1918: Australians in France - Nurses - "The roses of No Man's Land"

- 1918: Australians in France

- Nurses

Nurses were the most significant section of the group of Australian women that participated in the war effort away from the home front. As part of the Australian Army Nursing Service, 2,139 Australian nurses served in the First World War, and 130 worked as part of the British nursing service. Female doctors were not permitted to join the medical services, because it was thought women would be too "delicate" for war medical work. Yet horror and heartbreak was what nurses faced every day in this war, and their vital work earned them a new respect within the medical profession.

Sister Pearl Corkhill was one of the few Australian Nursing sisters to receive the Military Medal. She had been transferred to No. 38 Casualty Clearing Station, which twice suffered heavy German air raids during the week of 27 July. One bomb wrecked the sterilising room and others fell within the camp. Corkhill was on night duty at the time. She wrote to her mother on 29 July 1918:

Today word came that I had been awarded the MM. Well the C.O. sent over a bottle of champagne and they all drank my health and now the medical officers are giving me a dinner in honour of the event. I can't see what I've done to deserve it but the part I don't like is having to face old George and Mary to get the medal. It will cost me a new mess dress, but I suppose I should not grumble at that- I'm still wearing the one I left Australia in.

Whereas before the First World War, Australian military nurses had been seen mostly as glorified first aid workers, by the war's end, it was clear that their contribution had been not only competent, but crucial to the war effort. Four years had seen an evolution of increasingly complex roles, and nurses' positions as medical workers diversified and strengthened.

Nurses became an integrated part of split-second treatment decisions. They were indispensable team members in the ever-busy operating theatres, as well as keeping entire hospital operations running smoothly. By 1917, some were even transferred to casualty clearing stations- the first point of entry for wounded from the front- a real measure of how much attitudes towards nurses had changed.

Nurses had a unique role in the war. On the one hand, they were busy cleaning wounds, sometimes even performing minor surgery, administering treatments and frequently doing heavy physical labour, often living in squalid conditions, in trying climatic environments. They were usually understaffed and lacking supplies, sometimes under threat of attack, and constantly fighting off exhaustion and sickness themselves. On the other hand, they were also expected to be feminine, cheerful, and a sweetheart and mother to every patient- the physical substitute for all the women back home.

Men often mentioned the kindness and outstanding work of nurses in their letters home. In a hospital in England, Private John Hardie wrote to his mother:

I would never have got across here if it hadn't been for one of the nurses in our ward, who was an Australian. She used to do her best to get all the Aussies across. There seems to be a great difference between our nurses and the British nurses. Of course they are all very kind, but I would rather be in an Australian hospital at any time.

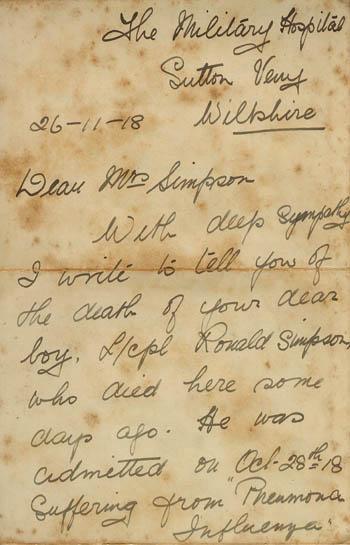

Patients and nurses often became friends, and nurses frequently wrote to the families of those men who died while under their care. When Private Ronald Simpson died, a nurse wrote to his mother expressing her sorrow, and also enclosing a lock of his hair.

A nurse assisting in an operation at the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station in November 1917

A cartoon drawn by a patient in an autograph book believed to belong to Sister D. Wright-Hay, an Australian nurse.

Sheet music for the song The Rose of No-Man's Land which praises Red Cross nurses

The first page of the nurse's condolence letter to Mrs Simpson