines her life with the English novelist Ford Madox Ford; Laura Back discusses her preoccupation with establishing a home, in both the physical and emotional senses; and, finally, Fiona Clarke recounts her experience as an official war artist.

Art

I suppose this gift of creating life at a touch is the most enviable gift that a painter can have.4

Stella Bowens passion for art developed from an early age, despite the strictures of a conservative upbringing in Adelaide, South Australia. Born on 16 May 1893, just before the turn of the century, she convinced her mother to allow her to take art classes in her early teens and, indeed, to decorate her room by painting the walls. However, it was only when she began to study with Rose MacPherson (Margaret Preston) around 1910 that her imagination was fired: she began to seek to free her artistic expression and challenge the limitations of her life.

There are few surviving works from this period to provide evidence of Bowens youthful passion: a watercolour of boats, a small painting of an oriental blue kettle, with roses and a vase, and three charcoal drawings of old men. The drawings relate to some portrait studies she undertook in an old peoples home; she drew them delicately, emphasising light and shade and the detail of their features. Both domestic interiors and portraits were to remain key subjects throughout Bowens artistic life.

When her mother died in 1914, Bowen left Adelaide for England. Her mother had strongly discouraged Bowen from pursuing an artistic career, but her death freed Bowen to pursue her dreams. With an allowance of £20 per month, she embarked on the grand adventure to become an artist and to explore the world. In so doing, she challenged all the middle-class values that had been an essential part of her upbringing.

Initially, she felt lonely in London but soon developed friendships with other young women from similarly restrictive backgrounds who were also trying to come to terms with the greater social freedoms available to young women at that time. She began what were to prove lifelong friendships with Phyllis Reid, Mary Butts and Margaret Postgate. At first she moved from one conservative boarding house to another and must have felt she had hardly escaped the restrictive upbringing she thought she had left behind. But this changed when she moved to Chelsea to board with a young married couple, and they introduced her to models in trousers, page-boy hair bobs, mascare d [sic ] eyes, unmanly youths and unfeminine girls.5 Her life was not particularly affected by the First World War, although she did admit to finding herself to be a natural pacifist .6 She worked briefly as a volunteer with Mary Butts on the Childrens Care Committee in Hackney Wick in 1915. A number of her friends were conscientious objectors, and one in particular, Margaret Postgates brother, Raymond, was imprisoned for objecting.

Raymond Postgate painted in London, 1922 oil on canvas 32.6 x 25.6 cm private collection

Bowens original intention had been to return home to care for her brother Tom, but when he wrote to say that she need not do so as he was enlisting as a soldier, she cashed in her return ticket and enrolled as a full-time art student. The school was one that had been recommended by artists in Adelaide, but she soon came to regard it as boring and conservative and not worth attending. After Bowen had completed innumerable large and heavily-modelled nudes in charcoal,7 she moved to the Westminster School, where the artist Walter Sickert was one of the teachers. He taught her to be more spontaneous in her art and to develop an individual style.

Despite the war, life in England provided many social opportunities for a young woman. Bowen and her friends went to parties, the Proms, walked in Kew Gardens, and socialised at cafés, clubs and restaurants. Then Stella Bowens life changed dramatically after a chance meeting with the American poet Ezra Pound. Pound took the young colonial girl under his wing and introduced her into Londons literary and artistic circles. He organised weekly dinners at Bellottis in Soho, attended by T.S.Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, William Butler Yeats, May Sinclair, and many others. It was at one of these dinners that Pound introduced her to Violet Hunt, a meeting that was to have a profound, though unexpected, effect on her future life.

Art And Love

Why are people allowed and women encouraged to stake their lives, careers, economic position, and hopes of happiness on love?8

It was at Violet Hunts cottage in Sussex in 1917 that Bowen met the one and only love of her life, the novelist Ford Madox Ford, a man almost twenty years older than she. They began writing to each other in October 1917, while he was stationed at Redcar in Yorkshire9 and she was sharing Pembroke Studios with Phyllis Reid. For over twelve months, Bowen and Ford corresponded, trying to conceal their liaison from Hunt, who had been Fords previous lover.

In 1919 Ford moved to Red Ford Cottage in Sussex in search of a quiet place to write and to recover from shell shock after serving at the front. Bowen joined him there a few months later. Very much in love, she allowed her art to take second place while she adapted to rural life in the picturesque but primitive cottage, attending to Ford and entertaining his friends. She immersed herself in this new experience, almost oblivious to the spartan living conditions. However, she did find some time for her own work, painting a portrait of Ford for Violet Hunt and a self-portrait to be given to her brother Tom.

