The Raws Brothers

Serving as lieutenants in the 2nd Division, brothers John Alexander “Alec” and Robert Goldthorpe “Goldy” Raws both experienced the horrors of Pozières. In 1927 the Australian War Memorial received copies of their letters, penned between 1915 and 1916. Their father, Reverend John Garrard Raws, was uncertain that the letters were of any value, but those belonging to Alec Raws came to be regarded as “some of the most honest, insightful and horribly graphic accounts of the experiences of Pozières”.

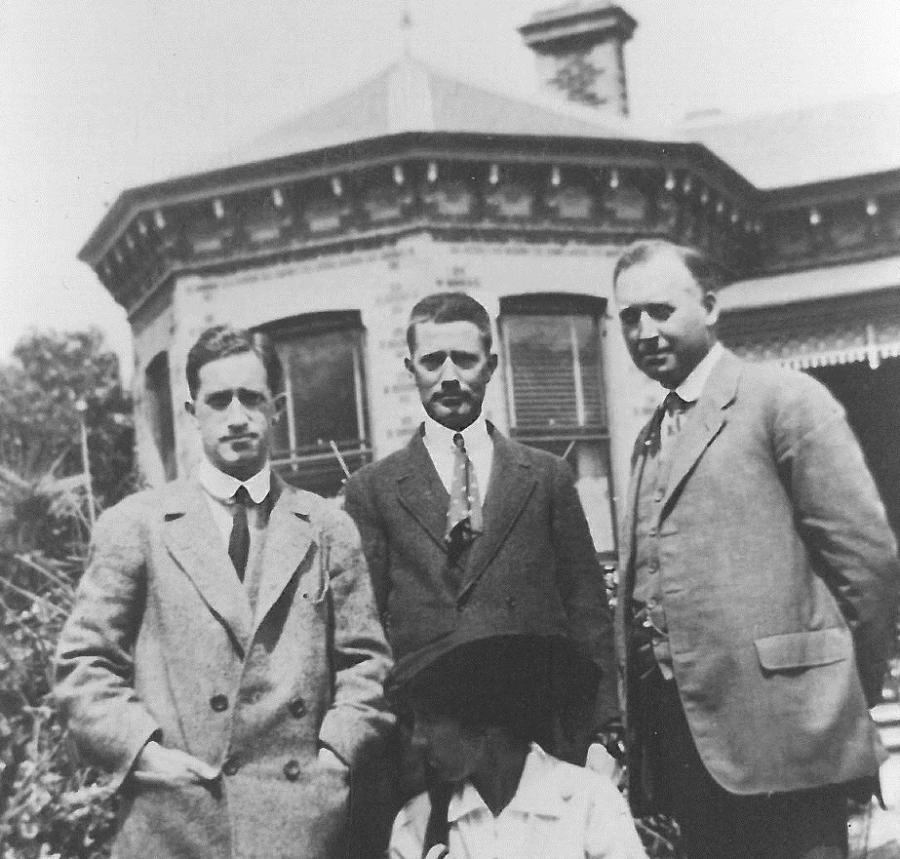

Brothers John Alexander and Robert Goldthorpe Raws. Photograph reproduced with permission of Rene White nee Raws.

Having emigrated from England in 1895, the Raws family settled in Adelaide before moving to Melbourne. The family comprised three boys, Alec, Goldthorpe, and Lennon, and sisters Helen and Gwen. Goldy Raws was the first to sign up in January 1915 after returning to Melbourne from work at a Queensland sugar plantation. He sailed to Egypt with the 23rd Battalion, where he wrote about his training, the sights, donkey racing, and unseemly behaviour among some of the men. He was sent to Gallipoli in September 1915, and reported that the men there were generally happy, and that things were exciting. He described the death and destruction around him in a letter dated 4 December 1915, adding that sometimes he was as “near as Hell as I ever want to see”.

The Raws family. Photograph reproduced with permission of Rene White nee Raws.

Raws arrived on the Western Front on 29 March 1916. On 23 June he wrote, “Last night, to give an extra interest to the night’s performance, the Huns sent over gas.” In the same letter he added his conviction that the war would be over soon. As the days progressed, however, he complained of a continuous headache from the noise, and shared his worries about his brother Alec joining him at the firing line: “There has been enough blood spilt to blot out all the maps that have ever been drawn in the world.” Lieutenant Goldthorpe Raws, 9 July 1916.

