Ingenuity at a Prisoner of War Camp: Arthur Purdon and the Changi Artificial Limb Factory

After the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Changi became home to some 15,000 Australian prisoners of war. Internees of Changi displayed ingenuity and resourcefulness during their imprisonment, establishing facilities including a prison library, a university, soap factory, rubber factory, pottery manufacture and broom manufacture. Also established within the prison camp was an artificial limb factory, the result of Arthur Henry Mason Purdon’s hard work and motivation.

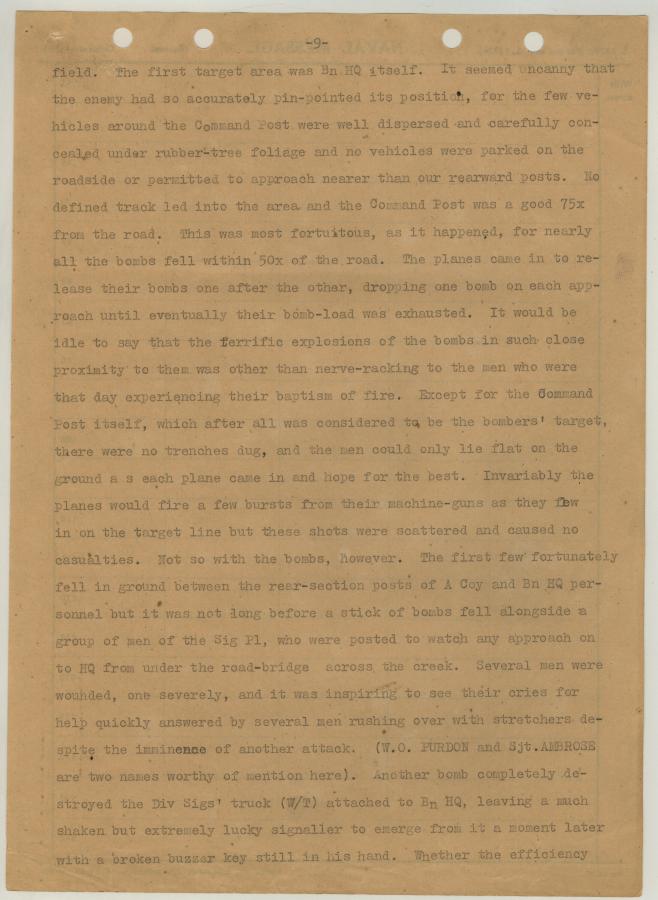

Arthur Purdon was born in Sydney in 1900 and served as a member of the 2/30th Battalion. He was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his bravery during an overwhelming Japanese attack in the Gemas area on 16 January 1942. The last person to leave the battlefield, Purdon remained in danger to assist wounded men, while being subjected to enemy fire.

2/30th Battalion War Diary entry noting Purdon’s actions at Gemas, RCDIG1027059 [pg. 65]

Before the war, Arthur Purdon worked as a health inspector. His experience gave him the skills to establish the artificial limb factory. The factory was born out of necessity; due to disease within the camp, amputations took place. The factory was established alongside the convalescent depot building, which was used for rehabilitation of individuals who had lost limbs.

Selarang Barracks compound where the prisoners of war were housed; the convalescent depot is in the right middle distance.

Murray Griffin, Selerang AIF PW area, 1943, brush and brown ink and wash over pencil on paper, ART26512.

Purdon’s factory was resourceful. Materials and tools were improvised using scrap metals from Japanese dumps and repurposed items; a drilling machine was made using the ironwork of a stretcher, a jigsaw was powered by a refrigerator motor, and some artificial feet were made from spruce from a billiard table. Other materials repurposed for use as part of artificial limbs included bolts from cars, aluminium from kettles, and split angle iron from steel cupboards.

Murray Griffin, Artificial Limb Factory, Changi, 1943, brush and brown ink and wash over pencil on paper, ART26503.