In 1919, Ford changed his name by deed poll from Ford Madox Hueffer to Ford Madox Ford. His wife, Elsie Martindale, still refused to divorce him, and at times Hunt also called herself Mrs Hueffer. In a letter to Herbert Read, Ford referred to his new partner: My Establishment ... includes a Mrs Ford whom you dont know but who, besides ministering to my, really, declining years, paints portraits of-generally-ugly people.10 In the late summer of 1920, Ford and Bowen moved to Coopers Cottage in Sussex (purchased partly from the sale of film rights for his novel Romance ). Later that year, on 29 November 1920, Bowen gave birth to their daughter, Esther Julia Ford.11 Inevitably, she found that art became not much more than a pastime, as motherhood and being consort to another and more important muse took precedence.12

Few paintings have been located from this period that can give an indication of Bowens style and technique. The earliest identified portrait of Ford, Ford Madox Ford c.1920, is small and has been painted over another portrait. Bowen painted Fords face with small detailed brush strokes, and the green shawl round his shoulders in a more vigorous style. She was experimenting with looser brush strokes and a more spontaneous approach to the application of paint, following her association with Walter Sickert.13 She also used this lively, painterly approach in a small portrait of her friend Raymond Postgate in 1922. The youthful Postgate is sitting casually in his crumpled suit smoking a pipe in front of a back-drop of newspapers. Bowen used a colourful handling in depicting the features and unconstrained brush strokes a more individualistic approach to her subjects than the laboured tonal qualities she had adopted during her Adelaide years.

By the end of 1922, the couple had lost their enthusiasm for living in quaint but primitive cottages. In his autobiography, It was the nightingale, Ford wrote: I dont think I could have lived, with damaged lungs, through a third winter. It had seemed to rise up before me like a black wall that I could never cross.14 Their friend Harold Munro unexpectedly offered them his scenic, though relatively inaccessible, peasant s cottage at Villefranche, Cap Ferrat, in the south of France.

After the damp greyness of life in England, Bowen revelled in this part of France, even though their domestic facilities were just as basic as they had been in Britain. Fords letters provide lively descriptions of their experiences in Munros cottage:

This is a comic place: we have the Duke of Connaught on one side of us, & the Rothschilds next door & the Louis Mountbattens with all the wealth of Cassell just above us & all the divorcing duchesses, Westminsters & Marlboroughs in rows along the waters edge below; & white marble & palm trees & Ricket s [sic ] blue sea & Monte Carlo & its vices & splendours ten minutes away ... Stella is painting pictures for all the world like the posters of the P(aris)-L(yons)-M(editerranean Railway) and I cant write at all.15

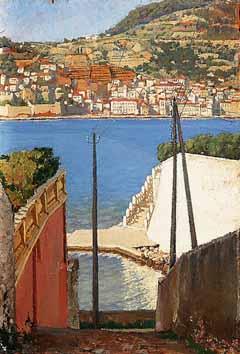

Bowen painted Villefranche 1923 in this cottage. She painted it thinly on a wood panel, capturing the Rickets [sic ] blue sea in the bay, the dazzling white wall and sun-filled landscape.

Villefranche painted in Cap Ferrat, France, 1923 oil on wood panel 34.6 x 26.7 cm private collection

It was the trip she took to Italy in March 1923, at the invitation of Dorothy and Ezra Pound, that was to have the most profound effect on Bowen. Briefly freed of domestic responsibility (Ford and Julia stayed behind), she visited Florence, Perugia, Assisi, Cortona, Arezzo and Siena over a period of three weeks. Here she discovered the formal composition and thin paint16 of the early Italian masters Giotto, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca and Simone Martini. She was delighted by the landscape and architecture and during the trip did some small watercolour sketches, including Assisi 1923 and Cortona 1923. She later wrote:

I had expected something soft and romantic, and behold! I had seen a hard country where everything had a lovely edge to it, and fell into marvellous formal patterns. Trees in serried rows and rocks in sequence and rivers in the exact position required to compose the picture. Old towns crowning symmetrical hills, with ramparts like a collar round the neck; bridges and towers and churches, their yellow-grey stone almost indistinguishable from the rocks upon which they stood, until a second glance revealed their keen, austere, and unblurred edges.17

Ezra Pound, a modernist writer who expected his fellow artists to adopt a similar approach, was critical of Bowens attempts after this trip to copy the Italian painters. But Ford understood what she was attempting:

As for not going to the Old Fellows you must go to them! to the serene ones, like Holbein & Cranach & Simone Martini ... Darling: I assure you that you have all the makings of an artist; the only thing you need being a certain self-confidence. If you attained to that you would see that, even in your work as it is, there is the quality of serenity of imperturbability.18

On her return to Cap Ferrat, Bowen completed a number of small portraits, including one of Ford (Ford Madox Ford 1923). This was her first, unsuccessful attempt to flatten shapes and concentrate on linear design. Although using the ideas of the early Italian primitives, she was also adopting the formalist ideas of Roger Fry and the English post-impressionists. She presented Ford formally attired in a suit, with a ruddy complexion and drooping lip, the latter disfigurement the result of an explosion that threw him to the ground during the war. It was one of three portraits that Bowen exhibited at the Salon dAutomne in 1923. The following year, Ford took the portrait to London and presented it to his mother, who exclaimed that it made him look like a Frenchman with a past .19