By the time Goldy Raws was fighting in France, his older brother Alec was making his way to Egypt. Despite his small stature and frail health, Alec Raws was a talented sportsman, and in his youth had played cricket and tennis. Despite his father’s disapproval, he went into journalism, holding various jobs in Perth and Adelaide before settling in Melbourne. When the war broke out, Alec Raws declared his hatred for the idea of the blood, cruelty, and suffering that war could bring, and was angry towards the government for letting it happen. However, he felt a strong sense of duty to his friends and brother already serving, and believed that “the only hope for the salvation of the world is a speedy victory for the allies”.

Raws’s initial application for enlistment was rejected, as he did not meet the height and chest measurement standards of the time, but these restrictions were later relaxed, and he was eventually accepted on 12 July 1915.

Raws was keen to do a good job, and even practiced sleeping on the floor prior to embarkation. However, the erosion of his enthusiasm is evident in his letters home. On 12 May 1916 Raws wrote about his disappointment in a military career in Egypt, where there was no fighting, people were irritable, the heat was terrible, and there wasn’t much to do. On 19 May he departed with his battalion for France, hoping to finally meet up with his brother. At this point he described the military as having “the worst organisation that one can experience”.

After spending much of June behind the firing lines, Alec Raws wrote about his desire to make it in to battle. He also complained about people taking “soft jobs” to avoid being at the front: “God forgive them … for we will not …Though they are not as bad as the ones who never left Australia.” He finally made it in to battle in July, where he described the shaking ground, the belching guns, the wet, the cold, the people being blown to pieces, and the “absurdity of war” with little hope of anything better “for tomorrow, the day after, or the year after”.

The brothers never did meet up. Goldthorpe Raws went missing in action in July 1916. Alec had by this time transferred to the 23rd Battalion, arriving on the same ground as his brother on the day he went missing. Mixed reports stated variously that Goldthorpe Raws had been killed in a charge as he left the trenches, had been blown to pieces by a shell, or was simply wounded. Alec Raws searched the battlefields in vain for his brother, and by mid-August had accepted that he had likely been killed in action.

Both Alec and Goldthorpe Raws wrote letters to each other throughout the war, and to their family. After his brother’s death Alec Raws wrote home regularly, with increasingly graphic detail about what he was witnessing:

We are lousy, stinking, ragged, unshaven and sleepless. Even when we’re back a bit we can’t sleep for our own guns. I have one puttee, a dead man’s helmet, another dead man’s gas protector, a dead man’s bayonet. My tunic is rotten with other men’s blood, and partly splattered with a comrade’s brains. It is horrible, but why should you people at home not know? Several of my friends are raving mad. I met three officers out in No Man’s Land the other night, all rambling and mad. Poor Devils!

To illustrate the conditions on the Western Front, on 9 August John Raws wrote that the Gallipoli veterans would rather have had another month on Gallipoli than one more day of the “great push” in France.

On 19 August Raws wrote to his remaining brother, Lennon, stating his belief that their brother had in fact been killed not by the hands of the enemy but through the “incompetence, callousness, and personal vanity of those high in authority”. This was to be his last letter home, as he was killed in action on 23 August 1916, aged 33. He was reportedly killed by artillery fire, although this was never formally confirmed. Neither Alec’s nor his brother’s body was recovered from the battlefield.

The Raws brothers are remembered on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial to the Missing, and on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Reverend and Mrs Raws first heard about Goldthorpe’s death on 29 August 1916 – the date of their wedding anniversary. News of Alec’s death reached them on 21 September 1916 – his birthday.

It is estimated that the 23rd Battalion lost an estimated 90 per cent of its original members in the fighting around Pozières in July and August 1916.

Questions and activities

-

Read Lieutenant Goldthorpe Raws’s letter dated 10 September 1915.

-

Was he more afraid of shells or bullets? Why?

-

Raws writes about swimming with his platoon. What other activities do you think Australians participated in when they were not on duty on Gallipoli?

-

-

Read Goldthorpe Raws’s letter to his nephew, dated 2 October 1915.

-

What did he compare bombing to?

-

His description of the death of a man could be considered impassive. Why do you think he wrote in this way?

-

-

Read Second Lieutenant Alexander Raws’s letter dated 20 July 1916.

-

Make two lists, one summarising the aspects of war which Raws was enjoying, and in the other the aspects which he complained about.

-

If Raws had known about the positives and negatives of war as described above, do you think this would have changed his decision to enlist? Why or why not?

-

-

In Alec Raws’s letter dated 4 August 1916 he wrote: “If the body lives, the brain must go forever.”

-

What do you think was meant by this statement?

-