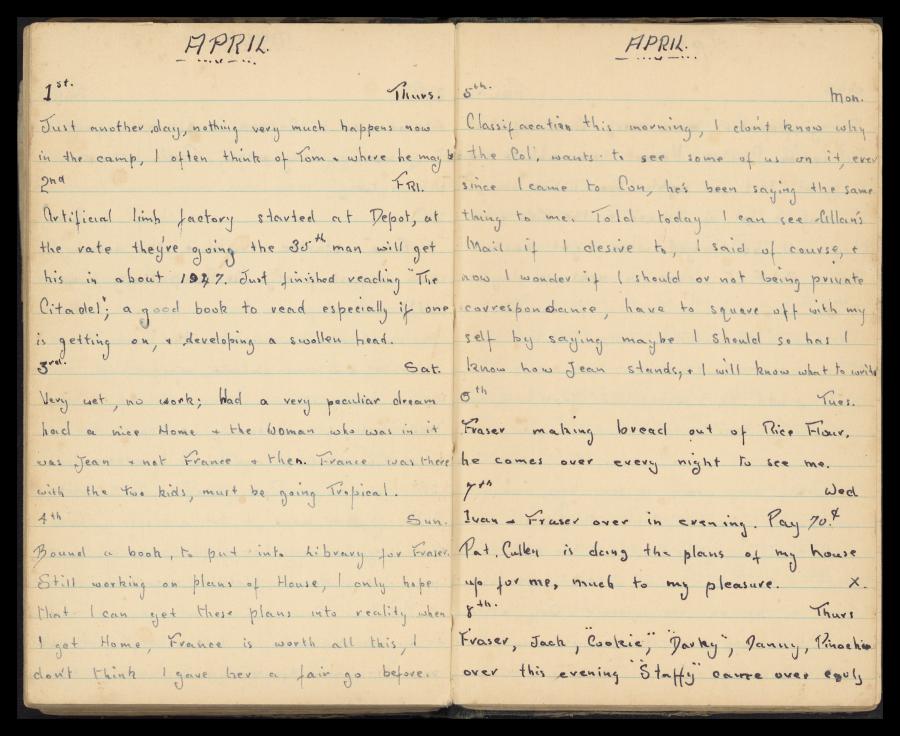

As described in the diary of Private Francis Russell James Day, a fellow Changi internee, the factory began slowly. Day described its beginnings on 2 April 1943, stating that “at the rate they’re going the 35th man will get his in about 1947”.

Diary of Francis Russell James Day, noting the establishment of the artificial limb factory. AWM2021.7.17 [PG.161].

While Purdon and his comrades faced some initial struggles, trial and error allowed them to perfect and refine their manufacturing techniques. During his factory work, Purdon invented the Purdon Joint, designed to allow limbs to move similarly to a normal leg. Practical use of the artificial limbs was monitored. The use of a limb started at one hour a day, allowing the stump on the amputated limb to harden, with practice allowing the wearer to eventually walk naturally, without the aid of a walking stick.

Men at Changi Prison Camp wearing artificial limbs made in Purdon’s factory, 1945. Photographer unknown. AWM019327

Prisoners of war missing limbs came together for rehabilitation at the convalescent depot, which focused on improving capabilities and healing. Sports such as golf, cricket, basketball, volleyball and tennis were a popular form of rehabilitation. When it was discovered that falls caused pain in the amputated limbs of individuals, a warrant officer who knew ju-jitsu, set about training his peers to fall in a safer manner.

Men play deck golf at the convalescent depot.

Murray Griffin, Battle casualties, Malaya, 1943, brush and brown ink and wash over pencil on paper, ART25088.

Individuals with amputations above the knee often had trouble adapting to the artificial limbs, which were longer and heavier to wear. A daily parade was established to encourage those who struggled to practice wearing their artificial limbs without crutches.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Webster of the Australian Army Medical Corps noted, “the force here and the limbless are very much indebted to … Purdon. He has been most practical, ingenious and arduous in his untiring energies at all times, never sparing himself in the problems to be worked out.”

The digitised diaries of the 2/30th Battalion, with details of Purdon’s bravery at Gemas, as well as those of Private Francis Russell James Day and Lieutenant Colonel Robert M.W. Webster, offer a fascinating insight into the artificial limb factory.