Bowen lived in France during one of the twentieth centurys most bohemian decades. With the return of the soldiers from the war, social change was inevitable. High exchange rates on foreign currency encouraged an influx of foreigners; the censorship that had been imposed ended; and it was a time that tolerated considerable sexual freedom. Writers, artists and musicians thrived in the booming Parisian café society and there was an explosion of creative possibilities. Wealthy American women such as Gertrude Stein, Natalie Barney and Winnaretta Singer presided over salons where the artists, musicians and writers gathered. Writers such as Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, F.Scott Fitzgerald and Ezra Pound gathered at Sylvia Beachs English-language bookshop, Shakespeare and Company . Cubism, Dadaism and Surrealism flourished and declined; society seethed with idealism and excess.

The family had moved to Paris after their summer at Cap Ferrat and Bowen revelled in the artistic and social life of the capital. But she pursued her own direction in her art, seeking to create a vision that remained intimate and personal. She portrayed her friendships, and in particular her preoccupation with creating domestic harmony for herself, Ford and Julia, in the ever-changing apartments in which they were forced to live.

Ford and Bowen were never able to purchase a permanent residence after they left England. When they sold Coopers Cottage, they put the money into a magazine that Ford was editing, the Transatlantic Review. Ford, ever the writer and always keen to support new writers, had wanted to establish a literary magazine and he financed this with money from Bowens inheritance and from a major sponsor in America. Ford gave all his energy and financial resources to the magazine for the twelve months of its existence. During this anxious period, he was briefly distracted by an affair with the poverty- stricken and emotionally distraught young writer Jean Rhys, the first in a series of muses that would create a rift between Bowen and Ford. Despite the relationship having ended, Ford and Bowen provided financial support for Rhys until 1927. Bowen remained by Fords side through the financial difficulties and the death of the magazine, yet she realised that the relationship with Rhys had cut the fundamental tie between himself and me, and it showed me a side of life of which I had no previous knowledge.20

By 1925, Bowen had established a studio of her own at 84 rue Notre Dame des Champs where she had light and space, as well as the freedom to paint for as long as she wished. She did not need to look after her daughter as Julia was now living in the country near Paris with her nanny, Madame Annie. Ford and Bowen visited her every weekend. That summer Bowen exhibited a portrait of Madame Serruys at the Société National des Beaux Arts.21

During the mid-1920s, Ford, Bowen, Julie and the nanny spent considerable time in the south of France, always in cheap, rather primitive accommodation. A visit to Toulon in the winter of 1924 25 gave Bowen the opportunity to paint more outdoor subjects. Juan Gris found them rooms in a hotel there, and Othon Friesz found Bowen a studio. For the first time, Bowen was surrounded by artists rather than writers; Henri Matisse dined with them on one occasion. Bowen fell completely in love with Toulon and painted it using the formal and linear design approach she had adopted:

Seen from the harbour, Toulon consisted of a long row of tall, shabby and colourful old houses, unmarred by any intrusion of modernity. This unshuttered and balconied façade, topped by bunches of crooked chimneys, reared itself like a cardboard cut-out in front of a drop-cloth representing an impressive circle of rocky, fortress-capped mountains.22

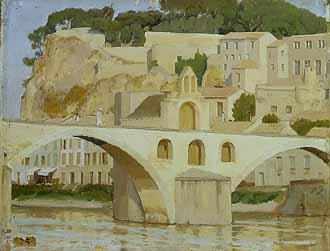

In another work, Bridge at Avignon 1926, she made use of her earlier Italian experience, particularly in the use of a light palette. She created spatial geometry through the curves of the bridge and repetition of the rectangular windows in the façades and in this way constructed a harmonious composition.

Bridge at Avignon painted in Avignon, France, 1926 oil on wood panel 27 x 35 cm private collection

As her relationship with Ford became more strained, Bowen replaced the colours of her early sun-drenched paintings with more muted ones that reflected the sadness she felt. However, with Fords departure for America at the end of 1926, Bowen discovered the emotional freedom to paint whenever she wanted and, in particular, the opportunity to complete a more ambitious painting project, Le Restaurant Lavigne [Au Nègre de Toulouse ] 1927.23 This was a triptych of the proprietors, Monsieur and Madame Lavigne, and staff of Le Nègre de Toulouse, the restaurant they had frequented in Montparnasse. Her process in constructing this painting was elaborate: first, she made drawings (her dollies, as she called them) of the restaurant personnel, then she developed the composition by pasting the images on boards: This was a perfectly formal pattern done on a gold background with M. and Mme Lavigne in the middle surrounded by appropriate decorations and the waitresses grouped at the sides like a chorus of angels.24 While enthusiastic about the work, nevertheless she experienced a growing loneliness without Ford, and fell into artistic despair as she grappled with the formal composition of overlapping figures. She was inspired by the triptychs she had seen in the Italian churches, museums and galleries, but she was re-working these old ideas into a new art, and doing so alone, without the advice and support of other artists, or the encouragement of her mentor.

Bowen was consistently interested in line drawing, as is evident in these preparatory drawings and in the other linear portraits she completed. In the coloured pastel, crayon and pencil drawings Ford Madox Ford c.1925, Sisley Huddleston c.1925, and Julia Madox Ford 1927, Bowen achieved a remarkable clarity of line. She had an ability for capturing a likeness. Many years earlier Ford had published a book on the English artist Hans Holbein and had imparted his interest to Bowen. Following in this tradition, Bowen presented her subjects as solemn and tranquil, rarely engaging directly with the viewer.

With Ford away in New York, Bowen entered one of the most productive periods in her artistic career. She sent him photographs of her two most recent works, Ford playing solitaire 1927 and Le Restaurant Lavigne 1927. She was pleased with both paintings as they highlighted her success in synthesising her Italian experience. The one of Ford is without doubt her most successful portrait of him. She created a religious serenity through the simplicity of the background, the stillness of the pose and the limited palette. In the judgement of journalist Sisley Huddleston, Bowen was

a promising painter who has made an excellent likeness of him. It represents him playing a game of patience with his mouth half open like a fly-trap, as we used to say ... In the portrait the flaxen hair, the pale blue eyes, the open mouth suggest passivity that is, if one believes in any form of inspiration, receptivity. Ford writes only after he has, as it were, hypnotised himself in this manner.25

Ford also praised these works:

They came out admirably, I think I particularly like the Lavigne & myself: they have the austerity & strength of real masterpieces. I do congratulate you & feel ever so proud of you. And you yourself must be pleased & proud: I dont suppose that, by now, you have any doubts of yr. mission!26

During 1927 Bowen painted Reclining nude, experimenting with creating luminosity by layering her paint. She segmented the canvas into four main areas: the decorative red curtain, the reclining nude, black hair framing the head, and the luxurious quilt. Her use of the decorative interplay of sensual, languid and elongated curves is reminiscent of Henri Matisse and Amedeo Modigliani.

Reclining nude painted in Paris, 1927 oil on wood panel 32.6 x 41 cm private collection

Also around this time, Bowen painted her daughter (Julia c.1928); she is portrayed as a child in a conventional manner, but with love and a high degree of technical skill. Bowen showed Julia sitting quietly on a stool, gazing towards the light source that illuminates her face, arms and legs. In her portrait Mary Widney c.1927, she created a Madonna image, the eyes turned away from the viewer and the face with its porcelain features framed by a luxurious fur collar. She captured the brown tones and serene pose in the reflection of the subject in a mirror behind the sitter. In keeping with her interest in El Greco, she sought to paint receding space.27

Gertrude Stein and the Russian artist Pavel Tchelitcheff introduced Bowen to Edith Sitwell and while she painted Sitwells portrait she developed a firm friendship with the writer. She painted Sitwell sitting in her studio on an old inlaid chest that doubled as a coal-box, with the subjects image reflected in a mirror. The smooth and flat painting technique that Bowen had developed after her Italian journey has given way to a layering technique that she referred to as architectural layering. It gave her greater scope to create texture. By now, Bowen was using the muted shades of green and brown, colours also used by Sickert. She admitted that she loved painting hands and enjoyed Sitwells elongated fingers adorned with large rings. In Le masque c.1930, she painted Sitwells extravagant hands with their huge Victorian ornaments holding an African mask.28 In this small, sensual painting, the dark mask and large bracelet on Sitwells arm stand in contrast to the hands and the muted pink tones of the background.

At the end of the nine-year liaison with Ford, Bowen painted her Self-portrait c.1928. A shadowy mask covers her face but the eyes engage the viewer. Despite the sadness and solemnity of the portrait, there is a decorative quality in the interplay of curves and colour. The colours are bold: red, black and white. As in all her paintings at this time, drawing underpins the composition. Bowens outpouring of her grief and loneliness is evident in Fords chair c.1928. Very thinly painted on canvas, the empty chair, the leafless trees, the overcast sky and the brown palette accentuate the bleakness of the scene.

After the crash of the Wall Street Stock Exchange in 1929, many of the Americans who had enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle in Paris suddenly found themselves forced to return home. Many commercial galleries closed and there was a decline in portrait commissions for artists like Bowen. By 1931, as she struggled to maintain herself and Julia on her ever diminishing income, Bowen embarked on a furious bout of painting in order to mount an exhibition of her work in Paris.29 She also included some of the paintings completed in 1928 when she holidayed in the mountains at Argentière, Haute- Savoie. Her fascination with the terrain, particularly the glacier forcing its way down the mountain, led to Le glacier 1928 and Bouche de glacier 1928. (She exchanged the latter for a spring coat.) Fraught with anxiety about the exhibition, Bowen was immensely relieved when she received positive comments from her friends and sold a third of her pictures.

Ford was now living with the artist Janice Biala in a villa at Cap Brun, near Toulon; he persuaded Bowen to take Julia there during the winter (while Ford and Biala returned to Paris) rather than to her old attic studio at Toulon. La terrasse c.1931 was painted in this villa:

I used to sleep in the alcove, looking across the polished tiles of the floor, over the sill of the open door, over the balustrade and the tops of the distant trees, across the dim blue water and into the vast starry sky.30

Very loosely painted in tones of brown and grey, the overall effect is very bleak. It was October and the weather had changed but Bowen also felt empty and uninspired herself. The broken tree that she gazes upon is a metaphor for her mood at the time. Only the French doors and part of the bedclothes and bed indicate that the view is from her bedroom.

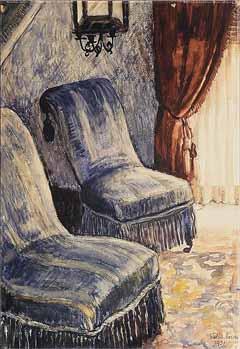

With her remaining savings, Bowen converted her apartment at 18 rue Boissonnade in Paris into two, so that she could rent one out and live in the other. Her resources were stretched to capacity, and her friends Hadley Hemingway and Edith Sitwell offered to help with the quarterly payments to the architect. She painted Interior, Paris 1931 a more joyful work in watercolour with a lighter palette, capturing the intimacy of the room with the two chairs positioned by the window.

Interior, Paris painted in Paris, 1931 watercolour over pencil on cardboard 55 x 38 cm private collection

A second (and newly-discovered) self-portrait, painted in Paris, dates from this period. It reveals a mature woman: her hair is loose, the face thinner, older and wiser. Once again, Bowen partially shrouds her features in shadow and yet the eyes still directly engage with the viewer. She employs her architectural layering of paint, using earthy tones, but it lacks the bold colours and interplay of curves evident in the earlier self-portrait.

By 1932, with the effects of the Great Depression biting hard into her commissions, Bowen was encouraged by friends to travel to the east coast of America to paint portraits for wealthy Americans. She travelled to New York and then to New England and Vermont, often finding herself in the homes of strangers. She missed Julia, who stayed in Paris with Ford and Biala. Yet she took pleasure in some of the unaccustomed comforts:

People have liked my pictures a lot, & if it were not for the depression I can see how certainly I'd have got many more orders ... Most painters are just starving, & Ive only had work because Ive been painting children, & doing them for 1/2 price ... This sort of work involves staying in the most absurdly luxurious country homes, with the most alien kind of people, the whole matter having little enough to do with the Art of Painting! It is just that I can make a likeness.31

In June she visited her friends Ramon and Marguerite Guthrie at Norwich in Vermont.Guthrie, a Professor of French at Dartmouth College, had organised some of the portrait commissions. He also arranged an exhibition of her work (Bowen had brought a selection of pictures from Paris). Her portrait of Guthrie (done a few years earlier in Paris) has the same architectural layering of paint as the Sitwell portrait and the same muted palette. One of Bowens most arresting and engaging portraits, it is obviously painted with a great deal of affection the pose is casual and quite relaxed. Her insight into the character of her subjects is evident.

Bowen returned to Paris with funds to last until almost the end of the year, but by the beginning of 1933 she realised she could no longer afford to remain in her beloved France. With her apartments leased, she departed for London on her fortieth birthday. This next period of her life continued to be as peripatetic as ever. With the generous assistance of friends, she found places to rent and struggled to support herself and Julia through portrait commissions resulting from recommendations.

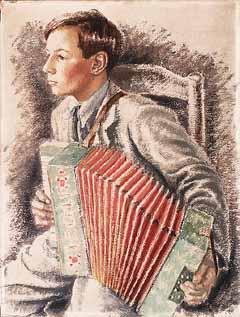

While in America, Bowen had discovered that painting childrens portraits, although demanding, was lucrative, and she decided to pursue this in England. She developed a technique for producing oil sketches on cardboard that could be completed in two to three days. She used her friends children as subjects to perfect her skills. Her portraits John Postgate 1934 and Raymond Postgate c.1934 reveal the return to this more spontaneous way of painting. The technique helped her to achieve a likeness with few sittings, particularly useful during the war period when her subjects were only available for short periods. This can be seen in Group Captain Hughie Edwards 1944 and Private, Gowrie House 1945. In these lively and unconstrained paintings, she concentrated on the facial features, only alluding to the uniforms.

John Postgate painted in Hampstead, London, 1934 oil on cardboard 74.7 x 57.2 cm private collection

In 1934, Bowen found herself briefly with a regular income when Aylmer Vallance, Phyllis Reids second husband and editor of the News Chronicle, offered her the position of art critic. She wrote reviews of exhibitions as well as pieces about homes and interior decoration until 1936, when a new editor dismissed her.

Julia wrote to her father: the only event of importance lately has been that my mother has lost her job as critic, so that God only knows where the next meal comes from, but that, however, is quite an ordinary state of affairs. 32 In October 1936 Bowen held an exhibition of her work at University College, Oxford, where G.D.H.Cole was a Fellow. Unfortunately, no list exists of the works displayed.

In August 1936, after a turbulent year, Bowen left for Cagnes-sur-Mer in the south of France to visit her friend Ruth Harris. Harris had arranged a studio for six weeks where she planned to write a book and where Bowen could paint. There are four beautiful paintings from this period. The portrait Tusnelda 1936 shows the owner of the studio with ravishing red hair and her features framed by the scene through the window and with the contrasting green of her scarf and dress. Tusnelda s interior 1936 shows the rustic, colourful studio itself. For these works, Bowen returned to a more colourful palette, evoking a sense of warmth and friendship. Her most engaging and painterly work completed during this idyllic working holiday is Provençal conversation 1936. The overhanging trees enclose the group of four sitting round a circular table. Here the surface is lively, an effect accentuated by rapid painting. The colours are high key and there are no shadows. The layering of paint and a diffused light effect create a relaxed atmosphere. The work encapsulates all the elements that were so important to Bowen: friendship, warmth, and conversation. A smaller work, White steps 1936, with its predominance of white, is enlivened by the green foliage and feathery leaves.

As war loomed in Europe, Bowen continued to live a hand-to-mouth existence. Ford had signed his British royalties over to her and she spent her years in London negotiating the sale of his books to publishers. Julia, who was now studying design at Michael St Deniss London Theatre School, wrote to Ford: These royalties have been just about saving our lives because Stella has had a very bad year for painting.33 Her father had still not completely recovered from the heart attack he had suffered the previous year. Just a year later, Julia was called to his side in France by Janice Biala; she saw him only weeks before he died on 26 June 1939.

Art And War

Wars purpose was destruction, which appeared to be the opposite of our function as would-be artists, or as women.34

Foreseeing the approach of war, Bowen and Julia moved to a cottage at Green End in Essex in the summer of 1939. Because the cottage was on the flight path to London, Bowen could afford the modest rent. When living in London, Bowen had pined for a garden with flowers and at Green End she created one resplendent with blooming hollyhocks and leafy trees.

It was at Green End that Bowen painted Julia c.1940. Eschewing the sketchy style she adopted for her portrait commissions, she returned in this work to the approach she had adopted earlier under the Italian influence. She used an informal pose depicting an angelic-faced, rosy-cheeked young woman averting her eyes from the viewer. The clothes are sombre, as it is wartime, but the decorative and curved elements are played out in the curly hair and the collars of the shirt and jacket. The background is rendered in hues of soft blue and pink.

Surviving as an artist during the war proved extremely difficult. She published her autobiography, Drawn from life, in 1941 and supplemented her meagre income through teaching art work she found tedious and unrewarding. Through a brief but challenging stint as a broadcaster with the BBC, she met Theaden Hancock, their Talks Director, with whom she became close friends. But when the Australian High Commission in London approached her on behalf of the Australian War Memorial about becoming an official war artist, Bowens life took a new artistic course. Her appointment in February 1944 was both an honour and a financial relief, since it provided her with a steady income until 1946. Wearing a womens army uniform with the rank of honorary captain, she travelled to military establishments across England. She established a studio in Danvers Street, Chelsea, where, despite the intensive bombing raids, she completed her paintings for the Memorial.

Bowen was ready to take on the challenge of painting war subjects. Over the course of her life she had been building a repertoire of painting techniques that she could now draw on. She loved drawing and it continued to underpin her work. And she still enjoyed painting groups; for years she had yearned to paint a large group of people treated as purely formal decoration.35 Confident in portraiture, she could now adopt either her slow, detailed painting technique, or call on the sketchy, dry-paint style she had mastered, to create a likeness of her subjects.

Her experience in 1944 at the RAF station at Binbrook, painting the portrait of the bomber crew who never returned, was an emotional initiation into war subjects. In D-Day, 0300 hours, interrogation hut 1944 45, she used a theatrical device, a stage set within a stage. Bowen created the tense and hushed atmosphere by positioning two figures in the foreground, staring quietly into the distance. She devised the composition so the eyes of the viewer are directed first to the airmen inscribing the names of the returning crews, and then into the inner sanctum, where in front of a large map, the returned crews are being debriefed.

In Wales, painting the Sunderland crews who patrolled the English Channel at low altitude, Bowen was able to marry her love of portraiture with the painting of the English landscape. She faithfully reproduced two studies Flying Officer Frederick Syme, Sunderland Captain 1945 and Pilot Officer Ronald Warfield 1945 in the strangely peaceful A Sunderland crew comes ashore at Pembroke Dock 1945.

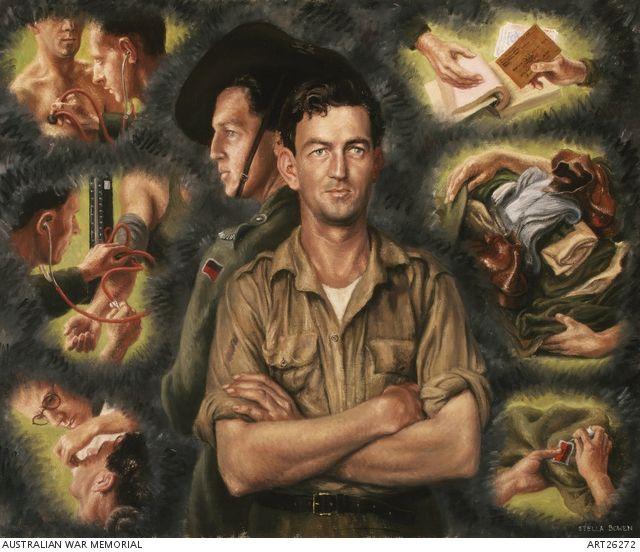

In the last stages of the war, Bowen was assigned to Gowrie House in Eastbourne, Sussex, where Australian servicemen who had been prisoners of war in Germany were debriefed, given medical examinations, and issued with new uniforms. Bowen painted Repatriated prisoner of war is processed 1945 using an unusual composition that may have had its genesis in a series of frescoes by Fra Angelico in Florence. Bowens painting resembles this artists The nine stages of prayer in its use of gesture.

Repatriated prisoner of war is processed

painted in London, 1945

oil on canvas 76.4 x 92 cm

signed l.r., oil “Stella Bowen”, not dated

Australian War Memorial

acquired under official war art scheme, 1945

ART26272

During her twenty months as a war artist, she completed forty-six paintings and drawings for the Memorial. This was fewer works than many other war artists, but Bowens method of painting was more painstaking. Overall, Bowen can be ranked with the top five official war artists appointed. Of the other four, Sali Herman painted fewer works, as did William Dobell, Donald Friend worked mainly in pen and ink, and while Ivor Hele completed a larger body of work, he was employed for a longer period. Looking back on the appointment, Bowens positive view of the opportunity it afforded is evident: This job has been a great experience, & I wouldnt have missed it for anything. It has taken me into a world that civilians usually dont get a glimpse of.36

In the spring of 1946 Bowen painted her friend Theaden Hancock in Theaden in Kensington. The portrait is a gentle rendition of a well-loved person. The diffused light and the open window looking onto the garden is Bowen at her best. The layering of paint to create texture and the fine detailed painting make this an engaging work. An interviewer for the Melbourne Herald visited her while she was doing the portrait and offered this description of Bowen: With crisply-dressed grey hair, laughing brown eyes and a round sun-tanned face, the artist is young looking and vivacious.37 Yet within months, she was diagnosed with cancer. She had earlier sought unsuccessfully to be repatriated to Australia. Members of her family offered to pay her fare and she even planned an exhibition back home, but none of this eventuated as ill-health took its toll. Theaden and Keith Hancock commissioned her to undertake her last, unfinished work, [Flowers in a green Norwegian pot]1947. Her grandson, Julian, was born three weeks before her death on 30 October 1947. (Julia had met and married Roland Loewe during the war. After Bowens death, they moved to America.)

Bowens evolution as an artist was achieved through determination and courage. She embraced the opportunities that life offered, both personal and professional, and though at times overwhelmed by the seemingly endless difficulties that confronted her, she forged ahead, refusing to succumb to negativity and passivity. At times her lack of self-confidence became a source of anxiety, but at such times Ford and her friends reassured her that she had the talent to succeed. During the crucial years in Paris, she was surrounded by innumerable artists seeking new forms of artistic expression. Through her friendship with Gertrude Stein, an avid collector and supporter of modern art, she was introduced to the work of Picasso and many of his contemporaries. Yet Bowens artistic vision remained individual and personal, with her preference for the figurative, and particularly for portraiture and interiors.

In Paris, Bowen and Ford frequented the exuberant and noisy restaurants and cafés, organised a regular bal musette on Friday evenings, and held wild studio parties. But Bowen chose not to paint these aspects of her life, preferring instead to capture its tranquil aspects, perhaps as a way of creating a sense of stability for herself, Ford and Julia. This desire to establish a home, so important to her psyche and driven yet also thwarted by the constant lack of funds, remained with her always.

Bowens legacy is a body of work (still largely unrecognised, and perhaps undiscovered) which traces an artistic growth that remained constant and personal. Bowen refused to be absorbed by the prevailing artistic isms; she was determined to retain her integrity and follow her own path.

In Search Of Stella

The works contained in Stella Bowen: Art, Love & War reveal for the first time the true extent of Stella Bowens achievement. Some of the pieces on display, while they could not be described as lost, have lain more or less hidden, either in private collections or at various institutions.

The development of an exhibition using works of art outside an institutions existing collection is always a challenging project. This one is the result of extensive research undertaken over several years and across three continents. Searching for works held in private collections is always difficult and finding individuals, who may or may not own a particular painting, is often a combination of dogged detective work and sheer good luck.

Two examples, drawn from many, will give a flavour of the hunt. The hitherto unsuspected existence of a second self-portrait of Bowen only came to light after an internet search threw up the name of the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College in the United States. This institution was aware of what it held, but apparently and understandably knew little more about this relatively unknown artist than her name. In Britain a search of Whos who for the names of all the people that Bowen might have known threw up many leads. In most cases, we were able to contact their children (or other surviving relatives) and, in this way, up to ten works came to light. Over half a dozen works were uncovered just through contacting John and Oliver Postgate and Humphrey Cole.

This exhibition is a major, but only the first, step in the journey of rediscovering the work of an artist whose war work may inadvertently have served to obscure the long process of artistic development that enabled her to create the works for which she is known.

Lola Wilkins

Head of Art

Australian War Memorial

Notes

- This was Stellas favourite quotation from the 1930s, recorded in one of her letters (Stella Bowen to Tom Bowen,19 November 1930).

- Stella Bowen, Drawn from life, Maidstone, 1974. The quoted text is in the (unpaginated) epilogue by Julia Loewe.

- Stella Bowen to Tom Bowen, 27 September 1944 (private papers)

- Bowen, p.147

- Bowen, p.36

- Bowen, p.44

- Bowen, p.35

- Bowen, p.160

- Ford had enlisted in the army but, after experiencing heavy shelling in France, was deemed unfit to return to the front and placed in command of the 23rd Kings Liverpool Regiment.

- Ford Madox Ford to Herbert Read, 2 September 1919, in Richard M.Ludwig (ed.), Letters of Ford Madox Ford, Princeton, NJ, 1965, p.98

- Usually known as Julia, she is often referred to as Julie, both by her mother and others. Indeed, in the epilogue Julia contributed to the 1974 edition of Drawn from life, she refers to herself in the third person as Julie.

- Bowen, p.82

- I date this portrait c.1920 based on the style, which is clearly influenced by the teachings of Walter Sickert, and the use of an English canvas and stretcher. Joseph Wiesenfarth disagrees with this date; see below, p.37, n.29.

- Ford Madox Ford, It was the nightingale, New York, 1975, p.155

- Ford Madox Ford to Anthony Bertram, 20 January 1923, in Ludwig, pp.14748

- Bowen, p.100

- Bowen, pp.9697

- Ford Madox Ford to Stella Bowen, 7 May 1923, in Sondra J. Stang & Karen Cochran (eds.), The correspondence of Ford Madox Ford and Stella Bowen, Bloomington, Ind., 1993, p.196

- Cathy Hueffer to Frank Sokice, 4 February 1924, in Max Saunders, Ford Madox Ford: a dual life, vol.2, Oxford & New York, 1996, p.145

- Bowen, p.166

- Nationale des Beaux-Arts, 1 May 31 August 1925, no.53

- Bowen, p.134

- This painting is also known, variously, as Au Nègre de Toulouse and Tryptych .

- Bowen, p.174

- Sisley Huddleston, Bohemian literary and social life in Paris: salons, cafés, studios, London, 1928, p.139

- Ford to Bowen, 17 October 1927, in Stang & Cochran, p.334

- Bowen used the device of a rear mirror in a number of her portraits, particularly of her women friends. A common device in the art of the 1920s, it adds an extra dimension to the works.

- Bowen, p.188

- Bowen exhibited 25 paintings at an exhibition of her work at Galerie Barreiro, Paris, 15 29 May 1931.

- Bowen, p.193

- Stella Bowen to Kathleen Kyffin Thomas, 15 July 1932 (private papers)

- Julia Ford to Ford Madox Ford, 8 April 1936, in Stang & Cochran, p.446

- Julia Ford to Ford Madox Ford, Summer 1938, in Stang & Cochran, p.456

- Bowen, p.63

- Bowen, p.231

- Stella Bowen to Tom Bowen, 27 September 1944 (private papers)

- Melbourne Herald, 1 May 1946

Funding for this exhibiton is provided by the Minister for Veterans’ Affairs commemorations program.